Terraced houses and the public realm

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Terraced houses are defined as ‘‘a row of adjoining buildings where each building has a wall built at the line of juncture between itself and the adjoining property which provides structural support to itself and a building on the adjoining property." (1)

The ‘public realm ‘‘… relates to all parts of the built environment where the public has free access. It encompasses: all streets, squares, and other rights of way, whether predominantly in residential, commercial or civic uses...’’ (2)

The terrace is a key feature of the built environment in many UK cities and it is of great importance that its role in supporting not only indoor activity but outdoor activity is fully understood.

Is there a discernible difference between the public realm of a suburban street with detached housing and a street of terraced housing? The condition set up by suburban housing lends itself to large gardens, promotion of the motor vehicle, lack of street scale, limited community interaction and little passive security. The suburban condition gives neighbours and locals less chance to meet and socialise, i.e. create a thriving public realm. With neighbours ‘detached’ from each other there is less opportunity for community activity and relationships to form (3).

The terraced street creates a condition in which neighbours are more likely to meet, creates the opportunity for community spirit to develop, and provides passive security. ‘‘If there are many people on a street there is considerable mutual protection, and if it is lively, many people survey the street from their windows because it is meaningful and entertaining to keep up with events.’’ (4)

Jane Jacobs in response to prevalent urban planning policies of the 1960s suggested the idea of 'eyes on the street'5 where neighbours in low-rise high-density streets provide passive surveillance as people 'survey' the street. In 'The Death and Life of Great American Cities' she argued that urban planning was creating unsafe neighbourhoods and streets. There are parallels with current planning in the UK, where planning policies such as the Belfast Regeneration Plans and Pathfinder Schemes having been highly criticized for the demolition of sound terrace houses, the removal of historic terraced streets and the depletion of living public realm.(6)(7)

[edit] The relationship between housing and the public realm

‘‘Public space is all around us, a vital part of everyday urban life: the streets we pass through on the way to school or work, the places where children play, or where we encounter nature and wildlife; the local parks in which we enjoy sports, walk the dog and sit at lunchtime; or simply somewhere quiet to get away for a moment from the bustle of a busy daily life...”(8)

The public realm is the physical manifestation of community, it is the space that people inhabit outside of their homes, the space people use to socialise and where children play. The qualities of the public realm are integral to its use, whether it be a road between rows of terraces or a large landscaped park.

The conditions set up by a terraced street lend themselves to the build up of a successful public realm;

‘‘The layouts of terraced properties present many positive qualities, including definition of public and private realm, densities that support the provision of services within walking distance, connected street layouts and strong urban form and character.’’(11)

A terraced street is more than just the sum of its parts, it forms the edge to the public realm and allows social interaction to occur. The linear nature of terraced streets provides locals and passers-by with direct walking routes and a clear definition of public and private. The close proximity of property entrances increases the likelihood of neighbours meeting regularly, forging relationships and creating a local ‘spirit’. Thresholds act as a filter between public and private.

In many terraces in Amsterdam, locals see the street as an extension of the living room. In central Amsterdam you will notice terraces with large windows facing onto main streets, often without curtains with passers-by given a glimpse into the resident's 'private realm'. This is partly why Dutch architects have been able to push the boundaries of housing design, as their culture is more relaxed about personal space and privacy in the home. In the UK in contrast, houses tend to be more ‘gated’, with small gardens, bin stores, and an array of other devices employed in an attempt by the inhabitants to create privacy, whether physical or psychological.

