Max Fordham: Engineering Ideas, Engineering Change

An exhibition at the Building Centre in London until March 24 2023.

A compact exhibition full of the insights and experience of the prolific environmental engineer, Max Fordham, someone who trained as a heating engineer, moved on to services design and then deeper into building physics and sustainability. He redefined the then quite narrow profession of Services engineers into the more holistic profession which is now more commonly referred to as environmental engineering.

The exhibition and web page of the Building Centre venue state:

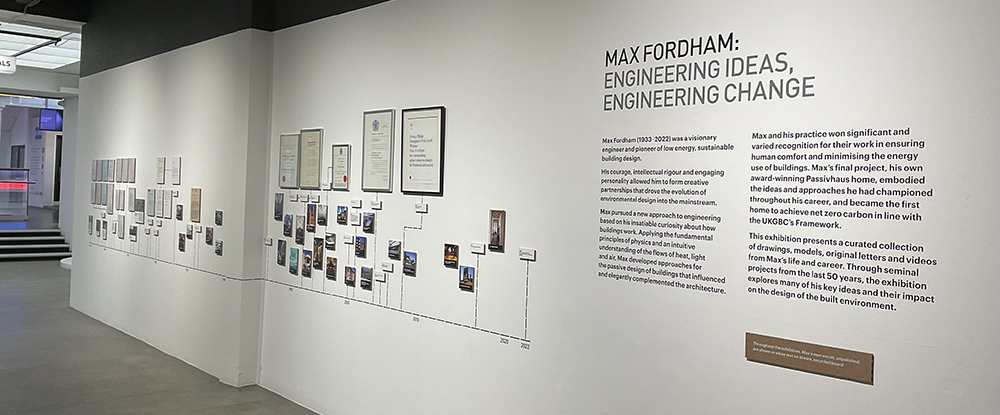

"Max Fordham (1933 – 2022) was a visionary engineer and pioneer of low energy, sustainable building design. His courage, intellectual rigour and engaging personality allowed him to form creative partnerships that drove the evolution of environmental design into the mainstream.

Max pursued a new approach to engineering based on his insatiable curiosity about how buildings work. Applying the fundamental principles of physics and an intuitive understanding of the flows of heat, light and air, Max developed approaches for the passive design of buildings that influenced and elegantly complemented the architecture.

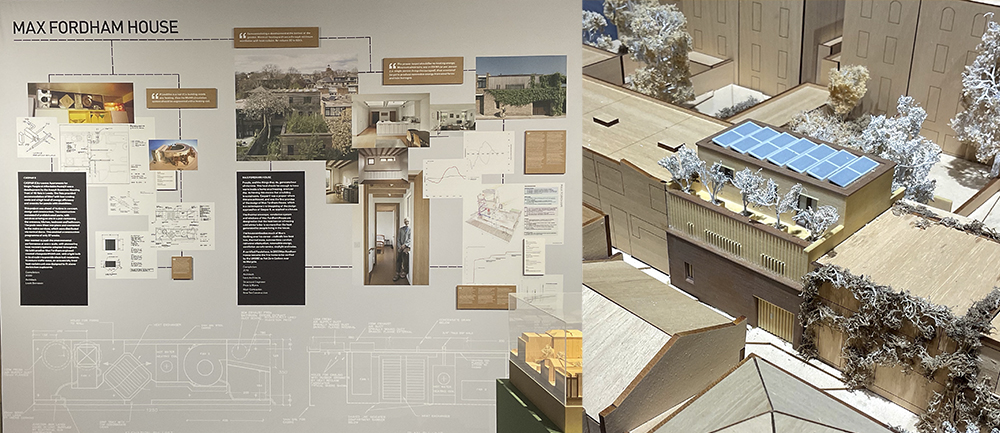

Max and his practice won significant and varied recognition for their work in ensuring human comfort and minimising the energy use of buildings. Max’s final project, his own award-winning Passivhaus home, embodied the ideas and approaches he had championed throughout his career, and became the first home to achieve net zero carbon in line with the UKGBC’s Framework.

This exhibition presents a curated collection of drawings, models, original letters and videos from Max’s life and career. Through seminal projects from the last 50 years, the exhibition explores many of his key ideas and their impact on the design of the built environment."

Contents |

[edit] Exhibition notes

As you enter the room, to the right of the entrance hall of the Building Centre, the original films of Max cycling around London, discussing engineering, co-operative practices and office life draw you in. A long wall to the right displays a timeline of projects and achievements of the man and the practice.

