Creating a new chapter for World Heritage Site, Caernarfon Castle

Castles have long been one of the most intriguing parts of our built heritage. Originally designed to deter and defend against invaders, today, many of them exist as major tourist attractions, often welcoming hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. Whilst these structures offer a fascinating insight into our past, they can often pose a number of limitations to visitors – with narrow access corridors, winding spiral staircases and worn treads making them inaccessible to many. As such, the need to conserve and enhance their significance is tremendous, as is the need for them to adapt to accommodate all visitors – enabling the widest possible range of people to explore, enjoy and understand these important parts of our history.

Since 2016, Buttress has been working with Cadw on a landmark project to redevelop the King’s Gate at Caernarfon Castle. Recognised internationally as one of the greatest structures of the Middle Ages, the castle is Grade I listed and a designated Scheduled Monument, becoming a part of Wales’ first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986. Our brief was to make a larger section of the upper battlements accessible to all, to improve interpretation of the site, and to create new visitor facilities including a caf provision and lookout, offering some of the best views across North Wales.

It was important to maintain the charm and historic significance of the castle whilst also providing usable spaces and incorporating interventions that are both reversible and non-intrusive. Our plans have added a new layer of architecture to the medieval building through the creation of a lightweight structure that sits on top of and within the triple-towered King’s Gate. On the upper levels, this structure spans the King’s Gate, providing seating areas offering views across the castle complex and beyond.

Contents |

[edit] Improving accessibility

Achieving improved access to the site has resulted in a new lift within the King’s Gate; the first intervention of its kind within a UK World Heritage site. The passenger lift is located within Tower 1 and provides access from ground level, perforating the viewing platform with glazing to all four sides.

Balustrading is frameless to the outer perimeter of the platform with concealed fixing plates, capped with a bespoke deep profiled timber handrail with an inset flush metal strip, providing the opportunity to pause and gaze out across the castle grounds.

The platform walkways, elements and components have been designed to sit below the ‘as existing’ wall head height, giving the illusion of the glazing extending from the stone wall heads.

[edit] Adding a new layer of architecture

Our approach respects the fact that the King’s Gate was left as incomplete, recognising that this is part of the outstanding universal value of the World Heritage site. As such, our designs have not sought to complete the building, but simply add another layer to its history. All new interventions have been designed to be visually and physically separate from the castle walls, only lightly touching the building at access points.

This approach has also been applied to the way in which we introduce furniture into the spaces. The majority has been prefabricated off-site, brought in and slotted into place. Other pieces have been handmade and built to fit around walls or other areas of the existing fabric.

The new elements are sympathetic to the original fabric whilst being legible as modern, with a palette of materials that sit in harmony with the limestone and granite blocks. Sustainably sourced timber will be left to patina and colour naturally over time, whilst large expanses of frameless glass allow views and vistas to be maximised, unrestricted by physical posts and framing members. All glazing has been specified with low reflexivity glazing to minimise the visual impact on the monument and reduce distortion which can be found with standard glass.

Two large-glazed floor panels have been sunken into the viewing platform to provide increased daylighting into the chapel space below. The glazing has been uniquely etched with a bespoke pattern and provides a degree of privacy whilst also providing a slip-resistant surface.

[edit] No direct fixings

Similarly, mechanical fixings through the fabric have been kept to an absolute minimum to both limit scarring and to allow for the creative reuse of the existing mass. Former ledges and joist pockets were reused to restrain structural elements and take vertical loadings. New steel ring beams were fabricated to follow the skewed octagonal plan form across Towers 1 and 2 and were designed to sit upon existing stone ledges. The steel structure of Tower 3 required more careful consideration, with a concealed interwoven web of steelwork installed upon the existing undulating wall head.

No new openings or penetrations were formed within the King’s Gate. Wherever possible, the existing footprint, door openings and staircases have been reused. This can be seen in Tower 3, where the remnants of a stone spiral staircase have been revitalised and brought back into use with the introduction of a new, highly bespoke timber spiral staircase as an extension to the existing, which sits upon the original stone newel post. The staircase has been constructed from a high-performance modified wood, which is extremely durable and sustainably sourced.

In order to minimise framing materials and obscuring architectural features, large bespoke structural glass sheets have also been installed within the existing window apertures internally. The glazing follows the outline of the window openings, offset to the perimeter to encourage cross-ventilation across the interior. The windows were designed to provide a safe physical barrier, limit water ingress, and increase ventilation, whilst retaining existing stone mullions, transoms and tracery.

Physical fixings into the building fabric have been coordinated to align with mortar joints only, with no direct fix through facing stonework. This resulted in staggered and stepped fixings to coincide with the locations of suitably sized mortar beds. A bespoke steel fixing stake was developed after vigorous prototyping, sampling and load testing. The stake also provides some degree of tolerance to allow for in situ adjustments of glazed panel positions. In total, approximately 400 brackets have been installed throughout the King’s Gate.

All mechanical and electrical cabling and components are surface fixed across the walls and ceilings of the castle, with fixings taken into mortar joints. Malleable black armoured cabling was favoured over the use of surface fixed conduits, allowing for fixings to be tighter and less intrusive than angular conduit. Several strategically placed vertical risers allow for the transfer of services across floor levels, with the floor plates or raised access floors allowing for the network of cabling to be distributed undetected and hidden, whilst also being readily accessible through the careful placement of access panels.