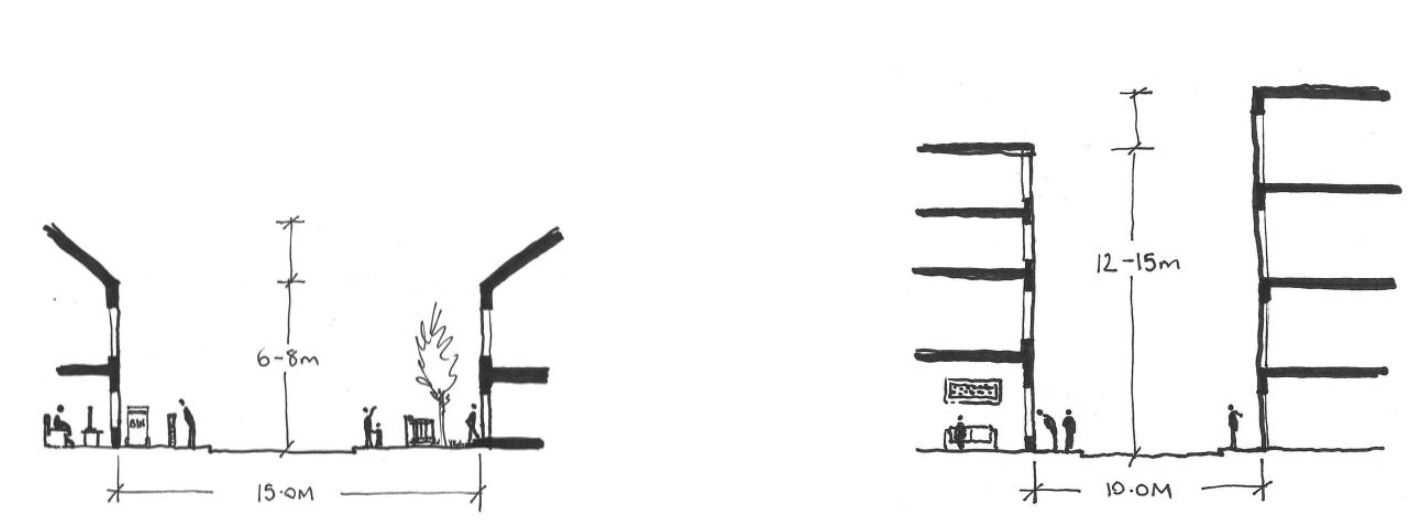

Indicative terraced street sketches. Left: Typical Belfast street section. Right: Typical Amsterdam street section.

The quality of public realm has a direct correlation with the activity and movement within an area, ‘‘In streets and city spaces of poor quality, only the bare minimum of activity takes place… People hurry home.’’(14) As Jan Gehl explains, whereas in pleasant streets people are more likely to enjoy a walk, meet friends, socialise and create ‘activity’.

‘‘Living cities, (are) therefore ones in which people can interact with one another, are always stimulating because they are rich in experiences, in contrast to lifeless Cities, which can scarcely avoid being poor in experiences and thus dull, no matter how many colours and variations of shape in building are introduced.’’(15)

Without a regular footfall, wide, empty streets and large spaces can feel vast and unwelcoming. Busy living streets typified by city centre terraces have a human scale, defined form and visual.

[edit] Scale

Scale is a key element of design when thinking about the relationship between the terrace and the public realm.

