Landscape protection against terrorism

[edit] A changing security landscape

This article was originally published as 'Landscape Protection. The new front-line in the war against fear,' published by Marshalls in December 2017.

|

Since the word’s first use during the French Revolution, the concept of ‘Terrorism’ has been on an evolutionary journey. At its most fundamental, it describes the use of intentionally indiscriminate violence as a means to create terror or fear to achieve a political, religious or ideological aim. In our lifetimes, the nature of terrorism has undergone signicant change. Previously terrorists sought to make a statement - targeting high-prole, high-impact locations that would create scenes of shock & awe on the evening news and the front-pages. But attacks either side of the millennium heralded the end of terrorism as we knew it. |

[edit] A new step in terror development

| The Manchester and London Docklands truck-bombings in 1996 struck at the heart of the nation’s two biggest cities, creating wide-ranging damage to property. 9/11 in 2001 took this kind of attack to another level - for the first time putting mass murder up front and centre for a world now watching 24 hour rolling news. The one thing these attacks have in common is that they all required skills, resources, logistics, funding, planning, co-ordination, training - an organisational structure - to make them happen. 16 years on, terrorism is currently embarking on a new step in its development. |

|

In the aftermath of the Westminster attack in March 2017, the BBC’s home affairs correspondent, Dominic Casciani wrote: “The days when terrorism exclusively meant large, complex bombs and months of planning are largely gone: western security agencies - particularly MI5 and its partner agencies - are very, very good at identifying those plots and disrupting them. The longer it takes to plan such an attack, the more people who are involved, the more chances there will be for security services to learn what is going on.” (1)

Rather than face the exposure risks of managing ‘operational structures’ over an extended planning period, terror organisations now effectively ‘freelance-out’ attacks to any extremist with the inclination and a broadband connection.

Driven by developments in online communications, terrorist organisations are now recruiting, encouraging and facilitating actions by remote ‘supporters’, agitating disenfranchised individuals who only share a common (and often distorted) world view to take direct action - and then claiming credit for any outcomes. According to the recent Policy Exchange report ‘The New Netwar: Countering Extremist Terrorism Online’, an average week sees over 100 new articles, videos and newspapers produced by Isis and disseminated across a vast ecosystem of platforms, file-sharing services, websites and social media.

And the UK is an eager audience, with Britain listed as the fifth most frequent location from which content is accessed after Turkey, the US, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Indeed, the UK registered the largest number of clicks in Europe. Lead author of the report, Martyn Frampton, said: “The evidence suggests that we are not winning the war against online extremism and we need to consider options for change.” (5/6)

It’s disturbingly ironic that the advanced technology used in the conversion, motivation and recruitment of extremists contrasts so greatly with the 21st Century urban terrorist’s weapon of choice.

Dominic Casciani again: “Terrorism looks not just to kill and maim - but to create panic and such a sense of disorder that it rocks a city or nation to its foundations… (the Westminster) attacker sought to do so in as low-tech way as is possible.”(1)

Stripped down to the bare-bones of an individual with motivation, intent and access to a vehicle, attacks like this have pared down the timeline between planning and execution to a matter of hours.

[edit] Vehicles the weapon of choice

|

Vehicle-related terror attacks are on the rise. Why? Because this method of attack is “simple and, potentially, undetectable until it happens”. (1) There have been eight vehicular attacks in Europe alone in the last year - and ISIS’ media channel has warned that we can expect even more. (3) This new automotive threat has stimulated what has become a standard reaction in our cities. According to the EU Terrorism Situation and Trends report, 2017, there has been a reciprocal increase in the number of anti-terror barrier installations around city landmarks. But fortication of the public realm in this way sends mixed signals. |

Whilst concrete anti-terror barriers send a visible message that cities are taking security seriously, they also strongly imply a NEED to take security seriously - which creates doubt, raises public anxiety and actually contributes to an environment of fear. In a recent Guardian article, Simon Jenkins wrote: “Parts of central London already look cowed and afraid, as ugly barriers go up around tourist sites.” (8)

A recent poll tells us that only 15% of people say that concrete anti-terror barriers make them feel safer. 25% of respondents said barriers are an over-reaction. Most interestingly, the 48% in favour of barriers stated that this is only because they FEEL that they are essential in relation to the current terrorism threat.(2)

And it is this PERCEIVED scale of the threat that perpetuates the fear that terrorists want us to feel.

