Landscapes of human exploitation

This article originally appeared in Context 108, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in March 2009. It was written by Fiona Newton.

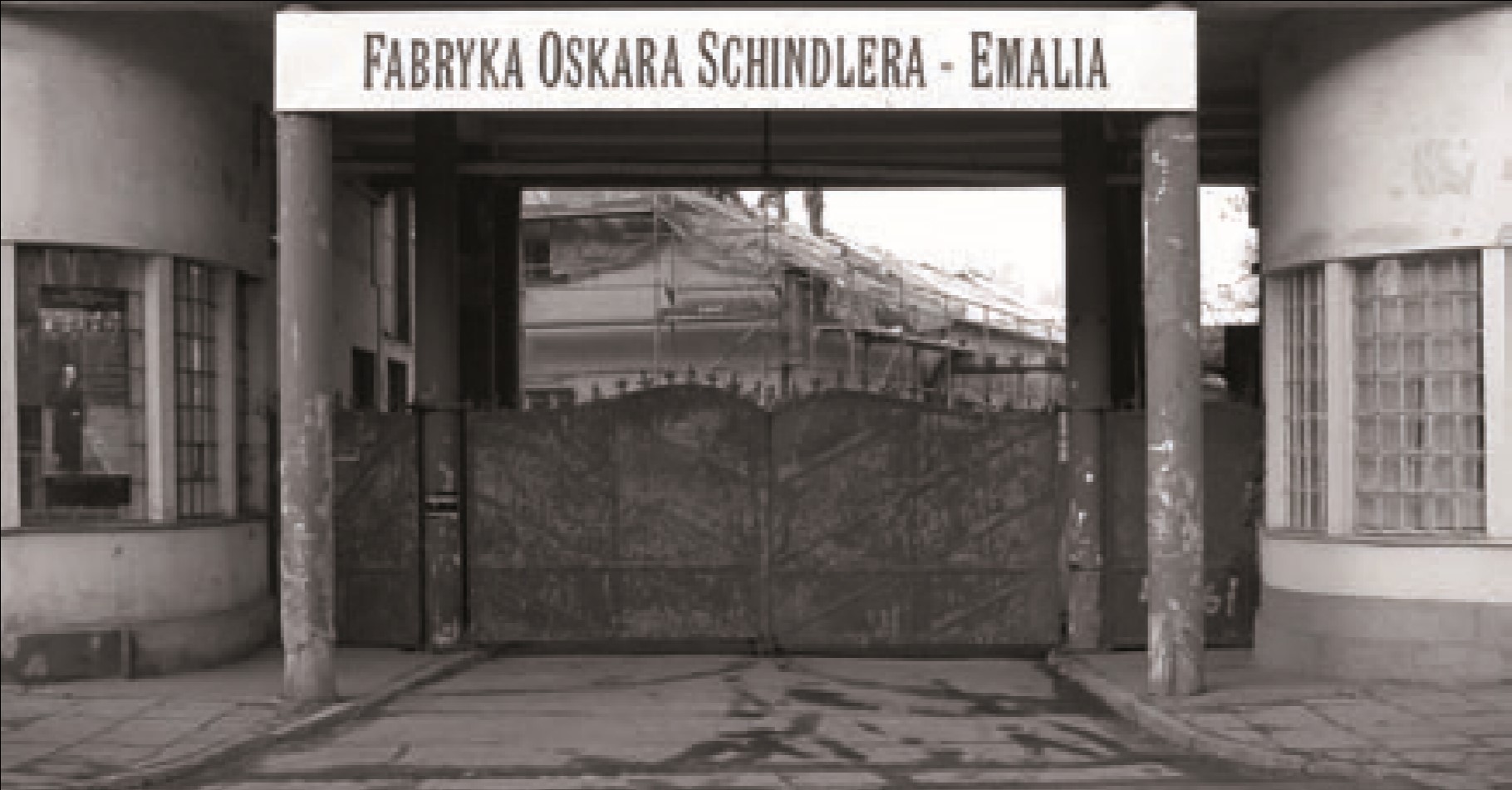

[Image: The 1937 metalwork factory on Lipowa Street in the Podgórze district of Krakow became Deutsche.]

