Traditional dwellings of Dajun

The small town of Dajun, in Jingning She Autonomous County in China’s Zhejiang province, is known for its many 17th century buildings and as a showcase of She ethnic culture.

|

| The central street of Dajun Town. |

With the development of tourism, Dajun has attracted many Chinese and foreign visitors. The most immediately appealing aspects include the original ecological landscape, the leisure canoe drifting and other folk customs. The traditional buildings are very attractive, especially if one is sitting by the house soaking up the atmosphere of the simple timber frameworks and boulder or soil walls.

With a clear river encircling the town and several small hills at the back, the main traditional residential area is conserved in its entirety. The old cottages are disposed near the hill or along the river. The dominant street system is aligned roughly east-west. About 1,200 years ago the ancestors of the Dajun people first built their homes near the water. Today we still can see many houses scattered along both sides of the Dajun River (a branch of the Oujiang River).

The town consists of hundreds of households. The residential area is divided into two parts by the river. On the west bank of the river, buildings were built near an adjacent bamboo forest. The environment is agreeable, the branches and leaves of bamboo shrouding the outline of the old houses. Some houses abut the hill, the backyards near the hill are not enclosed, and there is usually a kitchen in the backyard. Hill spring water is piped in, allowing people to appreciate the gurgling of natural running water in their home. More buildings are clustered on the east shore of the Dajun River. The residential area is split into two small parts by an east-west central street: these two sections are shaped on plan like two old men, chatting knee to knee. Most houses are built along the river there, next to the flowing water.

Recently, when I was wandering through the old buildings, trying to work out the original appearance of the town, several elderly residents related to me a (perhaps apocryphal) tale about the origins of the settlement. According to this story, early in the 9th century some homeless itinerants came here, attracted by the clear water and the dense bamboo forest, and built their houses in bamboo. Later, in order to adapt to the local climate and environment, a wide range of natural resources were exploited as alternatives for walling and framework building. Timber, mud, clay, brick, stone, straw and other organic materials all played their part in this traditional construction.

Most of the old houses in Dajun date from the 17th century. Generally they feature a courtyard, and have been built oriented north and south to maximise daylight. The typical traditional house plan in Dajun has buildings or pavilions placed along three or four sides of the site, forming a courtyard in the middle. The buildings face the courtyard, which provides outdoor space for family activities, circulation, ventilation, light and drainage. A special feature of the courtyard house is that it is fully enclosed by buildings and walls. There are no windows on the outside walls, and usually the only opening to the outside is through the front gate. According to the fengshui principle, many houses are rectangular with a south-facing gate. The courtyard is normally quite small, in order to create more shade and good ventilation. It is a kind of outdoor living space in good weather, and the loosely defined indoor space is highly integrated with the courtyard. These houses make good use of land, both inner and exterior space being usable.

Courtyard houses were normally built with materials available locally. Wood has always played an important part in the framework and furnishing. The foundations of courtyard houses are generally of stone. In some situations where stone is rare, clay can be compressed into shape or made into bricks for walls. For roofs, depending on the wealth of a family, the material can vary, with pantiles a fairly common solution.

Most of these traditional houses feature a similar kind of wooden framework, named Chuan-Dou. In this system all the purlins rest on the tops of pillars, the load of the roof being carried by the purlins and pillars. Sometimes the masonry walls are also vital support elements. The most popular roof style is the peaked roof (a traditional pattern of Chinese gabled roof). Only a few buildings have a double-eaved roof.

With the development of craftwork and technology, the local house carpenters evolved their own style and decorative detailing. They curved some visible beams into ‘moon beams’, so-called because they were shaped like the crescent moon. Some main doors were especially distinctive in their brick or stone-carved decoration. These traditional architectural details perpetuated the plain style of Chinese folk art, which combines elaborate carving with restrained colouring.

The main body of the house is usually two storeys high. Its plan is oblong, usually with five bays in length and two in width. The central bay on the ground floor is a sitting room, for receiving guests and serving as the central point where all circulation within the house converges. The east room in the main block is the master bedroom or dining room, while the west room contains a guest bedroom. The kitchen is always set near the backyard, behind the guest bedroom. The first floor is about half the area of the ground floor: the main bedroom and living room are situated there. Adjoining these rooms is a very narrow (about one metre wide) corridor, with a wooden staircase at the end of it.

The ordinary house terrace usually features only three steps – very different from the elaborate Xumi terraces of Chinese palaces. It is more concise and plain, without complex decoration and sculpture. However, although the house terrace has only simple moulding work, every stone of the steps is regularly coursed.

The architectural decoration of the traditional houses of Dajun generally stems fairly straightforwardly from the lifestyles of the occupants. There is often a brick carving on the ridge of the roof, as an auspicious symbol: a ‘kylin’ or dragon pattern is common. A pair of round wooden or stone tablets is often hung under the eaves, with the words Double Happiness carved on their surfaces. The brick wall under the eaves is occasionally decorated with a row of mural paintings. The colours are bright and the range of designs wide, based on a variety of Chinese patterning influences. The main lines in these eye-catching paintings are grey with a white background.

The most elaborate architectural ornaments are concave carvings, the main subject-matter of which comprises flowers, deities, animals and so on. Stone carving was too expensive for ordinary inhabitants of the town, but it was greatly favoured by the wealthy: sometimes many carved stones are set around the doors of their mansions.

Most of the traditional buildings in Dajun Town were built in the final Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty (from the 14th to 19th centuries). In general these buildings are durable and plain. In traditional construction, timber, bamboo, clay, brick and stone are used either together or singly. These elements helped stamp local houses with their own regional individuality and contribute to the vast variety of Chinese traditional homes. Recently, however, in an age of rapid modernisation of society, some traditional dwellings have been awkwardly replaced by jarringly individualistic modern concrete-and-glass blocks, which project a strikingly disharmonious note in this area of traditional houses.

It seems plausible to argue, first, that a comprehensive planning scheme should be in place before any new construction begins, and that protection of sites, habitats and landscapes should receive the highest priority. Second, in the design of new buildings, it is not enough simply to collage historic patterns and symbols, as the traditional internal spaces are also worth conserving and studying. Furthermore, although ‘rural urbanisation’ is a dominant trend in the development of modernisation, many local people do not want to change their lifestyles: the low-rise house, small yard and quiet alley remain very popular.

This article originally appeared in Context 141, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in September 2015. It was written by Sun Peifang, a lecturer in the school of civil engineering and architecture at the Zhejiang University of Science and Technology, Hangzhou, China, awarded a scholarship by the China Scholarship Council to pursue study as an academic visitor in the UK.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Chinese renaissance architecture in China and Hong Kong.

- Conservation.

- Heritage value.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Liveable Yangon: for whom?

- MahaNakhon, Bangkok.

- Restoring Singapore shophouses.

- Robot Building, Bangkok.

- The Chinese construction industry.

- The Hong Kong shophouse.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

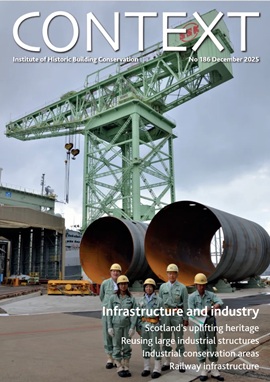

IHBC's 'Context' Issue 186 features Industrial Heritage

IHBC's members' journal reports on the challenges of conserving infrastructure.

Book now for IHBC Annual School 2026

IHBC Annual School is taking place 18-20 June 2026 in Newcastle.

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHeS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am