Anti-bribery and Ethics - A Construction Perspective

Contents |

[edit] Aim

The purpose of this article is threefold:

- To provide a background as to why anti-bribery and ethical considerations are relevant in construction;

- To present anti-bribery measures in a process approach;

- To explain how these measures can be addressed in a quality management system.

[edit] Introduction

What is Bribery? What is Ethics, e.g. Conflict of Interest? Why is managing them important in construction?

The Collins English Dictionary [1] defines a bribe as ‘anything offered or given to gain favour’. This emphasis on influence is a wide definition which suits the purpose here to convey the potential scope of the problem.

There are many types of bribery:

- Institutional - where the organisation is complicit;

- Personal – where it is for individual gain;

- Supply-side - offering bribes;

- Demand-side – people in a position of authority demanding bribes.

It should be noted that in UK law, the Bribery Act 2010 [2] allows companies resident in the UK to be prosecuted for alleged transgressions anywhere in the world.

An important ethical consideration in the commercial world, including construction, is Conflict of Interest:

- Client conflict – e.g. where the organisation has gained knowledge on one scheme that could give it an unfair advantage in bidding for work on an associated scheme with that client.

- Personal conflict – where the individual has a vested interest in a scheme on which they are working.

Potential conflicts must be formally declared and recorded, not least to protect the organisation or individual concerned from dispute.

Unethical behaviour impacts the individual, the business (organisation) and society.

If associated with unethical activity, implications for the company are:

- Loss of reputation;

- Loss of future business, e.g.:

- Prevented from bidding for projects funded by international finance institutions (World Bank and others);

- Loss of government contracts through being proscribed.

- Significant penalties, e.g. ruinous fines and individuals may face prison sentences.

Many companies are certified to the standard ISO 9001:2015 – Quality management systems – Requirements [3] which is often sought by clients at proposal stage. This article seeks to show how important principles of that standard can be applied to anti-bribery and ethics management, e.g. the crossover between ‘interested parties’ and ‘business associates’.

Note: for those seeking certification for a dedicated anti-bribery management system, reference should also be made to the standard ISO 37001:2016 – Anti-bribery management systems – Requirements with guidance for use [4].

[edit] Anti-bribery process

ISO 9001 [3] has a chapter on the ‘Context of the organisation’ which specifies that an organisation must determine external and internal issues that are relevant to its work and expects it to monitor and review information about those issues.

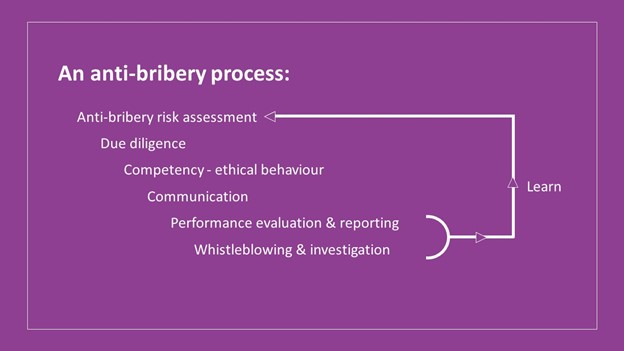

The standard also requires that the organisation determines the processes needed for its operations and requires that its leaders actively promote the process approach. The authors of this article offer here an anti-bribery process to address ethical risks which can be both external and internal.

Each of these process steps together form a framework and are described individually in turn below.

[edit] Anti-bribery risk assessment

In its ‘Leadership’ qualities, ISO 9001 [3] expects leaders to engage in ‘risk-based thinking’. Implementing this method starting before, and continuing during, the proposal stage can allow teams to identify and manage bribery risks from inception to completion.

ISO 31000:2018 – Risk management – Guidelines [5] provides a methodology for addressing risks and opportunities. It describes the need to:

- Analyse the effects of the risk (e.g. assess likelihood of risks occurring);

- Evaluate their significance (e.g. categorised as high, medium or low risk);

- Determine the level of control and actions required to manage the risk; and, of course

- Reviewing the continuing effectiveness of the actions.

