Coal holes, pavement lights, kerbs and utilities and wood-block paving

This article originally appeared as ‘Iron, glass and wood underfoot’ in IHBC’s Context 152, published in November 2017. It was written by Rob Cowan, editor of Context.

The modern urban floorscape is littered with the dull covers of utility hatches, so it is a delight when something underfoot tells of a place’s history.

Contents |

Coal holes

|

| Coal holes. Photo by Rob Cowan, editor of Context |

Many terraced houses of the 18th and 19th centuries had one of more vaulted coal cellars under the pavement (accessed from the ‘area’, the lightwell between the street and the basement) or under the house steps. Coal was tipped from the sack through a coal hole in the pavement or steps. The coal hole was closed by a cast-iron cover. They are not manholes: their size (usually around 30–36 centimetres in diameter) is deliberately too small for a person to pass through. They usually have a raised pattern or lettering to make them less slippery in wet weather.

Some have lettering advertising the company that made the cover, or describing the cover’s special feature. Some have ventilation holes (at one time it was thought that damp coal gave off dangerous fumes), some of which have since been closed by cement. Some are inlaid with glass (sometimes in the form of prisms) to light the vault below. Some, advertised as ‘non-slip’, are inlaid with concrete.

Any text is usually in a sans-serif face (thus avoiding fine detail that might be difficult to cast), the type being appropriately tough-looking for letters made in iron and suffering harsh treatment underfoot. A few use a serif (or semi-serif) face.

Most coal-hole covers are circular, one advantage of a circular cover being that it cannot fall through its own hole. Most sit in an outer iron ring, of which many of those made by Hayward Brothers bear the words ‘This ring to be fixed with Portland cement’. A few covers are square.

Some covers are noticeably more worn than their neighbours, either because they were outside a building that was particularly heavily visited over the years, or because the iron used for the casting was rather soft.

In any particular street there is likely to be a variety of designs and makers. This may be because some of the covers have been replaced over the years after having been stolen or broken, or because the many different builders who built the street over a period of several years chose different suppliers.

Some makers of coal-hole covers are well represented in a particular place. Many of the ironfounders were very local, with an address within a couple of miles of where the coal-hole cover was fitted. For example, the builder’s ironmonger and glass-merchant Alfred Syer, which had premises in Pentonville Road from the 1830s to the 1960s, dominated the Islington market. By contrast, coal-hole covers made by Hayward Brothers (whose huge factory, pictured in its advertisements, was in Southwark) are found in many parts of London, and more widely afield.

A few manufacturers may be represented by only a single surviving coal-hole cover. In Granville Square, Islington (the model for Riceyman Steps in Arnold Bennett’s eponymous novel) there is one cover (partly obscured by cement) made by the Pantametallurgicon company of Sloane Street, Knightsbridge. No other example of a cover by this company seems to exist. Pantametallurgicon means ‘manufacturer of everything metal’. Imagine the scene. ‘What shall we call the company?’ ‘Pantametallurgicon?’ ‘Perfect!’

That company seems to have been short-lived. It is not known whether the existence of a Pantametallurgicon company in Melbourne, Australia, advertising ‘gasaliers… these massive and elegant gasfittings’ and ‘No more leaking roofs now the Pantametallurgicon is open: Galvanised Corrugated Iron, best brands only, 3d. Per Foot’ in 1877 was evidence of the company, or just the name, jumping continents.

Back in England, an advertisement for Hayward’s Patent Safety Coal-hole Plate in 1868 quotes prices. The smallest (12-inch diameter) costs 2/9 in solid iron; a ‘ventilating plate’ (with holes) costs three shillings in that size; and an ‘illuminating plate’ (with glass) six shillings.

The advertisement explains the special qualities of the safety plate. ‘The ordinary coal-hole plate is often the cause of serious injury, from its shifting and turning up when trodden on, after the stone into which it is let has become a little worn; it is easily raised from above, and placed partly on one side, either for mischievous or worse purposes. Both these objections are quite overcome by the flange in the “Safety Plate”, which renders it impossible for the plate to turn on one side until it has been raised in a perpendicular direction for more than two inches, and this cannot take place until released from below, as the play of the chain or hook could never exceed half an inch.’

There is a generic term for coal-hole covers: opercula, borrowed from biological terminology (operculum, Latin for a cover or lid, describes features such as that covering the gill of a fish) by Shephard Taylor. As a medical student in the 1860s Taylor developed a passion for coal-hole covers, making (and later publishing) drawings of hundreds of them, although he left out the lettering. Best known among modern enthusiasts for coal-hole and utility covers is Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, who photographs them on his mobile phone.