[edit] Natural ventilation

During the early stages of the project, the impracticality of enveloping the exterior walls of the King’s Gate to provide a wholly watertight interior solution was agreed upon. As such, a semi-waterproof solution was developed, which involved the introduction of roofs within each of the towers. Existing wall heads remain in situ, reliant upon their sheer mass to control and mitigate water ingress, whilst interior spaces have been designed to encourage cross-ventilation maintained through existing window openings, with underfloor heating installed across the full floor plate to provide some background heating.

To supplement and encourage air flow through the interior spaces, ventilation is brought in at roof level through carefully concealed openings, masked by an array of organic timber seating. Air is drawn down mechanically and distributed across floor plates within a network of hidden ducting.

[edit] Fabric repairs

General fabric defects included loose mortar, spalled and friable masonry, fissures and fractures through mullions and transoms, soiled surfaces with carbon deposits, and a sulphate crust with localised soft vegetation growth, due in part to the castle’s proximity to the coast. The general philosophy towards fabric repairs was to retain as much of the original fabric as possible. Prior to undertaking any physical repairs, the fabric was closely assessed, and stone and fabric repair techniques were agreed upon by the designers, stone masons and conservation officer.

Carved stonework, statues and projections were closely inspected using pull and touch tests to ascertain their condition. The sections of stone that had become detached over time were gently worked free and reattached in situ using stainless steel dowels and resin, whilst delaminated or heavily spalled stones were cut out and new ones indented to match the existing in size, texture and bond. The facing stone, windowsills and ledges that were dished or prone to ponding were either carefully dressed back or filled with mortar to encourage water to flow towards the face, reducing the risk of a freeze/thaw cycle and causing stone defects.

A light conservation clean was also undertaken to reduce surface soiling alongside vegetation, with the cementitious mortar carefully raked out by skilled, experienced masons and repointed with a lime mortar following extensive sampling.

[edit] A sustainable approach

Given the castle’s designation as a World Heritage site and Scheduled Monument, the opportunity to introduce intrusive elements within accessible areas was restricted, whilst the archaeological constraints of the site limited the scope for any underground solutions. However, air source heat pumps have successfully been installed following careful consideration with Cadw. In addition, a layer of insulation has been introduced across each of the new tower roof decks as well as the installation of LEDs, linked to PIRs where practical. Materials and products have been sourced locally where available, such as stone from nearby quarries.

The result is a bold and innovative approach, yet subtle from the exterior, challenging convention whilst revealing and enhancing universal value of this remarkable place. The castle is now accessible to a wider audience for future generations to enjoy and explore.

This article appears in the AT Journal Winter issue 144 under the same title and was wrtten by Alex Scrimshaw MCIAT, CIAT-Accredited Conservationist, Senior Architectural Technologist, Buttress.

--CIAT

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Angstloch.

- Astley Castle.

- Bartizan.

- Boldt Castle, Heart Island.

- Castle.

- Castle Rushen Quarterdeck.

- Conservation of the historic environment.

- Crenellations.

- Edinburgh Castle.

- Edinburgh world heritage site valued at over 1 billion.

- Ljubljana Castle.

- Listed buildings.

- Machicolation.

- Neuschwanstein Castle.

- Nottingham Castle.

- Oxford castle.

- Palace of Westminster.

- Portcullis.

- Powis Castle.

- Putlog holes.

- Scarp.

- Scheduled monuments.

- Talus.

- Types of building.

- Windsor Castle: a thousand years of a royal palace.

- World Heritage Site.

Featured articles and news

CIOB report; a blueprint for SDGs and the built environment

Pairing the Sustainable Development Goals with projects.

Latest Build UK Building Safety Regime explainer published

Key elements in one short, now updated document.

UKGBC launch the UK Climate Resilience Roadmap

First guidance of its kind on direct climate impacts for the built environment and how it can adapt.

CLC Health, Safety and Wellbeing Strategy 2025

Launched by the Minister for Industry to look at fatalities on site, improving mental health and other issues.

One of the most impressive Victorian architects. Book review.

Common Assessment Standard now with building safety

New CAS update now includes mandatory building safety questions.

RTPI leader to become new CIOB Chief Executive Officer

Dr Victoria Hills MRTPI, FICE to take over after Caroline Gumble’s departure.

Social and affordable housing, a long term plan for delivery

The “Delivering a Decade of Renewal for Social and Affordable Housing” strategy sets out future path.

A change to adoptive architecture

Effects of global weather warming on architectural detailing, material choice and human interaction.

The proposed publicly owned and backed subsidiary of Homes England, to facilitate new homes.

How big is the problem and what can we do to mitigate the effects?

Overheating guidance and tools for building designers

A number of cool guides to help with the heat.

The UK's Modern Industrial Strategy: A 10 year plan

Previous consultation criticism, current key elements and general support with some persisting reservations.

Building Safety Regulator reforms

New roles, new staff and a new fast track service pave the way for a single construction regulator.

Architectural Technologist CPDs and Communications

CIAT CPD… and how you can do it!

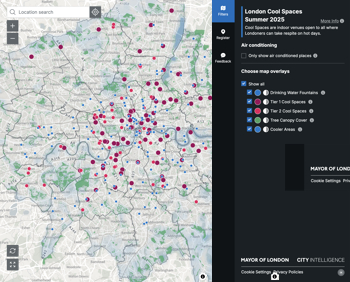

Cooling centres and cool spaces

Managing extreme heat in cities by directing the public to places for heat stress relief and water sources.

Winter gardens: A brief history and warm variations

Extending the season with glass in different forms and terms.

Restoring Great Yarmouth's Winter Gardens

Transforming one of the least sustainable constructions imaginable.