Condensation in buildings

Air will generally include moisture in the form of water vapour.

When air cools, it is less able to 'hold' moisture, that is, the saturation water vapour density falls, and so the relative humidity rises. When the relative humidity reaches 100%, the air will be saturated. This is described as the dew point. If the air continues to cool, moisture will begin to condense.

Typically this happens in buildings when warm, moist air comes into contact with cooler surfaces that are at or below the dew point (such as windows) and water condenses on those surfaces.

Moisture can also form as interstitial condensation - occurring within the layers of the building fabric - typically as a result of air diffusing from the warm interior of a building to the cool exterior and reaching its dew point within the construction of the building itself. For more information see: Interstitial condensation.

Condensation affects the performance of buildings, causing problems such as:

- Mould growth, which can be a cause of respiratory allergies.

- Mildew.

- Staining.

- Slip hazards.

- Damage to equipment.

- Corrosion and decay of the building fabric.

- Poor performance of insulation (see Insulation specification for more information).

Condensation can be controlled by:

- Limiting sources of moisture (including reverse condensation, where moisture evaporates from damp materials). For example, replacing flueless gas or oil heaters, providing ventilated spaces for drying clothes, cooking and so on.

- Increasing air temperatures.

- Dehumidification.

- Natural or mechanical ventilation. This is particularly important in cold roofs, where unseen problems can build up, putting occupants in danger of structural collapse. See cold roof for more information.

- Increasing surface temperatures, such as by the inclusion of insulation or by improving glazing.

- Avoiding cold bridges. These are situations where there is a direct connection between the inside and outside through one or more elements that are more thermally conductive than the rest of the building envelope. Thermal bridges are common in older buildings, which may be poorly constructed, poorly insulated and with single skin construction and single glazing. In modern buildings, thermal bridging can occur because of poor design, or poor workmanship. This is common where elements penetrate through the insulated fabric of the building, for example around glazing, or where the structure penetrates the building envelope, such as at balconies. For more information see: Cold bridge.

- The introduction of vapour barriers (vapour control layers) which prevent moisture from diffusing through the building fabric to a point where temperatures might be low enough to reach dew point. For more information see: Vapour barrier.

Some uses of buildings (such as swimming pools) can generate high levels of moisture and so specialist techniques may be necessary to prevent or mitigate the occurrence of condensation.

It is important that any systems introduced to limit condensation are properly installed and maintained to ensure continued optimal operation.

Condensation in buildings is regulated by Part C of the building regulations, and guidance about how to deal with common situations is given in Approved Document C (Site preparation and resistance to contaminates and moisture) and Approved Document F (Ventilation). Further guidance is available in BS 5250 Code of practice for the control of condensation in buildings.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Approved Document F.

- Cold bridge.

- Condensation pipework.

- Damp.

- Damp proofing.

- Dehumidification.

- Designing out unintended consequences when applying solid wall insulation FB 79.

- Dew point.

- Diagnosing the causes of dampness (GR 5 revised).

- Dry-bulb temperature.

- Electrical resistance meters.

- Flashing.

- Humidification.

- Humidity.

- Hygrothermal.

- Interstitial condensation.

- Methodology for moisture investigations in traditional buildings.

- Moisture.

- Moisture content.

- Mould growth.

- Penetrating damp.

- Psychometric chart.

- Rising damp.

- Sling psychrometer.

- Spalling.

- Treating brickwork with sealant or water repellent.

- Water vapour.

- Wet-bulb temperature.

Featured articles and news

Increased vigilance on VAT Domestic Reverse Charge

HMRC bearing down with increasing force on construction consultant says.

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

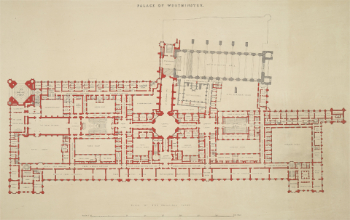

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

Comments

If anyone was uncertain about the causes of condensation in buildings I am sorry to say that this article is more likely to lead to more confusion, with some inaccuracies and poor emphasis. Unfortunately, I haven't the time to rewrite it at present.

I completely disagree. This is a very well researched article with links to a great deal of additional guidance.

If you have a specific issue, say what it is. Simply saying it is confusing but not explaining why is very unhelpful for other readers.

To explain it would require me to rewrite. Perhaps I will do that at some future stage. Thanks for your reply.

I spent a number of years researching thermodynamics so would be very interested to know what you think the problem is. Can you point me to any literature that sets out a different view of the subject?