Edwin Rickards

|

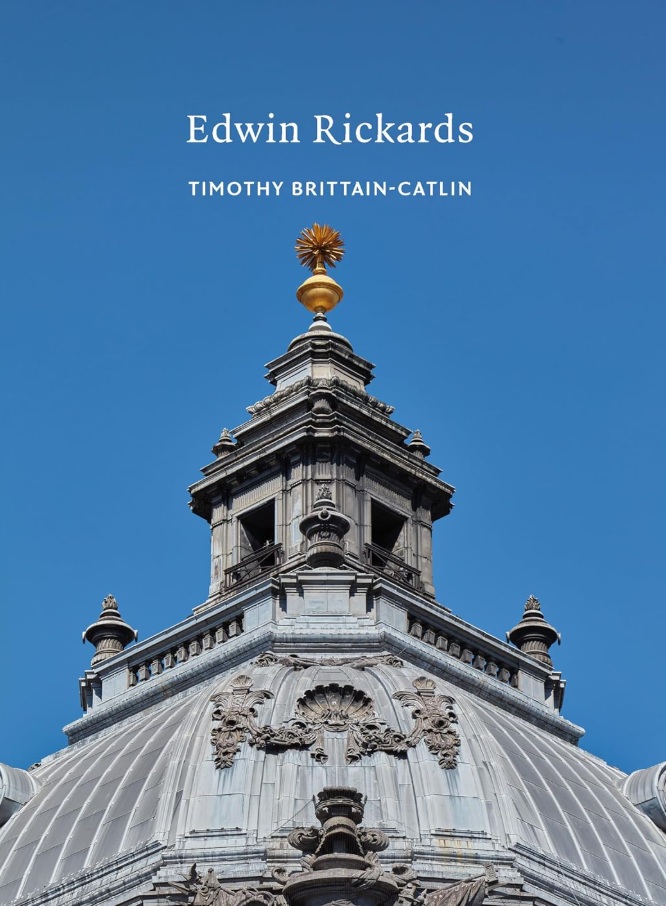

| Edwin Rickards, Timothy Brittain-Catlin, Liverpool University Press on behalf of Historic England, 2023, 156 pages, 81 colour and black-and-white illustrations, paperback. |

In this well-illustrated book (the latest in the Victorian Society’s invaluable series on Victorian and Edwardian architects), which includes many high-quality contemporary photographs of Rickards’ buildings, and reproductions of his architectural drawings, caricatures and accomplished watercolours, the author presents an engaging and lively review of Rickards’ professional life; and the book is enhanced by numerous references to his personal interests and friendships, notably his long and enduring one with the novelist, Arnold Bennett. This is made critical by the curious current absence of Rickards from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Born in London in 1872 to a lower-middle class background (his father ran a draper’s shop), Rickards showed from an early age remarkable skill in imaginative drawing. He harnessed this in his development as an architectural assistant, working for several practices while being admitted to the Architectural Association in 1890, where he later acted as a tutor and lecturer.

Brittain-Catlin suggests that ‘Rickards could have taken on any one of many different careers – including as a caricaturist or theatre designer – but he chose to be an architect above all else… transform(ing) himself… into a dandily dressed, charismatic figure who scarcely paused for breath (his passion for talking is said to have been inexhaustible and exhausting both for friends and others who met him) and who straddled both the demi-monde and the social and professional circles of leading Edwardian architects.’

Chapter 1 (‘Little Rickards’, an epithet given him by Charles Reilly who, despite a snobbish attitude to Rickards’ accent, was to become a life-long friend) provides the background to the formation of the partnership he was to enter in 1893 with James Stewart and HV Lanchester, primarily with the aim of entering architectural competitions. Lanchester was the senior of the three men (some nine years older than Rickards) and from a far wealthier background.

He was also more practical; the quotation Brittain-Catlin gives from J Warren’s contribution to Alastair Service’s pioneering 1975 study Edwardian Architecture and its Origins nicely illustrating the differences between him and Rickards. ‘In his enterprise and thorough understanding of structure and planning,’ Warren wrote, ‘Lanchester was fully a match for the indefatigable Rickards, whose Piranesian conceptions he had to tame, rationalise and build.’ This important contrast is nicely brought out by the author in his comparison of Lanchester and Rickards with other successful practices in the USA during this period. Certainly, it left Rickards free to express his more esoteric ideas and principles, influenced by what he had seen as a young man in Paris and Vienna, in his many superb drawings.

Chapter 2 (‘City of Palaces’) focuses on the partnership’s first major competition winner, Cardiff City Hall and Law Courts in Cathays Park (1897-1906). The author makes clear his regret that they did not win later competitions there, including that for the National Gallery and Museum of Wales. But he also includes a perceptive description and analysis of Deptford Town Hall (1902-5), ‘which although different in scale from the city hall at Cardiff, and on a tight site in a poor district of London, was again a kind of palace, which this time included a staircase that is one of the most powerful small spaces in English architecture.’

Hull School of Art, another jewel of a building, is an exact contemporary of Deptford Town Hall. It is described in both Chapter 3 (‘You never know your luck’), which provides a useful account of the vagaries and frustrations of Edwardian architectural competitions, and Chapter 4 (‘Material to the core’), which also includes an analysis of Lanchester and Rickards’ most colossal achievement, also won in competition, Methodist Central Hall, Westminster, built in 1905-12, and Rickards’ various designs for monuments, both executed and unexecuted.

The concluding chapter of the book (‘Big Rickards’) records Rickards’ volunteering (in his mid-40s) for military service in France and how this hastened his early death from illness, and it gives an account of his commission in 1918 for the unimplemented Canadian Imperial (War) Memorial in Ottawa.

This is a splendid book, with a comprehensive bibliography and a list of all Rickards’ executed works. The only minor quibble is the lack of plans of his larger buildings, which might have made the otherwise excellent descriptions of Cardiff City Hall and Law Courts and Methodist Central Hall, Westminster, slightly easier to follow.

This article originally appeared as ‘Piranesian conceptions’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 181, published in September 2024. It was written by Nicholas Doggett, managing director of Asset Heritage Consulting, a heritage consultancy based in Oxford.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

- Conservation.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- How architecture can suppress cultural identity.

- IHBC articles.

- IHBC launches climate change hub.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Architect.

- Architectural styles.

- Unlocking the Church: the lost secrets of Victorian sacred space.

- The Victorian Society's Top 10 Endangered buildings 2019.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.