Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings

A back-to-basics approach to building services in restoring the world’s first iron-framed building will enable Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings to thrive as a workplace in the 21st century.

|

| The slender cast-iron frame of the Main Mill. |

Contents |

Introduction

Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings is the world’s first iron-framed building and forerunner of today’s skyscrapers. One of the most important buildings of the industrial revolution, it reflects a time when Shropshire led the way in engineering. Abandoned and derelict for 30 years, restoration work is now taking place to save this remarkable industrial building and to bring the site back into use as a centre for culture and creative industries.

The Flaxmill was built at Ditherington in 1797, next to the newly constructed Shrewsbury Canal. It was famed for its ‘fireproof construction’. The site developed rapidly and prospered as a steam-powered spinning mill for nearly 100 years. More than 800 men, women and children were employed, manufacturing linen thread from flax, until the demand for textiles declined and the mill closed in 1886.

The exceptional importance of the site in the industrial revolution and in world architecture is underlined by not only the world’s first iron-framed building in the Main Mill, but also by a number of other very early iron-framed buildings. There are eight listed buildings on the site, all on the heritage-at-risk register.

The buildings stood empty for a decade until the Flaxmill reopened to produce malt for the brewing industry in 1897. It was used as a barracks during both world wars and finally closed as a maltings in 1987. The buildings fell into disrepair and the complexity of the site made it difficult for potential developers to secure funding. Concern about the deterioration of the buildings grew until Historic England stepped in to purchase the site in 2005.

Conservation master plan

Since 2005 Historic England has worked in collaboration with a number of partners, including Shropshire Council and the Friends of the Flaxmill Maltings. The appointed design team, including architects Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, structural engineers AKT II and building services engineers E3 Consulting Engineers developed a master plan in 2010, comprising a combination of commercial, interpretation, community and residential uses.

The scheme was successful in gaining planning and listed building consent in 2010, and Heritage Lottery funding in 2012. The project is now being delivered in phases, which started with the office and stables buildings, which have been restored and opened as a visitor centre in 2015. Structural and envelope repairs to the Main Mill building followed and were completed in December 2018. The roof restoration included around 15,000 new Welsh slates, and more than 30,000 handmade, oversized bricks were made by Northcot Brick Limited to repair the walls.

The next phases of work involve delivering an exhibition and cafe on the ground floor of the Main Mill, and four floors of commercial space on the upper levels. The adjacent kiln will have structural repairs and a new roof, and will be converted into a spectacular entrance and vertical circulation space to gain access to the upper floors of the Main Mill. The design of the kiln will facilitate access to the Cross Mill and warehouse, enabling them to be developed in future phases. Structural and fabric repair work will continue through 2019, and the building services fit-out will follow in 2020. A new car park will be constructed in a wedge of land between the listed buildings and the adjacent railway line.

