6 Burlington Gardens

At 6 Burlington Gardens, London, the Royal Academy of Arts has reawakened an unloved Victorian building and connected it with the RA’s old home at Burlington House.

|

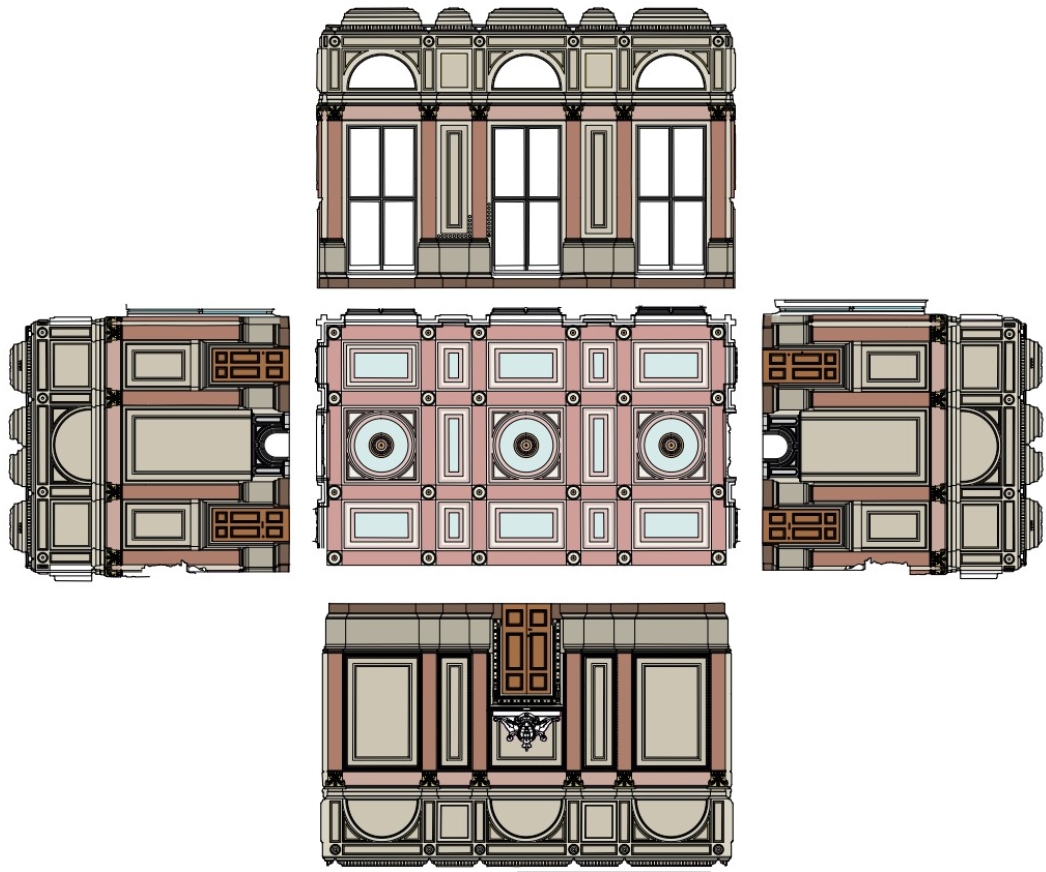

| The decorative scheme for the Central Senate Room. |

Contents |

Introduction

2018 marked the 250th anniversary of the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts. On 19 May, the RA opened the doors of 6 Burlington Gardens to invite in the public after an ambitious project that had been in the making for 10 years. This reawakening of an old, unloved Victorian building and its interconnection with the RA’s old home at Burlington House has significantly improved a number of the principal historic spaces while introducing new contemporary interventions informed by the original architecture.

6 Burlington Gardens was originally designed by James Pennethorne in 1866 as the University of London’s Senate House. The north elevation presents itself as a grand classical public building with ornate detailing in homage to Burlington House, while the rear elevation is essentially brick and more utilitarian in character. Pennethorne decorated the main facade with figurative sculpture representing famous figures in science, literature, law and medicine, representing the humanist, liberal-minded aspirations of the university. The original building once accommodated a three-storey-high lecture theatre and a double-height library. The university relocated in 1899 and subsequent modifications to the fabric occurred to accommodate its later inhabitants. Significantly, Pennethorne’s original lecture theatre and library were stripped out to create new offices for the Civil Service Commission, and further works undertaken in the 1920s created a suite of interiors for the first home of the British Academy.