In ‘Operations’, ISO 9001 [3] talks about control of externally provided processes, products and services so consideration of risk would apply to the management of the supply chain, including Subcontractors. This is also known as procurement risk or supply chain risk. An example would be a company being able to organise delivery of its equipment to site, when the goods are needed, without paying a bribe.

ISO 37001 [4] requires the risk assessment to be reviewed on a regular basis, or when there are significant changes. An example would be a change in supply chain, thus reviewing the risk assessment allows any new information to be assessed and any appropriate action to be taken as a result.

It may be useful here to talk about some of the ethical risks that firms in the construction industry can be exposed to.

A Contractor can be approached before an opportunity hits the market or public forums and other firms, such as architects, consultants and designers, can be lined up to participate or be partners. The challenge is to avoid an advantage being gained through unfair access to information.

Competency and ethical behaviour considerations extend from the recruitment process (e.g. when putting teams together, ask candidates an ethical question at interview), through the supply chain and on to scheme delivery.

Modern slavery and human trafficking are ethical issues now proscribed by law, e.g. Modern Slavery Act 2015 [6] in the UK. The construction industry is particularly vulnerable to this because of its significant use of subcontract labour. An organisation is not only required to prevent and monitor for these crimes, but also to take responsibility for the actions of its supply chain. An example of an ethical risk in this area for Contractors is the behaviour of the Subcontractors they appoint, e.g. in ensuring that good pay and conditions are offered and are compliant with the law. A formal audit may not be able to uncover wrongdoing here, so a mitigation measure may be to employ ‘Mystery Workers’ or ‘Mystery Walkers’ in the operation of concern to provide insight. Slavery and trafficking are pernicious and likely to damage the reputation of any organisation so affected or associated.

Corruption can take many forms, for example where a person in a position of authority at the client (e.g. Facilities Manager) becomes linked with the senior leadership of one or more Contractors involved. The disbenefits to the client organisation concerned could impact on its financial health and even result in legal action.

Particularly on very large infrastructure projects, the possibility of Conflict of Interest arises. For example, where people working on one scheme gain knowledge for the company that could give it an advantage when bidding for a related scheme. These people must be separated from the new bid and consideration of the conflict recorded in a register.

Special consideration must be given when dealing with companies or officials in locations where bribery or other inducements is usual and accepted as part of normal business transactions, whether these take the form of ‘Facilitation payments (to move goods) or ‘Sweeteners (to enable the award of contracts).

It is important to understand local law and customs at the outset to avoid surprises. It is also necessary to research the procedure for getting permission for your resources to work there. In some countries where bribery is endemic, it is necessary to set up measures to mitigate against this, for example, ones relating to financial controls around payments. Where there is interface with public or government officials, e.g. in obtaining approvals and permissions at stages of the works, there again needs to be transparency over the process.

To keep track of the laws pertaining in the different countries in which the organisation operates, it is necessary to have a Legal Register which shows laws applying and the subject area.

It is worth bearing in mind when assessing risks that an ethical risk may apply to a particular business sector or activity and not the whole construction industry.

Building on anti-bribery risk assessment, completing due diligence on all the parties involved (including supply chain and procurement) can provide extra knowledge to further inform decision making on whether to engage in a business relationship or project. Due diligence on third parties (e.g. supply chain, partners, affiliates and sub-contractors) is initially carried out to identify aspects such as:

- Their business ethics policies;

- Financial stability / credit checks;

- Association with sanctioned countries;

- Who is the beneficial owner of the company and are they, or any directors of that organisation, ‘Politically Exposed People’ (i.e. involved with the political establishment);

- Potential involvement in modern slavery or human trafficking;

- Qualifications, competencies and insurances.

