Construction disputes

|

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Stella Rimmington, former Director General of MI5, made this comparison in her autobiography Open Secret (2002):

'...the Thames House Refurbishment was fraught with difficulties. It was clear that dealing with the building industry was just as tricky as dealing with the KGB.'

In 2013, an NBS survey, the National Construction Contracts and Law Survey, found that 30% of firms had been involved in at least one dispute in the previous 12 months. As a consequence, there is enormous interest in construction disputes but it tends to focus on dispute resolution techniques rather than how to avoid them.

NB Research published by Arcadis in 2020 found that disputes are resolved in the UK faster than anywhere else in the world, at an average of 9.8 months. Ref https://www.arcadis.com/en/united-kingdom/our-perspectives/2020/june/global-construction-disputes-2020/

[edit] Why do construction disputes occur?

A combination of environmental and behavioural factors can lead to construction disputes. Projects are usually long-term transactions with high uncertainty and complexity, and it is impossible to resolve every detail and foresee every contingency at the outset. As a result, situations often arise that are not clearly addressed by the contract. The basic factors that drive the development of construction disputes are uncertainty, contractual problems, and behaviour.

[edit] Uncertainty

Uncertainty is the difference between the amount of information required to do the task and the amount of information available (Galbraith, 1973). The amount of information required depends on the task complexity and the performance requirements, usually measured in time or to a budget. The amount of information available depends on the effectiveness of planning and requires the collection and interpretation of that information for the task.

Uncertainty means that not every detail of a project can be planned before work begins (Laufer, 1991). When uncertainty is high, initial drawings and specification will almost certainly change and the project members will have to work hard to solve problems as work proceeds if disputes are to be avoided.

[edit] Contractual problems

Standard forms of contract clearly prescribe the risks and obligations each party has agreed to take. Such rigid agreements may not be appropriate for long-term transactions carried out under conditions of uncertainty.

It is not uncommon to find amended terms or bespoke contracts that shift the risk and obligations of the parties, often to the party least capable of carrying that risk. Where amended terms or bespoke contracts are used, they may be unclear and ambiguous. As a consequence, differences may arise in the parties' perception of the risk allocation under the contract. Where the parties have agreed to amended or bespoke terms, those conditions take effect in addition to the applicable law of the contract, which is continually evolving and being refined to address new issues.

NB: The annual ARCADIS Global Construction Disputes Survey found that contract administration was the main cause of disputes on construction projects for four years running.

[edit] Behaviour

Since contracts cannot cater for every eventuality, wherever problems arise either party may have an interest in gaining as much as they can from the other. Equally, the parties may have a different perception of the facts. At least one of the parties may have unrealistic expectations, affecting their ability to reach agreement. Alternatively, one party may simply deny responsibility in an attempt to avoid liability.

[edit] Common causes of construction disputes

Construction is a unique process which can give rise to some unusual and unique disputes. However, research in Australia, Canada, Kuwait, the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that a number of common themes occur quite frequently:

[edit] Acceleration

It is not uncommon for commercial property owners to insist upon acceleration of a construction project. Such examples might include the completion of a major retail scheme, and the need to meet key opening dates or tenant occupation in an office development. The construction costs associated with acceleration are likely to be less than the commercial risk the developer may face if key dates are missed.

The circumstances surrounding acceleration are often not properly analysed at the time the decision is made, and that inevitably leads to disputes once the contractor has carried out accelerative measures and incurred additional costs only to find that the developer refuses to pay.

The construction of facilities in Athens for the Olympic Games 2004 were subject to acceleration, and a wealth of disputes were expected once the facilities were completed and the euphoria of the games had subsided.

[edit] Co-ordination

In complex projects involving many specialist trades, particularly mechanical and electrical installations, co-ordination is key, yet conflict often arises because work is not properly co-ordinated. This inevitably leads to conflict during installation which is often costly and time-consuming to resolve, with each party blaming the other for the problems that have arisen.

Ineffective management control may result in a reactive defence to problems that arise, rather than a proactive approach to resolve the problems once they become apparent.

[edit] Culture

The personnel required to visualise, initiate, plan, design, supply materials and plant, construct, administer, manage, supervise, commission and correct defects throughout the span of a large construction contract is substantial. Such personnel may come from different social classes or ethnic backgrounds.

In the UK, skill shortages have led to an influx of personnel from central and eastern Europe, a trend likely to continue with the growth of pre-accession states seeking access to the labour market in the European Union.