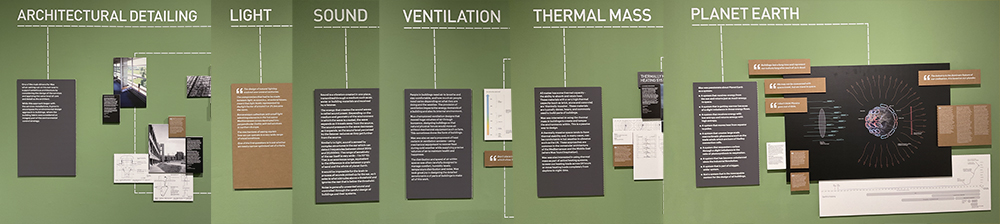

The exhibition is then carefully and beautifully set-out into different themes or core elements contributing to the engineering of human comfort in built environments. The walls display branch diagrams, sketches, photos and notes on themes from detailing to ventilation and light through to planet Earth, picking up how design choices impact performance from the small scale through to the global scale.

A last wall shows sketches, models and photographs of Max's final building, his own house in Camden Mews, on which he worked with Bere Architects and was completed not long before his passing away. Now said to be the first home to achieve net zero, according to the UKGBC framework, it is built to Passivhaus standards but goes further with the introduction of internally insulated shutters to reduce heat loss at night. The display is accompanied by a well-crafted timber model of the house within its setting of Camden Mews.

Finally a joyfully playful table sits in the centre of the room with a number of practice books, knowingly held in place by two CIBSE awards as bookends and accompanied by a box of lego, some Meccano and a small guide. A wonderful touch to describe not only a creativity and playful approach to design, engineering and work but a signal to the next generations of not only engineers but also environmentalists. This is supported by a note board for people to share their own memories, thoughts and ideas, again a nice touch and one that sits well with a practice founded on cooperative ideas..

[edit] Editor notes

In practice I worked on a number of design and research projects with both the London and Cambridge offices of Max Fordham, including innovative low energy buildings across the UK (such as the office of Cullinan Studio) and as far as the UAE. It was only some time after this that I actually met met Max himself, through the coincidence that my brother and his wife moved to London and initially lodged with him and Taddy in Camden, on the basis of also offering home help.

During this time I met both Max and Taddy a few times and was lucky enough to have a couple of long chats with him on the odd evening in the kitchen. I had a barrage of questions ready for him, from the importance of surface temperature differentials to air tightness, wind cowls, natural ventilation, fan powers in MVHR and Passivhaus in warm climates, a little unfair for a man who was, although still very active, by then retired. He was happy enough though to discuss all these issues, and then on to pretty much anything else, in his very gentle, listening, considerate and knowledgeable way.

He had also shown me around some of the many prints he had hanging in his house including many from Neave Brown, who he had worked with on the seminal Alexandria Road project. An RIBA Gold medal winning Architect, who is the only architect to have had all his UK work listed, and who at the age of 73 went on to study fne art and had a close relationship with Max throughout his life. Neave Brown, who died in 2018 was seen by many of us, who had chosen the profession with the goal of building good, affordable, sustainable and accessible housing, possibly romantically, as the ideal architect.

I had known, from the time I worked at the studio of Ted Cullinan that they had at one time shared an office with Max Fordham's practice in Camden, and the two had worked on a number of projects together, including the earth burred RMC low-energy headquarters. As my old boss, Ted too had always been a student hero of mine, for many different reasons, and he too once I had got to know him a little, was an extremely down to earth, practical, funny and generally nice man. His house, one of my favourite buildings, is also on Camden Mews, where Max later built his. Ted died one year after Neave in 2019, I remember it quite specifically because it was the same day as my birthday.

To me at least both Max, Ted and Neave were not only highly respected figures in their professions with a long list of achievements (all receiving the Gold medals from their respective institutes CIBSE and the RIBA). But along with this they stayed in touch with the people element of design, and for the two I met, also on a personal level, and that it seems, to me is what drove them. Service engineering is infamous for complex, unfriendly control systems (which ironically often historically led to higher not lower emissions), whilst Max and his practice of technologists were also proponents of simple design, user friendly controls with a human angle. Ted had been referred to as a humanist architect whose designs focussed on users, the characters he would sketch across nearly all of his proposals. Finally although I never met Neave, his architecture speaks of the same philosophy, stating architects should "relate each house to its neighbour and to its open space, determine the desirable relationships between housing and the attendant functions"

It is no coincidence, whilst Neave worked for London Borough of Camden architecture department, both other practices shared an ideal aligned with the co-operative movement, setting their offices up to function in this way, something that was a rarity at that time, and unfortunately often still is. Whilst Max outlived both Neave and Ted the relationships are perhaps best summarised by Max himself as shared on Max Fordham's practice website.

[edit] Max about Neave

'I was lucky enough to have known Neave Brown for about 60 years. The introduction came through the Pentad Housing Association, where we both worked on the now Grade II-listed Winscombe Street.

Neave was a very clever designer with a strong vision, and a very practical understanding about the way things worked physically. When he was working on the tender drawings for the project, he asked me to work on the building services. He knew exactly what was needed and he brought the plans to me with a list of items that needed to be designed.

