Passive building design

|

'Passive design uses layout, fabric and form to reduce or remove mechanical cooling, heating, ventilation and lighting demand. Examples of passive design include optimising spatial planning and orientation to control solar gains and maximise daylighting, manipulating the building form and fabric to facilitate natural ventilation strategies and making effective use of thermal mass to help reduce peak internal temperatures.' Ref Home Quality Mark One, Technical Manual SD239, England, Scotland & Wales, published by BRE in 2018. http://www.homequalitymark.com/standard |

Designers tune the thermal characteristics of buildings so that they moderate external environmental conditions and maintain internal conditions using the minimum resources of materials and fuel.

Passive design maximises the use of 'natural' sources of heating, cooling and ventilation to create comfortable conditions inside buildings. It harness environmental conditions such as solar radiation, cool night air and air pressure differences to drive the internal environment. Passive measures do not involve mechanical or electrical systems.

This is as opposed to 'active' design which makes use of active building services systems to create comfortable conditions, such as boilers and chillers, mechanical ventilation, electric lighting, and so on. Buildings will generally include both active and passive measures.

Hybrid systems use active systems to assist passive measures, for example; heat recovery ventilation, solar thermal systems, ground source heat pumps, and so on. Very broadly, where it is possible to do so, designers will aim to maximise the potential of passive measures, before introducing hybrid systems or active systems. This can reduce capital costs and should reduce the energy consumed by the building.

However, whilst passive design should create buildings that consume less energy, they do not always produce buildings that might be considered 'sustainable' as sustainability is dependent on a range of criteria, only one of which is energy usage.

Passive design can include:

NB: Passive solar design is an aspect of passive building design that focusses on maximising the use of heat energy from solar radiation.

Passive design can include consideration of:

- Location.

- Landscape.

- Orientation.

- Massing.

- Shading.

- Material selection.

- Thermal mass.

- Insulation.

- Internal layout.

- The positioning of openings to allow the penetration of solar radiation, visible light and for ventilation.

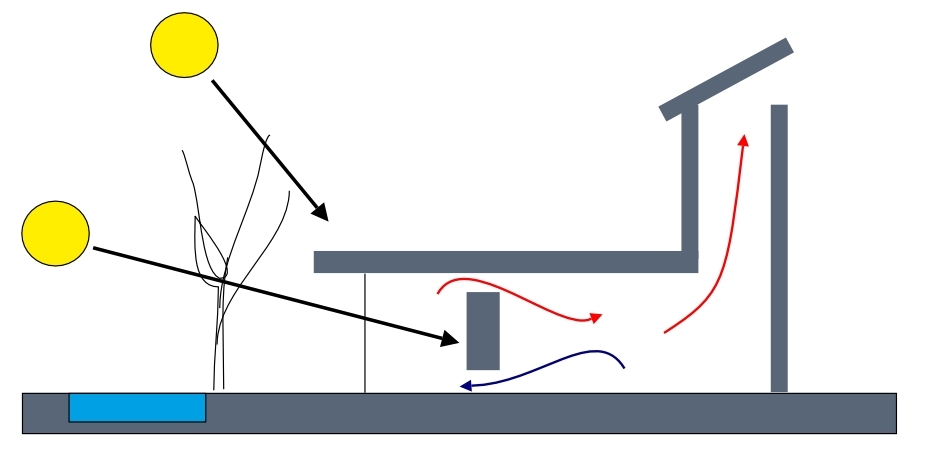

In its simplest form, a shallow building orientated perpendicular to the prevailing wind with openings on both sides, will allow sunlight to penetrate into the middle of the building and will enable cross ventilation. This should reduce the need for artificial lighting and may mean that cooling systems and mechanical ventilation are not necessary. In taller buildings, stack ventilation can be used to draw fresh air through a building, and in deeper buildings atriums or courtyards can be introduced to allow light into the centre of the floor plan.

However, difficulties arise, for example; when buildings have cellular spaces that block the passage of solar radiation and air, or where site constraints create complex massing or mean that windows cannot be opened because of noise or air quality issues. This can lead to the introduction of more complex passive measures, such as trombe walls, solar chimneys (or thermal chimneys), solar stacks, acoustic louvres, thermal labyrinths, and so on.

The situation is complicated further by different climates, changing seasons, and the transition from day to night, so that passive design may have to allow different modes of operation, sometimes rejecting external inputs and expelling the build up of internal conditions, whilst at other times, capturing external inputs and retaining internal conditions.

Typically, these variations can be dealt with through measures such as shading, shutters, overhangs and louvres that allow low-level winter sun to penetrate into the building, but block the higher summer sun. Thermal mass can be used to store peak conditions during the day and then to vent them to the outside at night. Even deciduous trees can be beneficial, their leaves shading buildings from summer sun, but then allowing the solar radiation to penetrate through their bare branches during the winter.

Additional complexities can be introduced by internal heat loads such as people and ICT equipment and by occupancy patterns. In a 9-to-5 office with a moderate amount of installed equipment, it may be possible to use thermal mass to store heat loads during the day and then to vent these and cool the thermal mass when the building is unoccupied at night. This may not be possible with a building such as a hospital that is continuously occupied.

Considering all these issues early in the design process, so that they can be incorporated into the fundamental design of the building, requires close working across the entire design team. The historic model, where the architect designed a building and then a structural engineer made it stand up and then last of all a services engineer made it comfortable, is unlikely to achieve a satisfactory result.

Passive design measures can require occupant involvement, for example to open windows, turn out lights, adjust louvres, and so on. This requires education so that occupants are able to understand the building and to operate it efficiently. Occupant behaviour is often cited as one of the prime causes of the 'performance gap', that is, the difference between the expected and actual energy consumption of completed buildings.

As well as reducing energy consumption, adopting passive design strategies can help building ratings across standards such as PassivHaus, BREEAM, the Code for Sustainable Homes and LEED.

NB: The urban heat island effect, is an effect found in urban environments where the predominance of hard, heat absorbing surfaces results in a higher ambient temperature than in rural environments. It has been found that simply selecting lighter coloured materials that reflect solar radiation rather than absorbing it can significantly reduce urban temperatures and so the need for active systems to provide cooling.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Ancona eco-mansion.

- BREEAM Potential for natural ventilation.

- Brise soleil.

- Building fabric.

- Building services.

- Condensation.

- Cooling systems for buildings.

- Environmental performance.

- Fabric first.

- Ground source heat pumps.

- Heating degree days.

- Heat gain.

- Heat loss.

- Heat transfer.

- Insulation.

- Natural ventilation.

- Night-time purging.

- Passivhaus.

- Passive water efficiency measures.

- Performance gap.

- Solar chimney.

- Solar thermal systems.

- Stack effect.

- Sustainability.

- Thermal comfort

- Thermal mass.

- Thermal storage for cooling.

- Trombe wall.

- Types of building services.

- Urban heat island effect.

- Ventilation.

- Windcatcher.

Featured articles and news

The Association of Consultant Architects recap

A reintroduction and recap of ACA President; Patrick Inglis' Autumn update.

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.

Demonstrating that apprenticeships work for business, people and Scotland’s economy.

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.