To be effective, due diligence would need to be refreshed at defined frequencies. This could be based on the level of risk they are perceived to represent. These updates can capture and identify changes over time, providing an opportunity to review the new information, e.g. detect potential new risks of bribery. The type and degree of due diligence checks will vary and should be proportionate to the type of business and work being carried out.

Methods for due diligence include from a search of the Internet to review at a library and using specialist electronic tools in the fields of finance, ethics and human rights, e.g. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) [7].

Another element of due diligence is protecting the organisation’s interests using contract terms and conditions. Third parties can have ethics policies in place, setting out anti-bribery principles which may be referenced in the contract. Within the agreement there should be provision on expectations around ethical behaviour and conduct. Thirdly, there should be allowance for participants to have the right to terminate the contract should a third-party breach legislation, or the agreed anti-bribery management clause.

A litmus test is to ask yourself, ‘Are the duties and fees set out for each of the parties in the contract in proportion with the amount of work required of them?’.

6. Competency – ethical behaviour

However thorough, a risk assessment is only as effective as the efforts of the people who put its countermeasures into action. In other words, the behaviour of these people in the workplace must be informed by their knowledge and understanding of ethics.

The organisation should have a policy on ethics that sets out the standards of behaviour it expects from everyone, pertaining to the areas of business it is involved in. The policy must be communicated to staff and should also form the basis for awareness training.

In addition to a general Ethics Policy, many companies incorporate a specific Code of Business Conduct within their standard Human Resources policies. It, too, can be incorporated into the awareness training.

As defined by ISO 9000:2015 – Quality management systems – Fundamentals and vocabulary [8], competence is the ability to apply knowledge and skills to achieve the intended results. These can be developed from education, training and experience. Regarding ethics, teams may need to acquire knowledge through internal or external awareness training, to ensure they have the required understanding. For example, topics may include the values of the organisation, types of risk likely to be encountered, what is good ethical behaviour and how to report an incident.

In construction, issues to cover could be:

- Contractor’s personnel wrongly charging a levy that Subcontractors must pay to work on a project;

- A person at the Contractor conspiring with Subcontractors for them to receive payment for invoices for work that has not been carried out;

- Ban on facilitation payments (e.g. inducements to officials to expedite something that is already correctly contracted to be delivered);

- Avoiding offering or accepting high value and/or frequent gifts and hospitality – all gifts and/or hospitality to be registered with the employer;

- What Conflict of Interest might look like on the project?

Training delivery can use on screen and hard copy presentational material and include test questions during and/or after the course. It is usual for the training to conclude with the trainee being asked to sign a declaration that they understand the topic of ethics and will comply with the Code of Conduct.

Advanced training should be made available to people in positions of authority, those providing advice on ethical issues and individuals who might be exposed to greater bribery risks, e.g. those involved in procurement, undertaking a monitoring or supervision role or working in countries where bribery can be endemic. Having a greater depth of understanding will provide people with the right tools and knowledge to recognise and respond to ethical issues.

The senior leadership team should also receive more in-depth training and have available specialist expertise to consult, e.g. on the topic of fraud to ensure financial procedures provide an adequate defence.

As well as internal staff, subcontractors and subconsultants need to understand and apply the principles of anti-bribery management. This could be through agreeing to each other’s ethics policies, awareness training and conditions of employment. The veracity of services provided by the whole supply chain needs to be managed to trace any potential ethical risks which may arise by way of third-party association.

Raising awareness of an organisation’s ethics policy and Code of Business Conduct serves to provide protection in that it can show clearly to its employees, and any outside parties, that an ethical culture is embedded in the way it operates, and that transgressions would not be tolerated.

[edit] Communication

Defending an organisation’s ethical reputation begins with the pillar of everyone in that organisation having a good understanding of what the threats are and how to behave if faced with them.

ISO 9001 [3] expects leaders to communicate the quality policy and promote awareness. In this case, as it relates to anti-bribery or ethics policy. The direction of communication must be twofold: internal and external to the organisation.