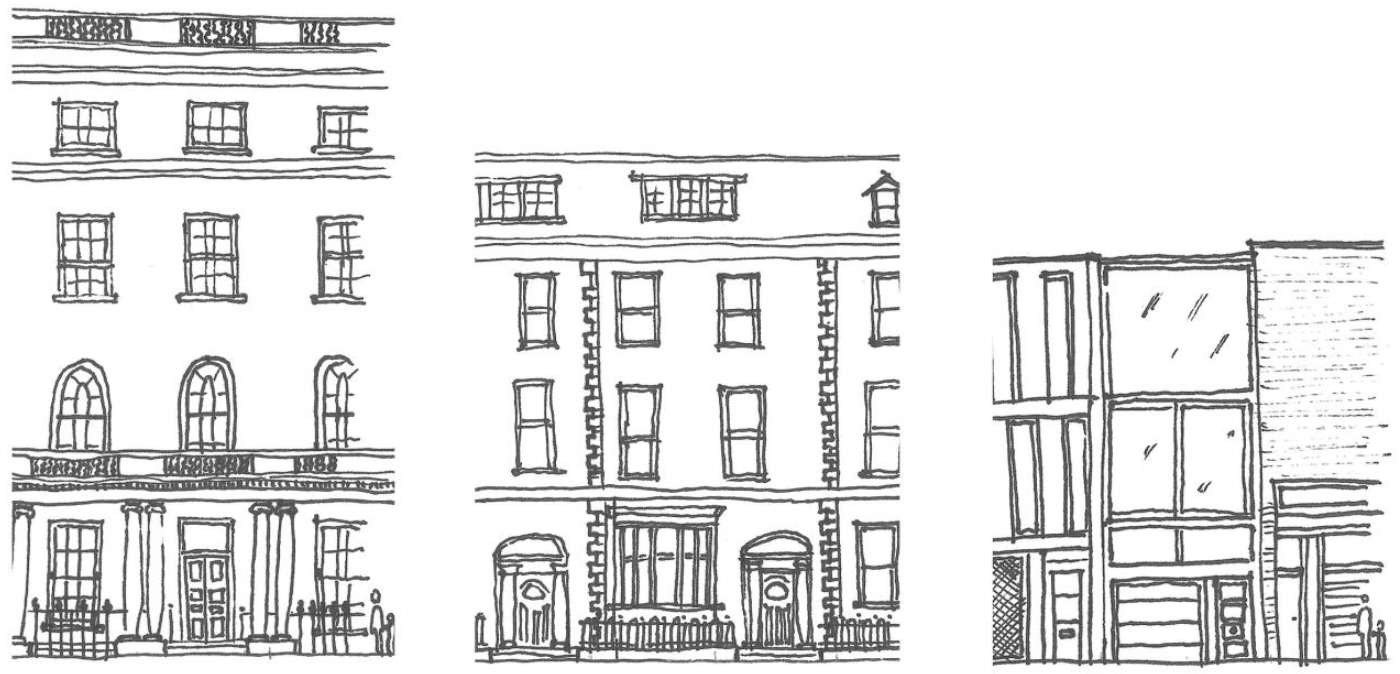

Sketch terrace frontages. Left to right: Park Crescent, University Square, Borneo (Plot 18).

If a frontage is thoughtfully scaled and detailed the terrace can engage with the passing public, provide shade and offer visual stimulus. John Nash's design for the terraces at Park Crescent was part of a grand scheme and accordingly the scale and proportions of the terrace are of a grand nature. In an attempt to communicate with the passing public, Nash designed the detailing of the ground floor (public eye-level) with carefully scaled architectural ornamentation. Features such as the human scale columns with Ionic capitals and the cast iron spear-headed railings give the terrace a grand but civic feel.

Case study frontages. Left to right: Park Crescent, University Square, Borneo.

The Victorian terrace at University Square is a much less grand, however it still exerts a presence on the street. The architect Thomas Jackson, much like Nash at Park Crescent, utilised human-scale columns in his terrace design framing each doorway and giving each terrace its own entrance. Architectural features such as quoins and shifting bay windows are also used across the breaking the repetition of a street long terrace.

At Borneo-Sporenburg one of the most successful aspects of the scheme is the varying of the frontage in terms of composition, materiality and colour. The height of the terraces stays relatively constant throughout and the differing facade treatments allow each terrace unit to have its own personality. The effect of scale at Borneo narrows the 'vehicular realm' giving locals a much greater feeling of ownership of the street and making it feel like a safe place to be.

[edit] Threshold

If a buildings door handle is known as its handshake, then a buildings threshold is the build up to that handshake. A terrace's threshold is an important part of its design and each of the three case studies has a distinctly different threshold.

The threshold condition at Park Crescent creates a successful transition between private and public realm. The colonnaded porch acts as a semi-public zone, providing both inhabitants and passers-by with an area of shelter. With two steps up to the porch and a further step to the doorway, the internal floor level is set around 200-500mm above external ground level (this varies across the terrace). This subtle stepping up gives an added sense of privacy internally. The wide footpath reduces the negative impact of the busy road and the colonnaded porch provides cover from bad weather.

University Square terrace has a generous garden which acts in a similar fashion to the porch and colonnade as a transition between public and private. University terrace is also situated on a busy road, where car parking is located either side of a single lane of traffic. The garden area is divided from the pedestrian footpath with a short wall and decorative iron railings, which give an impression of division but are not ‘unfriendly’ to passers-by. The terrace entrances are raised above the garden level by a single step, with the garden in turn raised above street level by one to ten steps across the terrace from East to West. This step up from the public street, similar to Park Crescent, raises the terrace above the road level giving inhabitants privacy and helps to define the public, semi-public and private realms.