Sixty per cent of people in the UK under the age of 35 have never heard of Auschwitz. How do we conserve the 20th century’s most dreadful heritage?

Contents |

Introduction

Are we consistent in our celebration, commemoration or protection of uncomfortable aspects of history? How have sites which relate to a single snapshot of history been treated, valued in different ways, or perhaps not valued at all?

Perhaps by examining sites in a single area, held together by their involvement in one ‘story’, we can see varied levels of conservation and commemoration which typify a disparate reaction to the uncomfortable history of Nazi genocide across Eastern Europe. The state of preservation and the level of remembrance of the ghetto area and forced labour camps around the Polish city of Krakow are perhaps typical of many towns and cities in that area. Looking at sites around this city and one small story in its wartime history we can examine how successive generations are treating a harrowing history.

Deutsche Emalwarenfabrik Oscar Schindler

Steven Spielberg’s ‘Schindler’s List’ is a film based on a novel, Schindler’s Ark by Thomas Keneally, but that in turn is a fictional interpretation of historical fact. It is an example greater than most of the blurring of boundaries between fact and fiction, between myth and reality. The locations that shaped the story, in truth and in Hollywood, also draw us to examine the presentation of commemoration and the preservation of this uncomfortable history.

Oskar Schindler, a Sudetan German, arrived in Krakow in 1939 to make money. He was a profiteering opportunist and a member of the Nazi party with a playboy lifestyle, a flawed character who, in turn, surrendered his fortune and risked his life to save over a thousand people from certain death.

Initially Schindler used his influence and panache to seek out confiscated Polish property. He established his factory Deutsche Emalwarenfabrik Oscar Schindler (Emalia) in a 1937 metalwork factory on Lipowa Street, Podgórze, and began producing enamel kitchenware for the German army. Podgórze was, and is still, an industrial area close to that which became the Jewish ghetto.

Other factory owners were encouraged to move their production into the nearby Plaszów camp. Schindler was allowed, at a cost, to accommodate his workforce and production outside the camp. He bought a plot of land adjacent to the factory and obtained permission from the SS to build barracks at Emalia which met the regulations. Today there is no surviving evidence of this cramped network of barracks constructed at Schindler’s expense. The Schindler subcamp employed around 900, mainly Jewish, workers, many of whom were in truth unfit or unqualified for factory work. Their food was mainly bought on the black market and, with nutrition considerably better than that of the prisoners in Plaszów, even those Schindler Jews who were later shipped to hard labour camps, such as Mauthausan, were stronger and better placed for survival. As the war drew to an end in October 1944, Schindler moved almost 1,100 workers on ‘Schindler’s list’ to the safety of a factory at Brnnec-Brünnlitz in the Sudetenland.

Since the end of the war, the factory has fallen into disrepair and become home to a series of small-scale industrial uses. It has been difficult to find, a rundown building in an edge-of-town industrial area with nothing to indicate its significance. Pressure from international and local sources to recognise the central role of the site in the survival of so many has led to some restoration work being carried out. The Ministry of Culture has funded some limited renovation, with more under way.

In 2008 it was announced that two Italian architects, Claudio Nardi and Leonardo Maria Proli, had won the tender for the design of a Museum of Modern Art on the site. In selecting the scheme the jury felt it would ‘harmonise with the atmosphere of the former Schindler factory, and respect the emotional and historical identity of Schindler’s factory. The judges appreciated the project’s minimalism, harmony, simplicity and use of clear spatial solutions and high quality materials.’ A new building, with over 4,000 square metres of exhibition space, is to be constructed. The historic road-front factory will be restored and converted into cinema facilities, a cafe and a bookshop.

The city council hopes that it will kick-start regeneration in the Krakow suburbs of Podgórze and Zablocie. There is, however, internal disagreement to this proposal from some of the city’s Law and Justice Party councillors. They argue that the building should become a Museum of the Righteous Among Nations – those non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the second world war. In 2007 the city council conducted a web-based survey on the future of the factory. It claims that 48 per cent supported the art museum alone and, while 30 per cent hoped for both an art museum and a museum for the righteous, 21 per cent opposed the principle of the art museum outright.