[edit] Distortion of the risk

| Whilst the battle is primarily against terrorism, those responsible for designing - and securing - our cities are fighting a secondary battle: with human nature. At its most basic level, people who are more fearful of an imminent terror attack also perceive the threat of a attack to be higher than those who are less fearful. (9) It’s a vicious circle: a higher perception of risk leads to individuals feeling as though there is a higher level of threat. And as the presence of visible anti-terror security measures have been found to increase levels of suspicion, tension and fear amongst the public (10a/b) this heightens an individual’s perception of the risk of terrorism – which leads to increased feelings of threat. It’s a reaction that is hard-wired into our brains. |

|

Anxiety worsens cognitive functioning as our attention is drawn towards to threatening stimuli such as anti-terror barriers. Individuals are then preoccupied with the source of the threat, as their attention and coping resources are drawn away from the non threatening stimuli of day to day life (11) so there is a focus on a potential threat. The outcome is inevitable: in seeking to protect public spaces, the action of fortifying our city centres actually increases fear among the public in those spaces. So how can we protect people without turning our public spaces into ‘environments of fear’?

[edit] The design challenge

|

The threat of terrorists targeting crowded public places provides urban planners and designers with a new and complex challenge. The need to create safe spaces offers those responsible for their design and protection a difficult compromise between maintaining the open, liveable nature of the public realm and the necessity for security - especially in those cities that have built global reputations on their aesthetic attraction. This dichotomy - and our attempt to address the issue thus far - does raise a fundamental question about how the inclusion of effective security will change the nature of the urban spaces we share. |

In her study ‘Invisible Security: The impact of counter terrorism on the built environment’ Rachel Briggs writes: “It has been argued that ‘security’ has become the justification for measures that threaten the core of urban social and political life - from the physical barricading of space to the social barricading of democratic activity - that rising levels of security in cities will reduce the public use of public space”. (4)

And we’d agree: what societal purpose would a fortified public space serve if it made the public feel more fearful and less social?

As terrorists have re-thought their tactics, we considered it important to re-think the way in which cities protect themselves from the growing threat of vehicular attack. How can security be more subtly integrated in the design of our public spaces? Unobtrusive, unthreatening - effectively hiding in plain sight.

That’s a subtle, but vital observation: that it’s really the people within our urban landscapes that require protection, not merely the architecture and the infrastructure.

And we placed that at the heart of our new approach to creating safer urban spaces.

[edit] A new normal - a new approach

|

As the UK’s foremost landscaping brand, Marshalls has watched the evolution of urban terrorism with interest. At the heart of our business has always been the desire to create spaces that enhance and improve the lives of those who use them. And in developing a response to the new terror threat, we have reinforced many of our core beliefs. Marshalls believe that fortification breeds a climate of fear - so we should avoid it. We know that visible anti-terror barriers heighten people’s perception of the risk and their feelings of threat. So it makes sense to create a public realm that promotes a less fearful environment. |

|

New terror tactics require new thinking on protection - and urban design must adapt to this new reality - with planners considering how to ‘design-out’ terrorism without changing how people use and feel about our city centres.

Marshalls believe that you can protect ‘soft’ assets from terrorism through landscape design - and do so in a way which is both effective, and which does not destroy the vibrancy of open, accessible city spaces.

Marshalls believe that security is not just about product specification. Marshalls think security on a human scale requires a considered approach - a landscape protection strategy that renders the environment safe by design - where the environment is created to intrinsically provide the protection people need, without an obvious show of ‘defence strength.'

Finally, we recognise the growing view among urban design experts that security features should be as unobtrusive as possible - subtly integrated into the city’s fabric.

