Construction organisation design

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

The internal structure of a company is called the Organisation Design. The internal structure of the company affects its efficiency, effectiveness and ability to respond to new opportunities, which can affect the level of organisational profit.

This article discusses several organisational designs, their historical development and the advantages and disadvantages of some of the most popular designs.

[edit] Classical organisation theory

The classical organisation is most often associated with bureaucracy. The design of the bureaucracy is attributed to Max Weber and dates back to the beginning of 20th century. Weber specified what he believed was an ideal company structure. Some characteristics of Weber's ideal bureaucracy structure can be described as [107], [73]:

[edit] Positions arranged in a hierarchy

According to Weber: 'The organisation of offices follows the principle of hierarchy: that is, each lower office is under the control and supervision of a higher one.' Herbert Simon [96] identified similarities of the hierarchy design with nature and the laws of physics, when he stated: 'Each cell is in turn hierarchically organised into a nucleus, cell wall, and cytoplasm. The same is true of physical phenomena such as molecules, which are composed of electrons, neutrons, and protons.';

[edit] Specialisation

Bureaucracy is based on specialisation, power and competence. Each level of the structure has to know its competence, goals and the subjects that it is in charge of. The authority that is giving orders is very important in bureaucracies. Orders come only from this authority and not from anywhere else. Each part of the chain in the bureaucratic model knows precisely its competence in order not to conflict with things under the care of other parts of the organisation;

[edit] Impersonal relationship

Weber's believed that the ideal bureaucracy must work with impersonal relationships. To produce rational decisions it is necessary to leave out personal emotions such as passion, love, hate, etc.

[edit] Strong rules

The ideal bureaucratic company is a strong one. To achieve stability even when the personnel inside the company are changing there must be a set of abstract rules for all circumstances. This includes all of the company rules; from specifications of particular internal processes and how to accomplish them, to permits and prohibitions for employee behaviour;

[edit] Promotions

To maintain stability and give employees a feeling of safety and security there are specific rules for promotion. Promotions are made according to achievements and seniority. Older employees (in the view of time served within the company) are higher up the ladder of competency and it is almost impossible that an individual could achieve several levels of promotion at the same time.

[edit] Technical qualifications

People are employed based on their qualifications. In the ideal model it is impossible to hire engineering qualified personnel for management functions and vice versa.

Weber's model is an idealised design, a concept of theory, which was believed by Weber to be the most effective design for companies in early 20th century. However, bureaucracies were much criticised by sociologists and philosophers, including Karl Marx, for example. They suggested that bureaucracies are used primarily to control people and have strict rules, which stifle the enthusiasm and initiative of the employees.

Bureaucracies have been used for many years in many companies with many modifications to Weber's idealised model. This has produced a pragmatic evaluation of the bureaucracy concept and many scholars and management consultants, including the famous Peter Drucker and others, observed it closely and proposed modifications to the Weber's model. Warren Bennis summarised some of the bureaucracy deficiencies as follows [5]:

- Bureaucracy does not adequately allow for personal growth and the development of mature personalities;

- It develops conformity and groupthink;

- It does not take into account informal organisation or emergent and unanticipated problems;

- Its systems of control and authority are hopelessly outdated;

- It has no juridical process;

- It does not possess adequate means for resolving differences and conflicts between ranks and, most particularly, between functional groups;

- Communication and innovative ideas are thwarted or distorted as a result of hierarchical divisions;

- The full human resources of the bureaucracy are not utilised because of mistrust, fear of reprisals, and so forth;

- The bureaucratic designs cannot assimilate the influx of new technology or scientists entering the organisation;

- The bureaucratic designs modify individual personality in such a way that the person in a bureaucracy becomes the dull, grey, conditioned 'organisation man'.

.

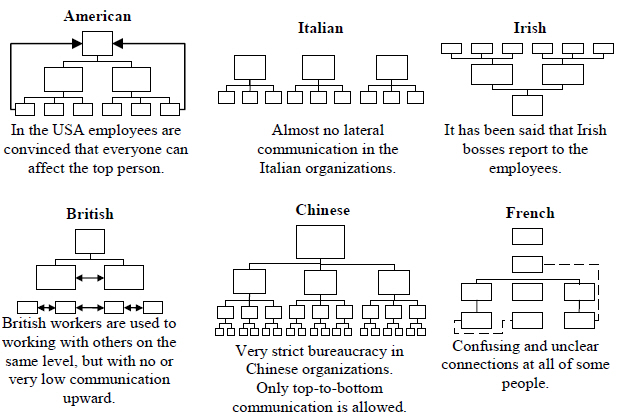

[Image source ref 73]

During many years of using the more traditional bureaucratic models in companies some modifications to the ideal model have been developed and observed. The most distinctive characteristics are centralisation versus decentralisation and tall versus flat structures.