Visitor experience of sites in and around Krakow is often primed by the conditioning and expectation arising from both Keneally’s novel and Spielberg’s film. It led quickly to the development of ‘Schindler tourism’. It is perhaps not surprising that this story of humanity at the heart of the holocaust draws people to visit. A combination of audiences: the macabre, the curious, the respectful and the star struck. But even with the movie’s draw and a powerful story luring visitors, the places of the Schindler narrative today remain in various states of repair and preservation, and offer very differing levels of commemorative status.

The Krakow ghetto

The Krakow ghetto was established in March 1941. Jews from all over the city and surrounding area were crammed together into a few streets in Podgórze, south of the Vistula River from the main city centre. The packed ghetto area housed up to seven times its pre-war population. It was enclosed in part by walls, of which small portions still survive, shaped like rows of Jewish tombstones. In December 1942 it was divided into two areas. In March 1943 the Nazis liquidated the Krakow ghetto. Those from section A, and able to work, were marched to the labour camp in Plaszów. Those in section B, mostly women, children, the elderly and the ill, were killed in the street or transported to Auschwitz or Belzec.

Unlike some other Eastern European wartime ghetto areas, such as in Budapest, where there is a stronger sense of remembrance, the site of the former Krakow ghetto is still rather a forgotten place. Until recently there has been no major commemorative structure, just the occasional plaque. The small surviving remnants of ghetto wall are scrawled with graffiti and jostling with modern life. But in 2005 a new memorial by Piotr Lewicki and Kazimierz Latak was installed at Plac Bohaterow Getta. The 70 large bronze chairs which mark the site of the walls stand around the edge of a square, symbolising furniture and belongings being thrown out into the street at the liquidation of the ghetto.

The low public profile of Podgórze has not been helped at all by Schindler tourism elsewhere in the city. The Spielberg film used the historic Jewish Kazimierz district to portray the ghetto rather than Podgórze itself, which was considered to be too much changed by modern development. Kazimierz is within the world heritage site for Krakow’s historic centre (inscribed 1978), while Podgórze lies outside it. Kazimierz is heavily visited for its attractive old buildings and Klezmer cafes, but also as much for its film stardom and perceived, if not genuine, Jewishness.

The result was that the city made regeneration of Kazimierz a priority, and gradually a positive and prosperous air is starting to return. In Podgórze, however, still too far from the city centre for many visitors and not spared by the passage of time, the atmosphere is generally one of the rundown urban edge. Although in 2005 Steven Spielberg donated $40,000 towards the preservation of the former Pod Orlem (Under the Eagle) pharmacy, whose non-Jewish owner had remained in the ghetto to help the Jews, the Schindler effect is slow to catch on in Podgórze.

[The monument to all nationalities killed in the Plaszów forced labour camp. Designed by Witold Ceckiewicz, it was erected in 1964.]

Plaszów forced labour camp

The Plaszów camp was built in the southern suburbs of Krakow as a forced labour camp, but extended as a concentration camp under the supervision of Amon Göth, a brutal Austrian SS officer who was thought to have personally shot over 500 Plaszów Jews. The camp was on the site of the Krakowski and Podgórski Jewish cemeteries, which were destroyed along with Adolf Siódmak’s huge pre-burial hall.

Inside the Plaszów camp prisoners worked in factories and quarries. The factory owners were offered incentives of free rent and a ready source of workers to set up there. The camp held over 25,000 prisoners at one time: Jews, Poles, Romanies, Italians, Hungarians and Romanians. The dismantling of the Krakow ghettos in 1943 led to the further incarceration at Plaszów of those surviving Jews capable of working. More than 80,000 Plaszów prisoners died by the end of the war, many having been sent to the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau, but over 8,000 people were actually killed there. As the Russians advanced on Krakow in 1945, the Nazis destroyed the camp and tidied away as best they could. The bodies from the mass graves were exhumed and burned.