The RA purchased 6 Burlington Gardens in 2001 with the intention of expanding into the space. The state of the existing building and physical separation from the RA’s Burlington House were key issues addressed by the master plan that commenced in 2009. The master plan led by David Chipperfield Architects (DCA) resolved the connection of the site by proposing a new public route from Burlington House, through the former art-handling areas, into the schools and rising up with a new link bridge to the raised ground-floor level of 6 Burlington Gardens. The creation of a lecture theatre was a major aspiration of the RA for their new building and it made sense to reinstate a theatre in the location of Pennethorne’s original, despite the consequences to the British Academy interiors.

The master plan sought to unlock the sequence of first-floor rooms of 6 Burlington Gardens and to create an H-shaped plan of circulation space, reflecting the original circulation of the ground floor. The first-floor southern rooms, which were originally laboratories, lent themselves naturally to top-lit galleries but needed to be brought up to modern standards. The intention for the Senate Rooms, the most grand and decorative spaces within 6 Burlington Gardens, was to allow them to be used as public spaces where they could achieve a wider appreciation. The proposed work was a careful balance of restoration, alteration that was necessary to facilitate the new use and thoughtful integration of services.

The fundamental principles of the master plan were upheld during the detailed design phase with the overarching principle of the restoration works that the building should be preserved and restored in part with the interventions clearly identifiable, while being cautious not to over-restore. 6 Burlington Gardens had been a hard-working building, and the patina and wear reflect that. Now complete, the project has delivered a sequence of spaces that not only increases the floor area and facilities in the RA but also enhances their role in the making, displaying and understanding of art. The completed works have created some memorable interiors of exquisite design, carefully balancing intervention and retention.

Lecture theatre

The new lecture theatre is a good example of the strategy towards the modern interventions. It was not only logical to reinstate the lecture theatre in the location of the original but was also acknowledgement of Pennethorne’s initial layout. Excellent drawings and images of the original design survived but faithful reinstatement of this would not have been possible. The original worked to tighter space standards with no level access and passive thermal and acoustic controls that would fall short of the high-performance specification requested by the RA. Despite this, the original layout influenced DCA’s design of the new: the lecture theatre ‘bowl’ sitting within classically detailed walls and the horseshoe-shaped seating arrangement were features of the new design.

During the 1900s a new floor had been inserted into the space and unpicking this arrangement was complicated, but much of the first-floor internal wall elevations survived, as did the decorative plastered ceiling. Historically there had been movement of one of the principal timber trusses over the space and the structural engineer Alan Baxter Associates specified supplementary strengthening to resolve this. JHA specified the careful repair to the plasterwork and historic fabric, where it had been damaged. The completed interior is an elegant, understated modern interior within a historic framework.

British Academy Room

One of the most complex elements of the restoration works was the dismantling, relocation and repair of the British Academy Room, a survivor of the British Academy’s occupation of the eastern portion of 6 Burlington Gardens from 1928. Although being contemporary with the art deco period, Arnold Mitchell’s design reflected Britain’s reluctance to fully depart from the classical past. The architecture of the room had more in common with classical design than the modern movement. However, modern fashion did influence elements of the design, such as the restrained wall panelling of vast sheets of exotic hardwood veneer and the green onyx fireplace. In relation to the master plan, the British Academy Room physically prevented the re-establishment of a lecture theatre within the east wing of the building. This issue was carefully debated. The decision that emerged was that the British Academy Room was of such high quality and significance that it should be carefully dismantled and relocated into a new purpose-built extension in the south-east corner of the building.

With our knowledge of historic interiors we anticipated that the process would be relatively straightforward. Similar work had been done before, but as anyone who has experience in the dismantling or repair of buildings knows, there will always be unexpected issues which come back to haunt the heritage architect. Equally, there can also be wonderful discoveries, which illuminate how the building was constructed with the marks of the people involved.

Specialist joiners from Fullers Builders methodically took the panelling down in sections, as large as possible, to allow handling and transportation. The panelling, fireplace, windows and marble shelves were removed relatively easily, but the plasterwork proved more complex. The ceiling was composed of fibrous cast elements and in situ plaster. We had anticipated that the small dome area of the ceiling may have been completely fibrous, but discovered that it was wet plaster on expanded metal lath over timber formwork. The plain areas of the ceiling were also largely fabricated in this way and simply carving up the ceiling into sections would not be so straightforward. As an insurance policy Artisan, the specialist plaster workers, took moulds of all the decorative elements, in case they were damaged during the dismantling process. The decorative areas were then carefully cut out from the backing plaster and safely packed away for storage while the new south-east extension was built.