[edit] Introducing Marshalls' landscape protection

|

Marshalls’ Landscape Protection is a new approach - a design, engineering and specification philosophy that enables highly effective protection to blend seamlessly into urban landscape design: allowing architects, planners and designers to install the highest levels of security without instilling fear. Marshalls' developments in design, manufacture and technology negate the need for bulky and obtrusive security, enabling those who design our city spaces to think more creatively about how they can include Hostile Vehicle Mitigation within landscape design features. |

[edit] Marshalls' approach

We believe that successful security should take a holistic approach. Marshalls’ Landscape Protection is based on a series of increasingly resistant interventions that Deter, Defect and Defend, a three-tier strategy designed to reduce the threat long before vehicles reach your assets.

[edit] Deter

Firstly Marshalls seeks to create ground-level design recommendations to limit the speed or mitigate the angle of approaching traffic. This can include changes in road layout, the addition of traffic-calming features and the creation of a buffer-zone that demarcates traffic from pedestrian areas.

For example, the coloured and textured surface of our deterrent paving sends a clear visual message that says “you are not permitted in this area”, without the intervention of a concrete barrier.

In identifying that you have created such a buffer-zone, you can create an immediate perception that a space is under protection.

[edit] Deflect

Secondly Marshalls can create a discrete physical segregation that denies traffic access to pedestrianised areas.

Marshalls Titan specialist vehicle high containment kerb system has been designed to prevent vehicles overrunning vulnerable areas adjacent to the carriageway. Not only does Titan provide a clear visual warning to drivers, its unique profile design redirects vehicles back onto their intended path.

[edit] Defend

Thirdly, Marshalls can create a subtle, unobtrusive defensive line that stops vehicles in their tracks.

Marshalls Landscape Furniture range allows you to implement a high level of integral Hostile Vehicle Mitigation, without compromising your aesthetic vision.

Designed around Marshalls’ ‘RhinoGuard’ technology, Marshalls' range of PAS68 / IWA-14.1 rated street furniture offers all the stopping power of a concrete barrier with none of the negative associations: capable of stopping a seven and a half tonne truck travelling at up to 50mph.

[edit] Conclusion

|

Terrorism is a worrying fact of modern life. From shopping centres and sports stadia, to rail stations, leisure venues and our high streets, any space where people gather is now considered to be at risk. But protecting those spaces is a complex balance between making people feel safe and making them feel like they’re living in a controlled, militarised environment. Marshalls believes that, in Landscape Protection, Marshalls is pioneering a paradigm shift in how architects, planners and engineers design security into the public realm. For us it’s not about putting down concrete barriers with no concern for the public mood. |

|

People deserve better spaces - and we can help you create them.

Marshalls also believe that security can be much more than simply installing heavy-duty fortification which offers little aesthetic value.

Marshalls integrated Landscape Protection approach involves the application of creative thinking, using our engineering and design know-how to create spaces that are safer by design from the outset. By incorporating our experience and expertise from a broad range of landscape design disciplines with a range of PAS/IWA-14.1 rated products in a selection of materials and finishes, Marshalls can help effectively mitigate hostile vehicular attacks without compromising the look, feel and safety of our urban environment.

Which is better for everyone.

This article was originally published as 'Landscape Protection. The new front-line in the war against fear,' published by Marshalls in December 2017.

[edit] References/sources

- (1) http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-39360710 - “London attack: What security chiefs have long been preparing for” - Dominic Casciani, Home aairs correspondent - March 2017

- (2) http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/whatnext--barbed-wire-antiterror-bollards-installedacrossmelbournes-cbd-20170622-gwwu0y.html - JUNE 23 2017

- (3) Washington Post: “Urban terrorism isn’t going to stop. Can city planners help reduce its lethal impact?” - By Jon Coaee - June 2017

- 4)‘Invisible Security: The impact of counter-terrorism on the built environment’ - Rachel Briggs - 2005

- (5) “The days when terrorism meant large, complex bombs and months of planning are gone” www.counterterrorbusiness.com/features/terrorism-trendsexplored-ifsec - 2017