Perhaps the most straight-forward threshold of the three case studies is at Borneo-Sporenburg, although as the development is varied, there are several different threshold conditions. Generally the terrace entrances open up directly onto the street. This is the minimum possible division between public and private, indeed the internal entrance hall acts as the semi-private zone. At Plot 18 and the neighbouring terraces the passing public are given a glimpse into the lives of inhabitants as eye level windows line the street. Effectively, the visible hallway and front room become the threshold. This type of threshold condition is utilised due to tight land restrictions but it also reflects traditional Dutch row housing design. The threshold condition does not allow for much external space, although many locals have taken to adding planting and outdoor furniture.

[edit] Services

When originally installed many of the services located at Park Crescent were external; above the ground and part of the public realm. Indeed as the terrace was built in the early 19th century even the sewers would probably have been located on the street(20).

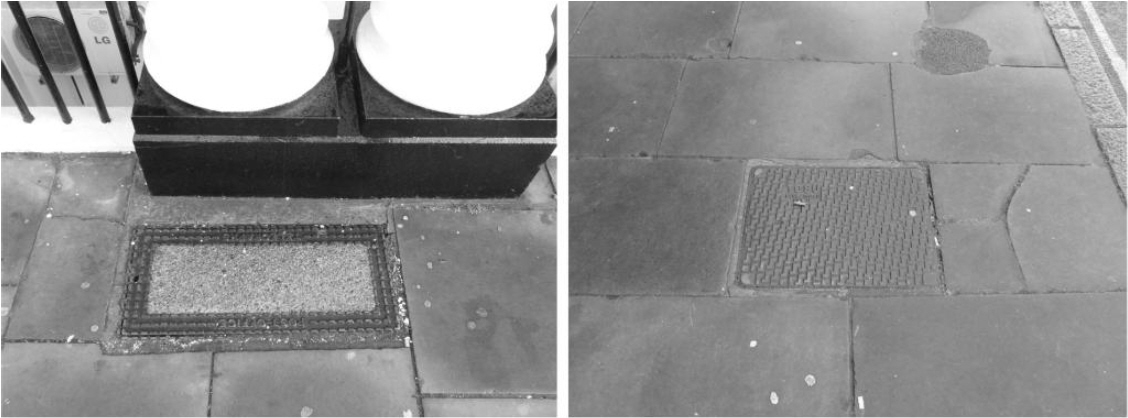

Today, services are located beneath the ground to minimise the impact on the public realm; including sewerage, power and telephone lines. The major impact of services on terraces is the location of man-holes and other services ground covers.

Services man-hole covers embedded in pedestrian pavement at Park Crescent.

Services man-hole cover embedded in road at Borneo-Sporenburg.

At Park Crescent and University Square there are numerous service panels which break up the public footpaths, with telephone, television and other services breaking up paving patterns. This contrasts with the modern terraced streets at Borneo-Sporenburg, where all service panels and covers are located in the road.

[edit] Public interaction and sense of community

At Park Crescent there is little apparent interaction or sense of community, with buildings now predominantly used as offices and access to any living accommodation being located to the rear of the terrace. The terraces location in the city centre provides high levels of public usage and footfall, however, even though it is popular walking route, there is no perceptible community spirit due the displacement of living accommodation to the upper floors and the lack of street front entrances. These conditions reflect the changes made to the terrace after damage suffered in World War II, when the terrace was rebuilt to suit modern office requirements.

At Borneo-Sporenburg there is much communal activity all year round, due to its principal usage as housing and its high population density. The high density and street front entrances allow neighbours to meet regularly and help to build community spirit.

Street activity. Left to right: Park Crescent, University Square, Borneo-Sporenburg.

As part of Queens University's Law faculty, the terrace at University Square sees much student interaction and consequently the build up of a student community spirit. The terrace is in constant use during day and night throughout the week thanks to its functions as lecture rooms, offices and a cinema. This ensures regular footfall, plentiful interaction and also gives the terrace a unique community spirit. It only functions during the term-time, but despite this, it plays an important role in creating a vibrant local public realm.