Major international construction projects may employ or engage people from different nationalities and cultures. For example, on a major pipeline contract in Kazakhstan the owner was a joint venture comprising Kazakh, Canadian and British companies, and the owner's representatives on the project for day-to-day matters were of Canadian, French, Russian and British nationalities.

The contractor was a Greek–Italian joint venture that employed labour from no fewer than 24 different countries throughout central and eastern Europe, the Middle East and the Indian sub continent. Forming a teamwork approach across cultures can be very difficult where each culture has its own values.

[edit] Differing goals

Personnel engaged on a large construction contract are likely to be employed by one of many subcontracted firms, including those engaged as suppliers and manufacturers. Each of these firms may have its own commitments and goals, which may not be compatible with the others and could result in disputes.

[edit] Delays

Disputes frequently arise in respect of delays and who should bear the responsibility for them. Most construction contracts make provision for extending the time for completion. The sole reason for this is that the owner can keep alive any rights to delay damages recoverable from the contractor.

On international construction projects, the question of any rights the contractor might have to extend the time for completion was a matter often addressed towards the end of the contract, when an overrun looked likely. From the owner's point of view, this made the examination of the true causes of delay problematical and inevitably led to disputes between the contractor and the owner as to the contractor's proper entitlement.

Under FIDIC (International Federation of Consulting Engineers) contracts, the contractor is now required to give prompt notice of any circumstances that may cause a delay. If the contractor fails to do so, then any rights to extend the time for completion will be lost, both under the contract and at law.

This may seem a harsh measure, but a better view is that this approach brings claims to the surface at a very early stage and gives the recipient an opportunity to examine the cause and effect of any delay properly as and when it arises, so that the owner has some say in what can be done to overcome the delay.

[edit] Design

Errors in design can lead to delays and additional costs that become the subject of disputes. Often no planning or sequencing is given to the release of design information, which then impacts on construction. Equally, the design team sometimes abrogates its responsibilities for the design, leaving the contractor to be drawn into solving any design deficiencies by carrying out that part of the work itself to try to avoid delays, and, in doing so, innocently assuming the risk for any subsequent design failures.

[edit] Engineer and employer's representative

The personality of the engineer or the employer's representative and their approach to the proper and fair administration of the contract on behalf of the employer is crucial to avoiding disputes, yet a substantial proportion of disputes have been driven by the engineer or the employer's representative exercising an uneven hand in deciding differences in favour of the employer.

In domestic and international contracts, the engineer traditionally had an independent and impartial role. This independence or impartiality was often not properly exercised, and in some cases there was clear evidence of bias by the engineer towards the employer. This practice was not limited to third world countries but also existed in developed countries.

It is a complete fiction to say that the engineer under government contracts in the UK could possibly act independently of the employer on every issue.

Some contracts are open regarding constraints imposed on the engineer: in Hong Kong engineers are subject to financial constraints in respect of variations and in the extensions of time that can be given. While this may be understandable from a public policy point of view, it is unacceptable for it to be undertaken behind a veil so that the fiction of independence is preserved.

Under FIDIC contracts, the engineer no longer has an impartial role but expressly acts for the employer. This does not prevent the engineer from taking a professional view on the merits of any difference that may be at issue, but in the event of a dispute the mechanism to resolve such matters quickly by independent means has been achieved by the introduction of a dispute adjudication board.

[edit] Project complexity

In complex construction projects the need to carry out a proper risk assessment before a contract is entered into is paramount: yet this is often not done.

There are numerous examples of projects taking much longer than planned and contracted for because there was insufficient appreciation of the risks associated with the project's complexity. Inevitably, the delay and additional costs the contractor incurs, and the owner's right to claim damages for delay, often develop into bitter disputes.

[edit] Quality and workmanship

In traditional construction contracts, disputes often arise as to whether or not the completed work is in accordance with the specifications. The specification may be vague on the subject of the dispute in question, and each party to the contract may have a different view on whether the quality and workmanship is acceptable.

This is even more so in international contracts. Although great care may have been taken to prescribe the quality of the materials and their compliance with European standards, these standards may contradict the local laws and regulations in the country where the project is being constructed, and any dispute will be governed by the law of that country.

In design and build contracts, perhaps the greatest deficiency is in the contract documentation, particularly the employer's requirements. This inadequacy inevitably leads to claims by the contractor for additional costs, which, if not resolved, can lead in turn to costly disputes.

[edit] Site conditions

If the contract inadequately describes which party is to take the risk for the site conditions, disputes are inevitable when adverse site or ground conditions impede the progress of work or require more expensive engineering solutions.