The stipulation for ‘clean, modern, electric heating’ became ‘off-peak, electric, controllable, fanned, quiet heating designed to be incorporated into Neave’s special furniture’ under his direction. He included the requirement for ‘plans for the placing of three WC sets, not quite one-above-the-other, to allow for zoning or division into flatlets’. Did this mean I had to prove it was not possible? Not according to Neave. It meant I had to draw a way to make it work.

I learned to enjoy all this with Neave. Other stimulating details arose to suit the architectural programme. Were they all solved? Well, it was great intellectual fun and I appreciated the stimulation he offered. I earned a lot of knowledge and about two and half denarii an hour.

Neave spent a long time on those Pentad houses, but once they were complete he needed to find another job. The new Borough of Camden offered an idealistic framework overseen by then-borough architect Sydney Cook, for what has come to be recognised as ‘Cook’s Camden’. Built during the 60s and 70s, it’s a programme widely regarded as the most important urban housing constructed in the UK in last century.

Neave rose to the challenge, working first on Fleet Road, and then on the greater design challenge at the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate at Alexandra Road. He would proudly tell the story of the Planning Committee rising to a chorus of spontaneous applause when Alexandra Road was presented for approval. While working in Camden he stimulated a similar body of housing work in Camden, Branch Hill, Maiden Lane, Mansfield Road, Gordon House Road and more.

I believe that the economic turmoil of the 1970s, including the introduction of the three day week, led to the decline in the appreciation of architectural value in society. It led to Neave having to change his style of life in many ways. He accepted a professorship at the University of Karlsruhe, moving to a more academic approach to architecture, teaching and further developing his theories. He often commented that, even though his academic ideas and ideals had earned authority and kudos, his detailed design work was less valued.

Having lived in one of the Pentad houses, he downsized to a flat on the Dunboyne Estate in Fleet Road and transferred much of his energy to improving the life of tenants on estates, and attitudes towards property maintenance. He enrolled to study art at Goldsmiths and became an accomplished painter. I would visit with him in the mountains of the Cévennes in France, where we would walk amongst the rocky hills, admiring the cliff scape and engaging in intellectual discussions on social structures, sustainability and the evolution of the human race. The conversations were often quite forceful, even aggressive at times, where no opinion was taboo.

All of Neave’s built work has been acknowledged with heritage listings. He was a thoroughly deserving winner of the RIBA Gold Medal. I thank him for his friendship, and his intellectual rigour. I shall miss him.'

[edit] Max about Ted

‘I first met Ted in 1963, when he and Roz were building their house in Camden Mews. A few years later, when I was moving my recently-formed practice out of the front room of my house into its first proper office space, Ted was having to move out of his current office so I suggested that we share a space. Together we moved into a building in Jamestown Road – Ted and his practice had the 1st floor and we had the 2nd.

Ted and I had similar ideas about design and about running a business. We often used to have a drink after work to talk about buildings and about forming our practices as cooperatives, which we both did in different ways. I hope our practices have many similarities, most notably their democratic structures, their strong focuses on low energy buildings, and their attention to thinking through the problem. We have worked together on numerous projects in our shared histories, including the Grade II*-listed RMC headquarters in Surrey; a naturally ventilated single-storey building with a beautiful garden on the roof, which was Ted’s idea.

I have many fond memories of Ted. Taddy and I enjoyed going to stay at the farm in the countryside that he and Roz bought. We went for long walks and had long talks. I also remember helping Ted dismantle a steel barn that was in his garden. Ted was great fun to work with. He was warm and friendly, very clever about design, and a great collaborator. He retained control of his designs but encouraged discussion about the design process in an open and friendly way. He welcomed everyone’s ideas and liked to find ways to make them work.

Ted was extremely rewarding to work with and will be very sadly missed by me and many others.’

[edit] Peter about Max

Finally a short extract from a piece written by Peter Clegg about Max himself, from the RIBA Journal;

'An important part of his legacy comes from his teaching. He loved being at the centre of intellectual debate, where he could bring scientific understanding to the humanistic study of architecture. He taught me at Cambridge in the late 1960s, and taught with me in Bath for nearly 20 years. He was above all a holistic thinker, whose conceptual approach combined with a pragmatism unconstrained by convention, and a belief that a good idea could always be practically realised. ‘Start with the edge of the universe as a boundary’, he would say, ‘and quickly narrow down to a specific problem.’ It is the breadth of his vision – and the infectious chuckle – for which he will always be remembered.'

--editor

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Building services engineer.

- Environmental engineering.

- Engineer.

- Engineering Council.

- Environmental consultant.

- Environmental impact assessment.

- Environmental modelling.

- Heating, ventilation and air conditioning.

- How to maximise natural light.

- Light shelf.

- Sustainability in building design and construction.

- Sound v noise.

- The sustainability of construction works.

[edit] External references

Featured articles and news

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help the homebuilding sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.

Demonstrating that apprenticeships work for business, people and Scotland’s economy.

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.