Today there is little to indicate the scale of operations at Plaszów or its harrowing history. It is little mentioned in guidebooks and not part of the visitor trail. A wild overgrown open space, strewn with litter, more home to dog walking than to commemoration, it is marked only by a sign at the entrance and a cluster of memorials, the largest a sculptural monument erected in 1964. Amid the scrubland few buildings survive: the foundations of some of the barracks, a cemetery building and Amon Göth’s villa, from where he was reputed to have taken pot shots at passing prisoners in the camp.

There are now plans to enhance and protect the site. The Ministry of Culture proposes to take over management and give it national memorial status. A 2007 design by Krakow-based Proxima Design Group includes delineation of the boundaries, symbolic lighting of the footprint of the camp barracks, and a footbridge over the site to protect the ground and give visitors an overview. But even this (relatively) simple scheme has caused considerable local opposition. Developers object to the proposed restrictive buffer zone that memorial status will bring; local people object to the design; and Jewish groups object to the interpretation of the site to encourage tourists and especially to placing poles into ground that contains human remains.

Auschwitz-Birkenau

The industrial town of Oswiecim, some 45 miles from Krakow, housed Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest of the six Nazi concentration and extermination camps. The original buildings on the Auschwitz I site were constructed initially as barracks, becoming a concentration camp for Poles and Soviets. In 1941 work began at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, less than two miles away. Birkenau soon became the main mass extermination camp to implement the decisions of the 1942 Wannsee Conference, the ‘final solution of the Jewish question’. In the wider area a further 40 or so sub-camps, including the chemical works at Auschwitz III, were constructed.

Although people were brought from all over Europe to Auschwitz, the first waves of prisoners were Poles, beginning with political prisoners and culminating in the shipment of large numbers of Polish Jews from the clearance of ghettos, such as the 2,000 people sent from the liquidation of Krakow in 1943. As the war drew closer to an end, further Polish prisoners were shipped to Auschwitz as the labour camps, like Plaszów, which had held them closed down.

In October 1944 the 300 women from ‘Schindler’s list’ on their way to the safety of the factory at Brnnec-Brünnlitz were deported in cattle cars to Auschwitz. There they were held for three weeks and subjected to Dr Josef Mengele’s selection of those who were fit to work and those, around 70 to 90 per cent of new arrivals, who should be sent immediately to the gas chambers and crematorium. Intervention by Schindler, either directly or on his behalf, and a good deal of bribery and use of influence, got them released and sent on to Brnnec-Brünnlitz, to the factory the men were already constructing. This was one of very few shipments of prisoners to leave Auschwitz.

[The railway into Auschwitz II-Birkenau passes under the main guard house of 1943 to the selection platform, from where many were sent directly to the gas chambers]

In 1979 the site became the Auschwitz Concentration Camp World Heritage Site. In 2007 the inscription was changed to Auschwitz Birkenau, German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940–1945).

‘At the centre of a huge landscape of human exploitation and suffering, the remains of the two camps of Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, as well as its protective zone were placed on the world heritage list as evidence of this inhumane, cruel and methodical effort to deny human dignity to groups considered inferior, leading to their systematic murder.

‘The camps are a vivid testimony to the murderous nature of the anti-Semitic and racist Nazi policy that brought about the annihilation of more than 1.2 million people in the crematoria, 90 per cent of whom were Jews’ (from the Auschwitz-Birkenau World Heritage Site Statement of Significance).

The protected structures include 150 buildings, about 300 ruins and vestiges of the original camp, including the ruins of the four gas chambers and crematoria in Birkenau. There is more than 13km of fencing, with 3,600 concrete fence posts. The 200 hectares of grounds also contain roads, ditches, railway tracks and sidings, sewage treatment plants and reservoirs.

|

|

[Left: ‘Arbeit macht frei’ (work brings freedom). The gates of Auschwitz I and the original brick barrack buildings of the first site. The camps and 39 sub-camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau covered 15 square miles.]

[Right: The partially destroyed gas chambers of Birkenau have required substantial stabilisation work to alleviate damage due to ground water conditions, structural ground pressures and a million visitors a year.]