Raising awareness is crucial internally; begin by communicating the policy and how it concerns the construction business. The audience should be every member of the organisation (including Subconsultants and Subcontractors) and thought needs to be given to how to reach them all (communication media), e.g. at Toolbox Talks, via the Intranet, on noticeboards etc. It may be necessary to have separate messages for different groups of people according to the type of ethical risk they may be exposed to.

Timing is also important, e.g. the team should be briefed in advance on any ethical matters arising for a specific scheme. Distributing the anti-bribery risk assessment to the team ensures they are aware of the risks and control measures.

Externally, the same principles should be considered when establishing communication channels to reach ‘interested parties’ such as clients and stakeholders. This enables the organisation to convey in its messaging what is important to itself, ethically.

[edit] Performance evaluation and reporting

Performance evaluation is, in itself, a chapter of ISO 9001 [3] and is associated with another of the ‘Leadership’ qualities sought in that standard: promoting improvement. To be successful, this must be done in a structured way and supported by leaders with a commitment to improve, using an evidence-based approach. This becomes manifest in the feedback loop, titled ‘Learn’, in the anti-bribery process above.

Performance evaluation can be against set objectives. It can also use results from regular sources such as procurement data (e.g. quantity of products and type of ethical sources used), nonconformity reports, internal audit reports and customer feedback including compliments and complaints.

Performance evaluation can be kept simple. It is recommended this is categorised by risk presented., e.g. for type of incident.

An ethical reporting format

| Type of incident | Occurr-ence(s) | Determination of significance | Actions (initial & full) |

| Fraud | 3 | People’s wages continued to be paid after leaving organisation. | Investigate payroll and finance functions. Financial audit. |

| Bribery | 1 | Subcontractor sought to unduly influence Procurement team decision | Investigate this occurrence and Subcontractor’s past performance on bids. Spot check records for other Subcontractors. |

| Modern Slavery | 1 | Subcontract labour appear to be accommodated in unhealthy conditions. Concern over gangmaster culture. | Assess evidence. Audit pay and conditions with Subcontractor, e.g. unannounced check of the accommodation with Subcontractor. Make other Subcontractors aware that an intervention has taken place. |

| Conflict of Interest | 2 | Bidding for work on a major infrastructure scheme where our people in another part of the organisation have project knowledge that could give an unfair advantage to our bid. | Identify extent of the potential Conflict, e.g. record in a plan. Put up professional ‘walls’ between those conflicted and the bid team. Brief all concerned. Withdraw if necessary. |

| Corruption | 1 | Contractor conspiring with a Subcontractor for them to receive payment for invoices for work that has not been carried out. | Investigate procurement function. Financial audit. |

| Anti-competition | 1 | Local concern that the scheme was not tendered, being pre-positioned between client, Contractor and its associates. | Conduct investigation to check that no advantage was gained through unfair access to information. |

| Confidentiality issue | 1 | Publication of confidential information about the scheme in the press appears to be traceable to a conversation with our site team. | Alert organisation’s press team to manage response to the issue. Carry out investigation to establish source. Brief the wider site team on the importance of confidentiality on this scheme. |

| Treatment of staff | 1 | Privacy: potential for some of an employee’s personal details to be released in a company communication. | Identify vulnerability. Audit compliance with Data Protection legislation. |

It is important that performance evaluation is both qualitative and quantitative. E.g. the number of occurrences and costs arising (quantitative) gives an idea of the scale of the problem whereas qualitative analysis helps get to the root cause and enables appropriate actions to be identified.

The interval of reporting can be determined by the number, frequency and/or severity of occurrences, for instance quarterly may be appropriate.

Learning from performance evaluation must be applied back in the business to promote a culture of improvement. After all, anti-bribery and ethical threats can change meaning that risk assessment would need to be reconsidered.

As with quality, evaluation of ethical performance can be assimilated through the Management Review process to provide a formal reporting chain.