[edit] Decentralisation

There are three alternatives for how a structure can be decentralised: geographical; functional; and by decision making:

- The main criterion for geographical decentralisation is the geographical location of the company's operations. In today's global world every international company has some level of geographical decentralisation as it has subsidiaries in many different countries. The more the company wants to expand the greater this type of decentralisation will be.

- Functional decentralisation focuses on the degree to which the functional parts of company's operations are centralised or decentralised. The company can be split into functional departments (e.g. IT, finance, marketing, human resources, etc.) but then parts of the same department can be based in the same location and centralised, or not. The company can have one IT division controlling all IT in the whole company based in one place, or every subsidiary can have its own smaller IT department.

- Decentralisation by decision making refers to whether the company has centres where decisions are made or not. It appears that the level of this type of decentralisation is bound to the level of geographical decentralisation. In companies where there are managers of each subsidiary with full responsibilities over it, the top managers in the company headquarters determine only whole-company policy and rules, but not specific tasks for the managers.

It is generally considered that decentralisation is better than centralisation. Decentralised structures increase people's autonomy. With more autonomy comes more intellectual development and the possibility of people's own realisation, bringing with it more satisfaction.

Globalisation also brings opportunities for companies to spread into other markets and build their subsidiaries in different countries, which leads to an increase in decentralisation.

[edit] Tall and flat structures

The terms 'flat' and 'tall' concern the scope of control in the company. 'In organisational analysis, the terms flat and tall are used to describe the total pattern of spans of control and levels of management. Whereas the classical principle of span of control is concerned with the number of subordinates one superior can effectively manage, the concept of flat and tall is more concerned with the vertical structural arrangement for the entire organisation [73].'

Whereas the traditional bureaucratic structure is very tall, the modern view of organisational theory tends to prefer flat structures. In fact both of have their advantages and disadvantages. Tall structures offer better control for managers of lower levels. Managers are responsible for fewer people which makes it possible to maintain stronger relations with them. The flat structure has better response to commands coming from the top because the route is shorter (fewer levels) and there is less potential for information becoming biased on its way. Flat structures also better allow individual initiative and self-control.

[edit] Modern organisation theory

Amongst the criticism of the Weber's traditional approach to organisation theory include arguments that 'Weber really did not intend for it to be an ideal type of structure. Instead, he was merely using bureaucracy as an example of structural form taken by the political strategy of rational-legal domination' [108].

As the market has progressed and evolved during the last century a new phenomenon has risen – competitiveness. With more companies in the market producing and offering substitute (or exactly) the same products, companies needed to start redesigning their structures to become more effective. Four organisational theories evolved, which constitute modern organisation theory.

- The first is to think about the company as a system of interacting parts. This concept is called the Open-System, and means that the company is interacting with its outside environment. Receiving from and sending information to the outside and acting based on this information.

- The second suggests that there is no one 'perfect' structure of the organisation. It depends on the core business of the company and on cultural aspects.

- The third approach is 'ecological'. In this approach the company is being compared to nature, where natural selection occurs. Only the sturdiest and toughest survive and in order to survive the internal structure of the company has to evolve to achieve success.

- The fourth is organisational learning '...the learning organisation is based largely on system theory but emphasises the importance of generative over adaptive learning in fast changing environments' [73].

[edit] Information processing view

The information processing view focuses on the company as a system, which receives, gathers, processes and produces information. Because there are many other similar systems outside interacting together (other companies and the environment) the organisation must deal with some degree of uncertainty. The uncertainty is defined by Jay Galbraith as 'the difference between the amount of information required to perform the task and the amount of information already possessed by the organisation' [35].

Companies need to respond to change coming from outside and adapt to survive. Tushman and Nadler [103] suggest that 'Given the various sources of uncertainty, a basic function of the organisation's structure is to create the most appropriate configuration of work units (as well as the linkages between these units) to facilitate the effective collection, processing, and distribution of information.'