Today some covers still sit in their original paving stone; in some cases that stone has been preserved reset in more modern paving; and in other cases the coal-hole cover itself has been reset in concrete or asphalt paving. Covers are at risk of being taken up, stolen, damaged, or buried under asphalt or concrete. That is why it is important to make people aware of the history under our feet.

The Georgian streets of London’s Spitalfields retain a good number of historic coal-hole covers. There are also some examples there of what look like modern versions. In this case the circular metal plates set into the pavement were inspired by the coal-hole covers but are purely decorative. They were designed by the sculptor Keith Bowler, working to a 1995 commission from Bethnal Green City Challenge. The designs reflect Spitalfields’ culture and history: the themes include the match girls from the Bryant and May factory (celebrated for their 1888 strike); the clothing industry (represented by scissors and buttons); and silk weavers (represented by a weaver’s shuttle and reels of thread).

While coal-hole covers are the most locally distinctive, there is interest to be found in other metal covers to utilities below the street. People who have a particular fascination for them call themselves ‘gridders’. The lettering that some of these artifacts bear provides a historical record of the companies or authorities that made or installed them. Elsewhere, in Norway, Denmark and (often garishly coloured) in Japan, for example, the potential of utility covers for municipal self-expression has been vividly exploited.

Pavement lights

|

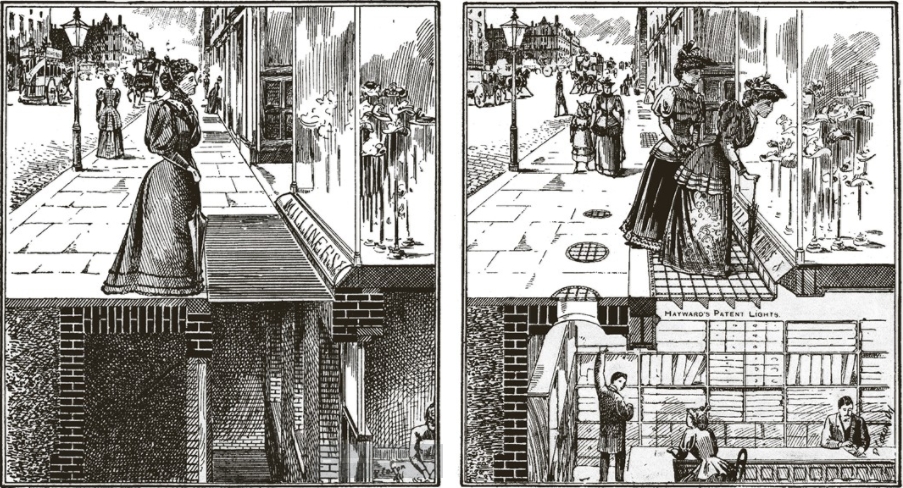

| The benefits of pavement lights, from a 1890s Hayward Brothers and Eckstein catalogue. |

In the 19th century the manufacture of pavement lights for commercial premises became big business. Replacing open gratings, they allowed light into basement rooms, while providing a walkable surface at street level and keeping out the rain. In the mid-19th century pavement lights were made of blocks of glass set in a metal fame. Notches in the metal, and often the raised lettering with the maker’s name, made the surface less slippery for people passing along the street.

In the 1870s Hayward Brothers, the company we have already come across as London’s largest manufacturer of coal-hole covers, introduced an innovation in its pavement lights. In addition to simple glass blocks (the cheapest option), they offered lights glazed with bull’s-eye lenses, semi-prisms and prisms, the last being the most expensive and the most effective in reflecting the light to where it was most needed. Later pavement lights were (and are) made of glass set in reinforced concrete, under brand names such as Luxcrete.

By the 1890s Hayward Brothers and Eckstein (as the company had become) published a catalogue devoted to pavement lights and similar products running to 73 pages. It quotes a testimonial by the department store Marshall and Snelgrove: ‘Our basement is lighted by Hayward’s Patent Pavement Lights, the daylight being thrown 30 feet back, enabling the space to be utilised as counting-house, &c.’

Two illustrations in the catalogue show the value of pavement lights. In the first, a well-dressed lady gazes at the window of a hat shop, unwilling to risk compromising her modesty by standing on the open grating that lies between her and the window. In the second, a Hayward’s pavement light has been installed, allowing the woman to come right up to the shop window, and transforming the formerly gloomy basement below into a well-lit workspace.