With reporting, it is important to establish to whom you are reporting; again, this is about understanding who make up the audience you are communicating with, and their interest:

- External stakeholders, e.g. Client, Regulatory Body, Legal Authorities;

- Internal stakeholders, e.g. the organisation’s people for whom this may become a confidence issue in the perceived ethical credentials of their leadership.

An open and honest dialogue with all stakeholder groups is more likely to see a matter concluded and any damage to the organisation’s reputation restricted. It is not in the organisation’s interests for the matter to drag on, either in a legal process or in the media.

[edit] Whistleblowing & investigation

Transparency in communications is key to ensuring that your audience, internal and external, can have confidence that an ethical breach is being taken seriously, that improvements are being identified and that actions will be implemented. The significance of getting your message through to internal customers should not be under-estimated. Morale within the organisation could be damaged by ethical concerns and may result in good people leaving.

Reporting an actual or suspected ethical incident, also known as Whistleblowing, can be done via line management and / or by using a confidential telephone hotline; if the Employer provides one. Where recognised, Trades Unions can also support, and there are national telephone services such as ‘Crimestoppers’ in the UK.

Interestingly, in this case, transparency in the approach to ethical behavior can require confidentiality. For instance, the Whistleblower themselves must be entitled to it and, also, witnesses who provide evidence to the investigation, as they might feel that their work situation could be compromised with colleagues if their involvement was known.

It is important for an effective investigation to appoint, as members of the investigation team, people who are independent of the function in question. It can also be beneficial for that team to have legal advice available should the matter involve a potential breach of the law.

When presenting about an investigation to a legal authority, e.g. regulating body, having an auditable trail of records is key to show compliance with law and procedure. It can also protect against unfounded allegations of bribery. Foremost among the records required would be the organisation’s Legal Register and Anti-Bribery Risk Assessment.

Learning from an Investigation must be applied back in the business so that any weaknesses identified in operations can be addressed and improvements made. Again, the anti-bribery process above shows this as a feedback loop, titled ‘Learn’, to the beginning where anti-bribery risk assessment can be reconsidered.

[edit] Conclusion

Openness and honesty are increasingly sought-after attributes in the dealings of public and commercial organisations including those in the construction industry. Modern access to communication channels such as the Internet can make the outing of transgressions swift and widely known. In the UK, anti-bribery law has been strengthened to apply to all UK companies wherever they operate in the world.

An organisation needs to understand the ethical risks to which it is exposed which can include examples given here. Furthermore, it must be clear how it is assured that it behaves ethically in its relationships with all its stakeholders (internal and external, including supply chain) - and receives the same response in return.

This article shows that anti-bribery and ethical approaches can be considered as part of a quality management system. Consistent with ISO 9001 [3], a process approach is used to demonstrate how this can be done. Such a process is:

--ConSIG CWG 15:26, 16 Oct 2021 (BST)

[edit] Reference sources:

[1] Collins English Dictionary

[2] Bribery Act 2010 (UK)

[3] ISO 9001:2015 – Quality management systems – Requirements

[4] ISO 37001:2016 – Anti-bribery management systems – Requirements with guidance for use

[5] ISO 31000:2018 – Risk management - Guidelines

[6] Modern Slavery Act 2015 (UK)

[7] www.transparency.org - Corruption Perceptions Index

[8] ISO 9000:2015 – Quality management systems – Fundamentals and vocabulary

Rev 1.0: Original article written by Kevin Rogers & reviewed by Colin Harley on behalf of the Construction Special Interest Construction Working Group (ConSIG CWG). Article peer reviewed and accepted for publication by ConSIG 16/10/2021.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings for people to come home to... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.

Futurebuild and UK Construction Week London Unite

Creating the UK’s Built Environment Super Event and over 25 other key partnerships.

Welsh and Scottish 2026 elections

Manifestos for the built environment for upcoming same May day elections.

Advancing BIM education with a competency framework

“We don’t need people who can just draw in 3D. We need people who can think in data.”