Tushman and Nadler formulate the following propositions about an information processing theory:

- Different organisational structures have different capacities for effective information processing;

- The tasks of organisation sub-units vary in their degree of uncertainty;

- If organisations (or sub-units) face different conditions over time, the more effective units will adapt their structures to meet these changes in information processing requirements;

- As work-related uncertainty increases, so does the need for an increased amount of information, and thus the need for increased information processing capacity;

- An organisation will be more effective when there is a match between the information processing requirements facing the organisation and the information processing capacity of the organisation's structure.

Because of the increasing competitiveness of companies in the market, managers started to look for new, better organisational structures. In the last fifteen years of the 20th century some widely recognised organisational structures have developed and been successfully applied:

[edit] Project designs

The modern trend in business is to supply services rather than just goods. The specialisation of companies means that they are focused on their core business and for support services they need complementary services from appropriate partners. The complete service (one-stop-shop) includes a large number of activities for the supplier. A 'complete service' could be treated as project management. The company needs to manage the whole business cycle from communicating with the customer and specifying what they need, through making or developing a product, to delivering and maintaining it.

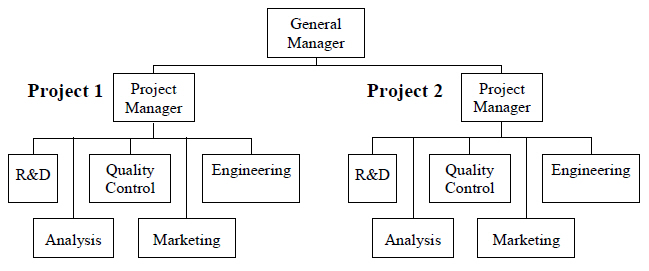

Moreover, the company can have many simultaneous projects producing different types of outputs, in contrast with the classical company structure where the company produces only centrally specified types of outputs. In this form of company it is not possible to centrally plan what each unit will do because each project needs something different. To aid this business strategy the project design structure has appeared.

Note that both projects are using the same units (departments) of the company, but for different purposes. This is typical, but for specific purposes there is a modification of this typical project structure.

The other thing that is needed if the company wants to adopt a project design structure is different styles of management. Change happens all the time, everywhere. This requires dynamic activities to successfully manage the whole structure. The managers must become reoriented to the management of human resources rather than strict, functional rules. Good relations between each of the project groups are crucial for achieving effectiveness. The project structure is a concept of management and not only a form of structural organisation.

[edit] Matrix designs

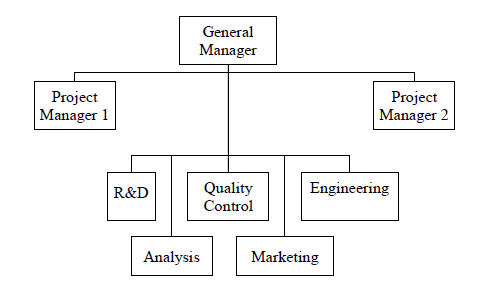

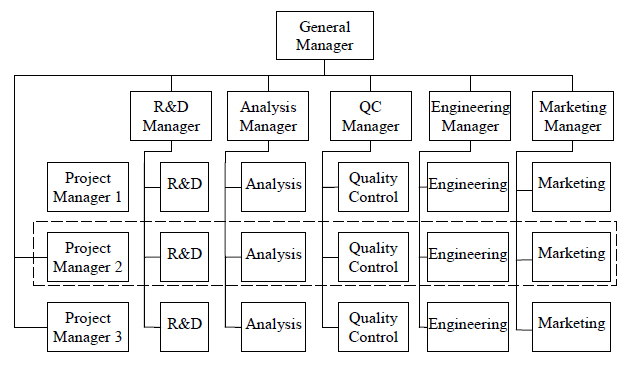

A matrix structure is one of the most applied organisational structures. A matrix structure is a combination of functional and project organisational forms.

In a matrix organisation, each project manager reports directly to the general manager (in large companies there could be more levels). Since each project represents a potential profit centre, the power and authority used by the project manager comes directly from the general manager. The project manager has the total responsibility and accountability for the success of the project. The functional departments (such as R&D, etc.) have functional responsibility to maintain technical excellence on the project. Each functional unit is headed by a functional manager whose prime responsibility is to ensure that a unified technical base is maintained and that all available information can be exchanged for each project.