Visitors who are not part of guided tours may wander around as they wish. There are sequences of chronology and theme which guided tours follow. The packages and tours stride purposefully around the site keeping to their itinerary. The participants meandering around drift between solemnity and a chat about what is for lunch. To stand and watch these groups of half-day trippers doing as they are bidden and being marched around a preconceived route presents a harrowing image: a metaphor of which they seem unaware.

‘The site is a key place of memory for the whole of humankind for the holocaust, racist policies and barbarism; it is a place of our collective memory of this dark chapter in the history of humanity, of transmission to younger generations and a sign of warning of the many threats and tragic consequences of extreme ideologies and denial of human dignity’ (from the Auschwitz-Birkenau World Heritage Site Statement of Significance).

Many commentators have attempted to analyse the museumisation of Auschwitz and the creation of tourist spectacle rather than the retention of history. It has been dubbed ‘Auschwitzland’. It has been called a ‘Hall of Mirrors, a half-world between history and art where the attempt to halt time…, to sidestep the processes of decay and dilapidation, involves the artful and conscious construction of illusion, the elaboration of mimetic effects which are designed to conceal themselves, in a discourse, certainly of aesthetics, and in some cases also of ethics’ (Keil 2005).

More than a million people visit Auschwitz every year. Sixty years of climatic extremes have taken their toll on what were intended often as temporary structures. Extensive, continuing conservation work has been carried out. From the end of the war, a cycle of repair and replacement has meant that timber barrack buildings have been dismantled and rebuilt regularly.

The current priorities for conservation include conserving and protecting the ruins of the gas chambers and crematoria, and a variety of wooden and brick barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau. It is proposed that 11 barrack blocks will house a new main exhibition, with five blocks left in an unaltered condition. A space for art exhibitions will be created in the kitchen area of Auschwitz I. Work has already been carried out to stabilise the gas chambers, using micropiles as the ruins had eroded and deteriorated due to ground water conditions, structural ground pressures and visitor damage. ‘Preserving authenticity is an absolute priority... The lack of permanent funding for preservation could have unimaginable consequences’ (from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Annual Report 2008). The establishment in 2008 of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation aims to create a perpetual fund to preserve the Auschwitz Memorial and implement long-term conservation proposals.

The costs of maintaining the site are spiralling out of Polish control. The Polish government contributes around £2 million a year, while a further £2 million is earned from the sales, tours and parking. The museum has applied for European Union funding of almost £5 million to support 85 per cent of the cost of major conservation projects. But it is estimated that the long-term work needed could be in excess of £50 million. Pleas have been made to the wider international community to support its preservation. But in December 2004 the Independent reported that a survey by the BBC had found that 60 per cent of people under the age of 35 had never heard of Auschwitz, and 45 per cent of all British adults did not recognise the name.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Fiona Newton, IHBC projects officer, projects@ ihbc.org.uk

References

- Charlesworth, A and Addis, M (2002) ‘Memorialisation and the ecological landscapes of Holocaust sites: the cases of Plaszów and Auschwitz-Birkenau’ Landscape Research 27.

- Cole T (1999) Selling the Holocaust, from Auschwitz to Schindler: how history is bought, packaged and sold, Routledge.

- Crowe, D M (2007) Oskar Schindler: the untold account of his life, wartime activities, and the true story behind the list, Perseus.

- Keneally, T (1982) Schindler’s Ark, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Keil C (2005) ‘Sightseeing in the mansions of the dead’, Social and Cultural Geography, Vol 6, No 4, August 2005

- Kugelmass, J (1994) ‘Why we go to Poland: Holocaust tourism as secular ritual’, in Young, J (ed) The Art of Memory: Holocaust memorials in history. Prestel-Verlag

- Memorial AuschwitzBirkenau Report 2008.

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Brutalism.

- Brutalist London Map - review.

- Charles Waldheim - Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory.

- Conservation.

- 'England's Post-War Listed Buildings'.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- James Crawford - Fallen Glory.

- Owen Hatherley - Landscapes of Communism.

- Regeneration.

- Spomeniks.

- World heritage site.

- Edinburgh world heritage site valued at over 1 billion.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?