Within the concrete shell of the new build, an elaborate formwork frame was constructed to support the repositioned ceiling. The plain flat areas were recreated by in situ wet plaster, with original decorative elements including the cornice and sunburst ceiling reinstated in their relative positions. The skill of the specialist plaster worker was outstanding. The panelling was re-erected on new grounds, and the restored fireplace and marble cills reinstated by Taylor Pearce Conservation.

On completion of the works, the biggest compliment on the recreation of this room came from an RA staff member who thought they were standing in the original British Academy Room.

North elevation

The principal north facade was in poor condition. Issues affecting the stonework included extreme blackening from the atmospheric pollution of the late Victorian period; calcium sulphate attack of the sandstone; contour scaling; organic growth; corrosion of iron fixing cramps; bird soiling; and missing elements of the decorative stonework and sculptural elements. We carefully specified the restoration and cleaning working closely with the sub-contractor PAYE on site to achieve the restoration. Following the strategy of retaining some of the patina and wear, the exterior was not over-restored or excessively cleaned.

For example, not all elements of the decorative frieze were put back if they were found to be missing, but important key elements were repaired and reinstated where they were prominent features, particularly on the sculptures, such as Milton’s pen and Harvey’s nose. The completed works have dramatically enhanced the building, like lifting a vale from its face. The restored surface highlights the quality of the original carved work and hopefully stimulates a reappreciation of the RA’s new entrance.

JHA worked closely with DCA to find an acceptable way to modify the portico and provide level access that would cause minimal impact on the historic north elevation. After many proposals a solution was developed which levelled the raised platforms of the portico and created a ramp in Portland stone on the east side of the building, and constructed a new ramp within the eastern circulation corridor that reached the raised ground floor. The success of this ‘landscaping’ solution has created an elegant plinth that not only overcomes the access issue, but also enables the public to sit and admire the building and the changing sculptures exhibited on the exterior.

Senate Rooms

Located on the piano nobile, the three front rooms form a suite of spaces where the University Senate once met, hence becoming known as the Senate Rooms. As the design of the building evolved it was proposed that these spaces would be used as a cafe and new dedicated architecture gallery. Within these rooms careful repairs were undertaken with subtle modifications, such as the conversion of two former cupboards into doorways and the sensitive location of services. An early decorative scheme dating from 1901 was present on the Central Senate Room ceiling, and the second decorative scheme by the Civil Service Commission was reinstated to complement the period of the ceiling.

During construction, the condition of areas of the plastered ceiling caused concern. The large blue-and-white panels displayed a plethora of cracks and movement that meant intervention would be necessary. Despite the remarkably detailed drawings produced by Pennethorne, the construction of the plasterwork was unknown. The first step was to use a borescope to help understand the fixing details. Unfortunately, this proved inconclusive. The next procedure involved sensitive opening-up work. With surgical accuracy, the plaster workers removed the central rosettes and created two inspection holes in the plain areas of the ceiling.

Remarkably, it was discovered that the decorative fibrous panels measuring 1 x 2metres (each panel) were not mechanically fixed to the ceiling construction above nor supported by material wadding. The decorative panels simply spanned between the structural beams of the ceiling. New timber grounds and new mechanical fixings could therefore be installed in four of the panels before the original decorative rosettes were reinstated. Although we had not planned to touch the 1901 decoration, strengthening work required careful touching in by a specialist decorator. This was not part of the original project, but it demonstrates the RA’s commitment to care for the building and its future.

The restoration and unification of 6 Burlington Gardens with Burlington House marks a momentous stage in the life and development of the Royal Academy of Arts. It is the biggest alteration to its estate since Sydney Smirke’s extension in the 1860s. The extended space provides a wonderful new experience to be enjoyed by the visitor.

|

| The north facade portico of 6 Burlington Gardens. |

This article originally appeared as ‘Royal Academy’s art of reconnection ‘ in IHBC's Context 157 (Page 49), published in November 2018. It was written by Lyall Thow, a partner with Julian Harrap Architects.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?