|

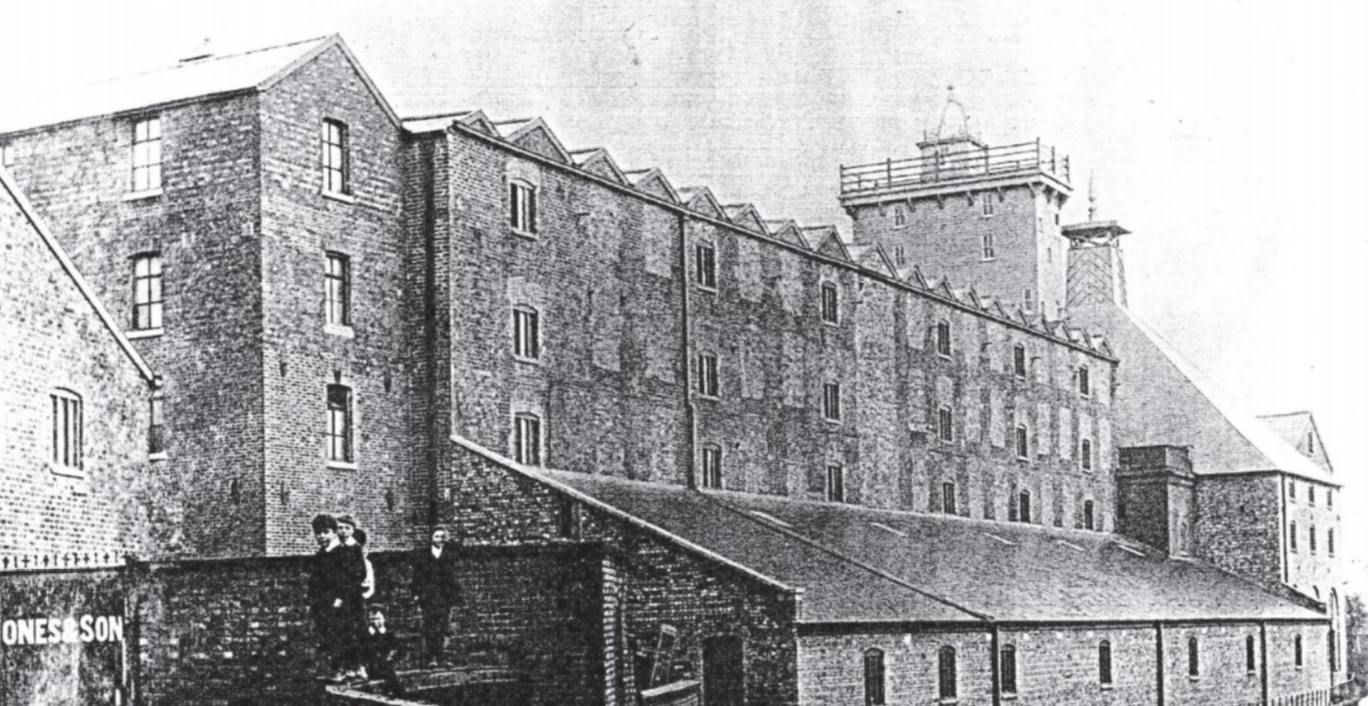

| A historic photo of the Main Mill (Photo: Shropshire Archives) |

Mechanical and electrical design

The main philosophy underpinning the design of the mechanical and electrical systems for the project is to maximise the flexibility of the building for future occupants. The future end-users of the Main Mill building are yet to be identified, and the ultimate use of other buildings such as the Cross Mill and warehouse is speculative at present.

The Main Mill building is well suited to a commercial use. The newly re-introduced Flaxmill-sized windows provide excellent natural daylight, and the windows have been detailed with sufficient free area to provide natural cross-ventilation along the floorplate. The design allows future tenants to install partitions to create cellular workspaces and meeting rooms, using sound-attenuated air-transfer paths through the partitions to maintain the ability for wind-driven cross-ventilation. E3 Consulting Engineers has carried out daylight and thermal simulation to test the design approach for a number of different potential fit-out options.

The approach for the kiln is to create an atrium-style circulation space which will be covered but unheated, akin to a railway station. Here the focus is to provide ventilation through the limited facade openings and to introduce a glazed roof lantern to allow natural daylight to penetrate down through the space. Cost efficiency has been a key driver for the project, given the limited budget available from funding bodies, the risk profile of the scheme, and the long duration on site. As a result, the design has focused on simplicity, using known and reliable technologies that are affordable to operate and maintain.

Constraints

As with many heritage projects, the buildings have a number of constraints that the design has needed to work around. These include:

- Architectural: The building has solid concrete floors, solid masonry walls and exposed vaulted jack arches throughout. The Main Mill has a grid of cast-iron columns at near-regular three-metre spacings. With no opportunity to introduce raised access floors or a ceiling distribution zone, this means that all services will be exposed to view.

- Structural: The original cast-iron frame is delicate by modern standards and the structural strategy for the scheme has placed a number of limitations on the services strategy. For example, the use of gas is forbidden within the open-plan structure of the Main Mill in order to eliminate any explosion risk that may compromise the structure in an emergency. In addition, there is a limitation on the size of penetrations that are permitted through the main service risers in the building.

- Historic: The listed nature of the buildings introduces a number of limitations, particularly in relation to penetrations through the facades for ventilation systems. Coupled with the limitations on penetration sizes in risers, this has led to a strategy of local ventilation systems with carefully placed exhaust louvres to minimise the visual impact on primary elevations.

- Phasing: The phased nature of the project has introduced several constraints, especially given the unknown future uses of other buildings around the site.

Proposed strategy

The buildings will be heated using natural gas. This is contrary to the original master plan aspiration, which was for a distributed district heating system using both biomass and gas CHP engines. However, once it became apparent that the development would be phased over a number of years and the economics of the district heating system were appraised, it became clear that the focus should be on local heating systems on a building-by-building basis. The main heating plant will be situated in the former engine house at the south end of the building, which is structurally robust enough to permit the use of gas appliances. Efficient condensing boilers have been specified and pipework will be distributed at skirting level throughout the main mill, serving floor-standing gilled tube radiators.

Ventilation will be primarily natural using opening windows, with local extract systems to WCs designed within the structural constraints described earlier. The cafe’s kitchen ventilation plant will be hidden from view within a mezzanine plant area and the exhaust will rise to roof level. A basement undercroft below the south engine house will be used to incorporate a mains water storage tank and booster set, to provide adequate pressure to WCs on the upper levels.

The main incoming power supply will come from a new substation in the proposed car park to a switchroom located in the heart of the kiln. A network of sub-main panels and distribution boards will allow all areas to be separately wired and metered. Within the Main Mill floors, perimeter trunking will be installed to provide wiring routes for tenants to fit out the floor plates. A strategy of floor-mounted lighting is proposed to provide flexibility for a multitude of fit-out scenarios without introducing a grid of suspended luminaires that may compromise partition locations.

This article originally appeared as ‘Servicing an 18th-century skyscraper’ in IHBC's Context 159 (Page 14), published in May 2019. It was written by Hugh Griffiths, a partner at E3 Consulting Engineers, who has been the lead mechanical design engineer at Ditherington Flaxmill since 2009.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?