Another leading manufacturer of pavement lights was Hyatt, founded by the New York inventor and slavery abolitionist Thaddeus Hyatt (1816–1901), who spent the latter part of his life in England.

Many historical pavement lights remain, some in good condition, others worn or decayed. The glass may be cracked or missing, and is sometimes discoloured to a purple by years of ultra-violet light.

Traditional metal pavement lights (and reproductions of originals) are still made. In recent years, for example, a series of large circular pavement lights replaced originals above the basement of the Drapers Hall livery company in the City of London.

Kerbs and utilities

|

|

Left: Cast-iron kerbs in Manchester. Photo by Rob Cowan, editor of Context. Right: Thomas Crapper set up his business in 1861 but, contrary to popular belief, his name was not the origin of the slang word (photo of a cover in Westminster Abbey by Robert Huxford). |

Other iron on the street surface is seen in the form of cast-iron kerbs. Examples of these remain in Bristol (where they are particularly characteristic), Edinburgh, Ironbridge, Manchester and Shrewsbury, among other places. In most cases they are relics of a time when iron was locally cheaper than stone.

Metalwork of interest is also found in utility covers that tell us something about the history of the place, such as those that bear the names of former local authorities or other barely remembered organisations.

Wood-block paving

|

| A short stretch of woodblock paving in Chequer Street, Islington. Photo by Rob Cowan, editor of Context. |

Wood-block paving, once very common, is now rare in the UK. In London there is a short stretch in Chequer Street, Islington (how much of this is original and how much restoration is unclear) and a few wood-blocked drain covers, and small patches of wood-block paving, occasionally show through where the asphalt has worn away. There may be a few patches in other towns and cities. Ten thousand wooden blocks, dating from 1883, were exposed in 2011 during roadworks in the centre of Dundee. They have been removed and stored.

Wood-block paving seems to have become common in London in the 1840s, to have declined somewhat for a couple of decades after that in favour of granite setts, and to have revived in the 1870s. The noise made by iron-shod horses and carriage wheels on granite could be deafening. An American observer wrote of London in 1878: ‘Some streets have complained that their noisy granite pavement has driven much of their custom into quieter streets, and this consideration is beginning to weigh quite heavily. In the future the contest for public favor is likely to be mainly between wood and asphalt. In spite, however, of the great difference in cost, wood pavement is now taking the lead. It has really no serious drawbacks, except in its cost; it is quiet, and gives good foothold for horses.’ (Ref The Manufacturer and Builder (New York), September 1878, quoted in the online Victorian Dictionary, http://www.victorianlondon.org)

Wood-block paving was particularly valued near hospitals (for its quietness), and where gunpowder or other flammable or explosive materials (such as jute in Dundee) would have been at risk from sparks caused by horses’ hooves striking granite.

Many of London’s streets (including most of the main streets in central London) were still surfaced with wooden blocks in the 1920s. The evidence for this can be seen in Bartholomew’s Road Surface Map of London, published from 1903 at least until the 1920s.

When a street was later repaved with asphalt, the wood blocks were usually either sold or given away. Alan (now Lord) Sugar recalls in his autobiography taking some of his first steps as an entrepreneur by chopping up the redundant blocks and selling them as firewood. Being treated in bitumen they burned well, if somewhat explosively.

Wood-block paving may yet have a future. A development of four houses in London’s Notting Hill by the celebrated architect Peter Salter, completed in 2016, features a courtyard paved in wood blocks. The obsessively detailed scheme is, its developer claims, ‘the product of a decade of learning, thought and inspiration’ which ‘will appeal to the most discerning of buyers and collectors.

This article originally appeared as ‘Iron, glass and wood underfoot’ in IHBC’s Context 152, published in November 2017. It was written by Rob Cowan, editor of Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Archaeology.

- Blockhead.

- Britain's historic paving.

- Coal.

- Conservation.

- Floors of the great medieval churches.

- Floorscape in art and design.

- Florence Cathedral.

- Glass block flooring.

- Glossary of paving terms.

- Gridder.

- Hazard warning surfaces.

- IHBC articles.

- Kerbs.

- Manhole.

- Manhole cover.

- Pavement.

- Road paving.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- The Livery Halls of the City of London.

- Types of floor.

- Types of road and street.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.

Comments