- (6) www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/19/britain-has-large-audience-for-onlinejihadistpropaganda-report-says

- (7) policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-New-Netwar-1.pdf (Frampton, Fisher, Prucha 2017)

- (8) ‘Barcelona is Europe’s seventh vehicle attack in a year. What can be done?’ - Simon Jenkins, Guardian.com - Friday 18 August 2017

- (9) ‘An examination of college students' fears about terrorism and the likelihood of a terrorist attack’ - Misis/ Bush/Hendrix - 2016

- 10a) Journal of Interpersonal Violence: Perception of the Threat of Terrorism - Keren Cohen-Louck - April 2016

- (10b) University of Nebraska: ‘ Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management: Evaluating the societal response to antiterrorism measures’ - Grosskopf - 2005

- (11) ‘Threat, Anxiety, and Support of Antiterrorism Policies’ (American Journal of Political Science) Huddy/Feldman/ Taber/Lahav - May 2005

- ‘Aesthetically pleasing, crash-tested street furniture: why functional will no longer do’ - a trend report from IFSEC Global, 2016

- ’Do Terrorists Win? Rebels' Use of Terrorism and Civil War Outcomes’ Fortna - May 2015 (via Cambridge University Press Volume 69, Issue 3 Summer 2015)

- ‘The Visibility of (In)security: The Aesthetics of Planning Urban Defences Against Terrorism’ - Coaee/O’Hare/ Hawkesworth - September 2009

- ‘Studies in Cfonict & Terrorism: Terrorism, Security, and the Threat of Counterterrorism’ - Jessica Wolfendale - Oct 2005

- https://theconversation.com/westminster-attackraisesspectre-of-new-rings-of-steel-to-boost-securityinurban-centres-75036 - March 23, 2017

- www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/08/tougher-policing-wont-end-terror-attacks-britain - ‘Why it’s becoming impossible to stop the terrorists’ - Robert Verkaik - June 2017

- www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/21/us-and-them-extremism-terror-attack

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Approved document Q

- BRE National Security Survey

- Embedded security: Procuring an effective facility protective security system

- Engineering resilience to human threats

- Global overview analysis of fire and security

- Hostile architecture

- Infrastructure and cyber attacks.

- Landscape protection.

- SABRE.

- Scarp.

- Security and the built environment

- Security consultant

- Security rating scheme

- Terrorism.

--Marshalls 11:23, 30 Jan 2018 (BST)

Featured articles and news

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description fron the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

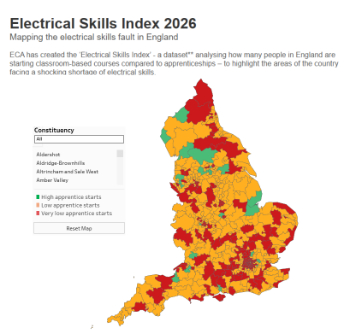

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.

Futurebuild and UK Construction Week London Unite

Creating the UK’s Built Environment Super Event and over 25 other key partnerships.

Welsh and Scottish 2026 elections

Manifestos for the built environment for upcoming same May day elections.

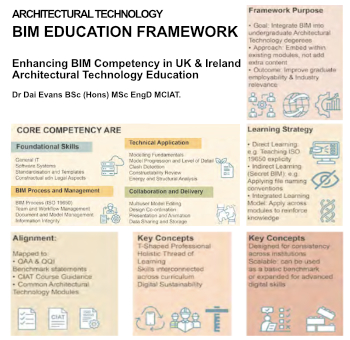

Advancing BIM education with a competency framework

“We don’t need people who can just draw in 3D. We need people who can think in data.”

Guidance notes to prepare for April ERA changes

From the Electrical Contractors' Association Employee Relations team.

Significant changes to be seen from the new ERA in 2026 and 2027, starting on 6 April 2026.

First aid in the modern workplace with St John Ambulance.

Solar panels, pitched roofs and risk of fire spread

60% increase in solar panel fires prompts tests and installation warnings.

Modernising heat networks with Heat interface unit

Why HIUs hold the key to efficiency upgrades.