[edit] Conclusion

‘‘Like some vast umbilical cord of unbroken brick, terraced houses extend from north to south, east to west, connecting rich and poor, past and present’’(24)

This quote from an article on the rise and fall of the popularity of terraced housing summarises the significance of terraces and their importance in supporting the public realm. Terraces are universal, they offer a longitudinal connection between places and allow a unique form of public realm to be established. At Borneo the equality in the size of the terraces brings a relaxed attitude and goes some way to equalising the perceived gap in housing conditions between the rich and poor. At Borneo around 30% of the terraces are social housing. This mix is important in creating a respectful and inclusive community and in turn, creating positive public realm.

The master plan strived to create a 'wide ranging social arena' and this has given rise to the successful support of a dynamic public realm. Bold moves such as locating 2500 dwellings in such a high density, with narrow frontage terracing, each with their own front door, limiting green space and putting people before vehicles. It is these decisions that have lead to the successful creation of a modern high density community, with less importance placed on the number and area of green spaces but rather on quality and excellence in the streetscape

At Park Crescent, John Nash not only brought the grand terrace to the masses but provided a grand social landscape incorporating Regent's Park into the terrace realm.

‘‘The public realm... is derived as much from the spaces between the buildings as from the architectural quality of the buildings themselves. There is often a carefully composed relationship between the private and public realms, forming an essential part of local distinctiveness and placemaking.’’'26

The ability to support public realm is wholly dependent upon the spaces between the buildings and the threshold between public and private realms.

At University Square, the terrace was placed into an existing cityscape. This is in direct contrast to Park Crescent and Borneo which were both new additions to their respective cityscapes, allowing them full reign to fuse public and private, internal and external spaces, into a cohesive whole. The result in both cases is a highly successful terrace scheme.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Architectural styles.

- Back-to-back housing.

- Ballymun mass housing and regeneration.

- Bin Blight.

- British post-war mass housing.

- Changing lifestyles.

- Housing contribution to regeneration.

- Masterplanning.

- Picturesque movement.

- Public realm.

- Public space.

- Smart cities.

[edit] External references

- (1) The Planning (Subterranean Development) Bill [HL] 2015-16.

- (2) ENGLISH HERITAGE (2007) Suburbs and the Historic Environment. English Heritage Publication. Pg 6.

- (3) GEHL, J., (2003). Life Between Buildings - Using Public Space. 5th edn. Skive, Denmark: The Danish Architectural Press. Page 170.

- (4) Ibid.

- (5) JACOBS, J., (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. 1st edn. New York: Random House Inc.

- (6) MOYE, C., (2007) The rise and fall of a British favourite, The Telegraph,12 Apr 2007.

- (7) MINTON, A., (2009) Razing the Roots, The Guardian, Wednesday 17 June 2009.

- (8) Lipton, S., (2004) The Value of Public Space, CABE Publication. Accessed at: http://www.cabe.org.uk/files/the-value-of-public-space.pdf. Accessed on: 18th Jan 2012.

- (11) CABE, (2005) Creating Successful Neighbourhoods, CABE Publication. Page 15. Accessed at: http://www.cabe.org.uk/files/creating-successful-neighbourhoods.pdf Accessed on: 18th Jan 2012.

- (14) GEHL, J., (2003) Life Between Buildings - Using Public Space. 5th edn. Skive, Denmark: The Danish Architectural Press. Page 13.

- (15) Ibid. Page 23.

- (20) LEMANN, M., (2010) Waste Management. 1st edn. Bern: Peter Lang AG Publishers.

- (24) MOYE, C., (2007) The rise and fall of a British favourite, The Telegraph,12 Apr 2007.

- (25) Insertion of six lane artery road to centre of London - Marylebone Road.

- (26) ENGLISH HERITAGE, (2007) Suburbs and the Historic Environment. English Heritage Publication. Pg 6. Accessed at: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/content/publications/docs/suburbshe20070802122533.pdf.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?