Even if the employer, in good faith, provides detailed information on the site conditions to the contractor, if that information is discovered to be incorrect and the contractor has relied on it and acted upon it to their detriment, the employer may be liable to the contractor for the consequences.

[edit] Tender

The time allowed to scrutinise the tender documents, prepare an outline programme and methodology, carry out a risk assessment, calculate the price, and conclude the whole process with a commercial review is often impossibly short. Mistakes in this process may have an adverse effect on the successful commercial outcome of the project.

A culture may be engendered in the contractor of pursuing every claim that has a prospect of redressing any ultimate financial shortfall. This approach does nothing to foster close and co-operative working relationships between the owner and the contractor during the progress of the work, and inevitably leads to disputes.

[edit] Variations

Variations are a prime cause of construction disputes, particularly where there are a substantial number, or the variations impact on partially completed work or are issued as work is nearing completion. The nature and number of variations can transform a relatively straightforward project into one of unmanageable complexity. The new Parliament building in Edinburgh is such an example.

The building was planned to house 329 people, but through variations, the building increased in size and complexity to house 1,200 people. It was perhaps not surprising that the total cost of construction exceeded £500m, almost ten times more than the original budget.

[edit] Value engineering

This term often lacks definition in construction contracts and can lead to disputes, particularly where the saving is to be shared between the contractor and the owner. Savings in respect of the supply and installation of the material or product in question might be relatively easy to determine and agree, but these are not the only benchmarks, and a proper value engineering approach needs to take full account of the lifecycle costs of any proposed change.

[edit] Research

The Global Construction Disputes Report published by Arcadis in 2019 found that the UK remains the jurisdiction with the shortest average length of time to solve a dispute at 12.8 months, and that the average value of disputes in the UK has fallen 47% to US$ 17.9 million. Negotiation remains the preferred method of resolution.

[edit] Dispute resolution

For further guidance on methods of dispute resolution see:

This article was written by the University College of estate management, Reading 13:00, 11 December 2012 (UTC)

--University College of Estate Management (UCEM)

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Addendum.

- Adjudication.

- Adversarial behaviour in the UK construction industry.

- Alternative dispute resolution.

- Arbitration.

- Bespoke construction contract.

- Civil procedure rules.

- CLC document on claims and disputes in construction.

- Clear contracts during uncertain times.

- Compensation event.

- Compulsory Alternative Dispute Resolution.

- Conflict avoidance.

- Conflict of interest.

- Construction operations.

- Contract claims.

- Contractual right.

- Cost overruns.

- Defects.

- Delay analysis.

- Delays on construction projects.

- Dispute avoidance.

- Dispute resolution.

- Dispute resolution board.

- Dispute resolution procedure.

- Disruption claims in construction.

- Expert evaluation.

- Expert witness.

- Extension of time.

- How does arbitration work?

- How to give professional advice to friends.

- International research into the causes of delays on construction projects.

- Liquidated damages.

- Loss and expense.

- Mediation.

- Modifying clauses in standard forms of contract.

- Negotiation techniques.

- Pressing pause to avoid errors.

- Relevant event.

- Risk assessment.

- The causes of late payment in construction.

- Value management.

- Variations.

- What is a default?

[edit] External references

- nbs: National Construction Contracts and Law Survey 2013.

- Fenn P (2002) 'Why Construction Contracts Go Wrong (an Aetiological Approach to Construction Disputes)', Society of Construction Law, London.

- Fenn P, Lowe D and Speck C (1997) 'Conflict and Disputes in Construction', Construction Management and Economics, Volume 15, page 513.

- Al-Sabah SJ, Fereig SM and Hoare DJ (2002) 'Construction Claims – The Results of Major Tribunal Findings in Kuwait', Arbitration, Volume 68, Number 1, page 11.

- Arcadis, Global construction disputes report 2018.

Featured articles and news

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

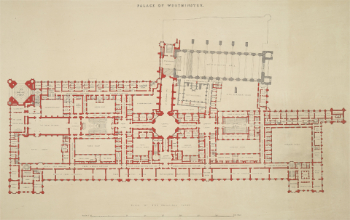

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

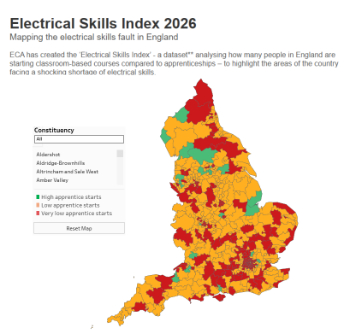

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.