The main difference in the matrix structure is that the same unit is used by many projects. It is up to project managers who will do what and when. Observation of companies utilising matrix structures shows that '[...] because of the amount of interaction among members in matrix structures, and the high levels of responsibility they possess, matrix organisations usually have greater worker job satisfaction' [93].

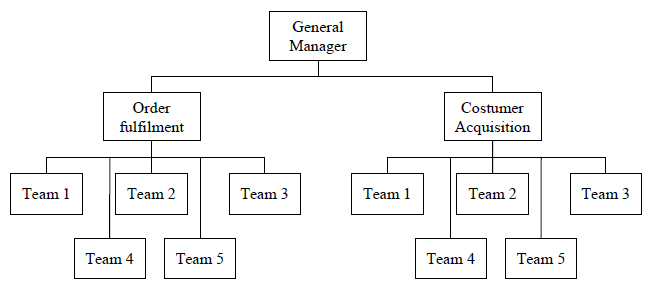

[edit] Horizontal designs

Currently the “customer-driven” approach is recognised as the 'correct way' for companies to evolve. Horizontal organisations consist of teams which are organised around business processes rather than functional departmentalism. The teams are responsible for the results they generate. They are measured and people are rewarded according to team results, not individual performance. This approach leads to a better focus on the task rather than individual specialisations.

In order to be a successful horizontal structure, all employees need to be fully informed and trained. Communication between and inside the team is crucial. People should be provided with full data, not just some parts, and in conjunction with this information an ability to interpret it to produce better decisions.

Also typical is direct contact between team members and suppliers or customers. This produces less bias in information than if they were going through many layers of the organisation and makes it possible to react quickly to customer's requirements or problems.

As stated in Byrne [15] many American international companies like AT&T, Motorola, GE, Xerox and others have adopted the horizontal structure to increase their effectiveness.

[edit] Virtual organisation

Virtual organisations have emerged as a response to environmental change, which demands quick, cheap and quality solutions. One definition suggests: 'A virtual organisation or company is one whose members are geographically apart, usually working by computer e-mail and groupware while appearing to others to be a single, unified organisation with a real physical location.' [109]. Another more target-oriented definition says: 'The virtual organisation is a temporary network of companies that come together quickly to exploit fast-changing opportunities.' [73]

In other words it could be described as a large alliance of companies connected together by modern information technology, with different backgrounds but focusing on the same goal. This collaboration gives companies competitive advantage in the market which they are not able to achieve alone. According to [12] and summarised in [73] the key attributes of virtual organisations are:

- Technology: Informational networks help far-flung companies and entrepreneurs to link up and work together.

- Opportunism: Partnerships will be less permanent, less formal, and more opportunistic. Companies will band together to meet all specific market opportunities and, more often than not, fall apart once the need evaporates;

- No borders: This new organisational model redefines the traditional boundaries of the company. More cooperation amongst competitors, suppliers, and customers makes it harder to determine where one company ends and another begins;

- Trust: These relationships make companies far more reliant on each other and require far more trust than ever before. They share a sense of 'co-destiny', meaning that the fate of each partner is dependent on the other;

- Excellence: Because each partner brings its core competence to the effort, it may be possible to create a 'best-of-everything' organisation. Every function and process could be world-class – something that no single company is likely to achieve alone.

[edit] Business clusters

Even though a business cluster is not an organisational structure in its true sense it still belongs to some part of organisational theory. A business cluster 'consists of several enterprises that have entered into a formal, continuing association in order to pursue some activities in common and derive maximum benefit from such synergy [105].' This closely resembles the definition of a virtual organisation. There is a tendency for companies of a similar kind in a specific region to do business in close cooperation.

These associations then bring their members a number of advantages; specialisation, lower costs per unit, better access to raw materials, production savings and bilaterally useful cooperation with institutions (universities, research institutes, consultant companies, etc.) and, very importantly, support of local governments.

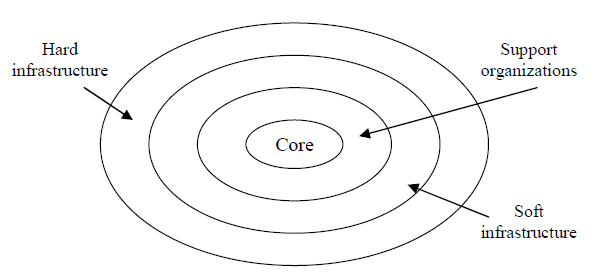

The business cluster's structure is usually composed of:

- Core businesses: The businesses that are the lead participants in the cluster, often earning most of their income from customers who are beyond the cluster's boundary;

- Support businesses: The businesses that are directly and indirectly supporting the businesses at the core of the cluster. These may include suppliers of specialised machinery, components, raw materials; and service firms including finance / venture capital, lawyers, design, marketing and PR. Often these firms are highly specialised, and are physically located close to the core businesses;

- Soft support infrastructure: In a high performance cluster, the businesses at the core and the support businesses do not work in isolation. Successful clusters have community-wide involvement. Local schools, universities, polytechnics, local trade and professional associations, economic development agencies and others support their activities and are key ingredients in a high performance cluster. The quality of this soft infrastructure, and the extent of teamwork within it, is a very important key to the development of any cluster;

- Hard support infrastructure: This is the supporting physical infrastructure: roads, ports, waste treatment, communication links, etc. The quality of this infrastructure needs to at least match competitive destinations, be they local or further afield.

To sustain competitive pressure from many companies in the market they need to systematically gather information about their rivals and based on that information make decisions. Gathering information is sometimes a problem for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), not only for financial or personnel reasons, but also because SMEs may not know what they want to find out or they do not have enough time for detailed analysis.

It is therefore logical, that in this kind of situation, companies can group to form a cluster and dispense tasks across members. It also then becomes possible to support a system, which is fully or partially automated for finding, sorting and analysing information in a particular area.

See also: Types of construction organisations.

The text in this article is based on a section from 'Business Management in Construction Enterprise' by David Eaton and Roman Kotapski. The original manual was published in 2008. It was developed within the scope of the LdV program, project number: 2009-1-PL1-LEO05-05016 entitled “Common Learning Outcomes for European Managers in Construction”.

It is reproduced here in a slightly modified form with the kind permission of the Chartered Institute of Building.

--CIOB

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Business administration.

- Business model.

- Business process outsourcing (BPO).

- Consortium.

- Contingency theory.

- Environmental scanning.

- Limited company.

- Limited liability partnership.

- Joint venture.

- Office manual.

- Organisation design.

- Partnering and joint ventures.

- Personal service company.

- Special purpose vehicles.

- Succession planning

- Types of construction organisations.

[edit] External references

- [5] Bennis, W.: Beyond Bureaucracy. Trans Action July-August 1965.

- [12] Business_Week: The Virtual Corporation. Business Week February(8): 98-102 1993.

- [15] Byrne, J., A.: The Horizontal Corporation. Business Week December(20): 78-79 1993.

- [16] Christie, P., R. Lessem, i in.: African management: philosophies, concepts, and applications. Randburg, Knowledge Resources 1993.

- [35] Galbraith, J. R.: Designing complex organizations. Reading, Mass., Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. 1973.

- [73] Luthans, F.: Organizational behavior. Boston, Mass., Irwin/McGraw-Hill 1998.

- [93] Riggio, R. E.: Introduction to industrial/organizational psychology. Glenview, Ill., Scott, Foresman/Little, Brown Higher Education 1990.

- [96] Simon, H. A.: The new science of management decision. New York, Harper 1960.

- [103] Tushman, M., D. Nadler: Information Processing as an Integrating Concept in Organization Design. Academy of Management Review July: 614-615 1978.

- [105] Vernon, P.: The language of business intelligence. Pobrano 16 maja 2007 r. z 2004.

- [107] Weiss, R., M.: Weber on Bureaucracy: Management Consultant or Political Theorist? Academy of Management Review Kwiecie: 242-248 1983.

- [108] Whatis.com: IT dictionary - Virtual organization. Pobrano 16 maja 2007 r. z http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/0,,sid9_gci213301,00.html 2007.

- [109] Wikipedia_CZ: marketing z http://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marketing.

Featured articles and news

UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard V1 published

Free-to-access technical standard to enable robust proof of a decarbonising built environment.

Prostate Cancer Awareness Month

Why talking about prostate cancer matters in construction.

The Architectural Technology podcast: Where it's AT

Catch up for free, subscribe and share with your network.

The Association of Consultant Architects recap

A reintroduction and recap of ACA President; Patrick Inglis' Autumn update.

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.