The decline and revival of food markets

Once the coronavirus crisis has receded, the revival of markets could make a big contribution to building community identity, and making available fresh, healthy, affordable food and diets.

|

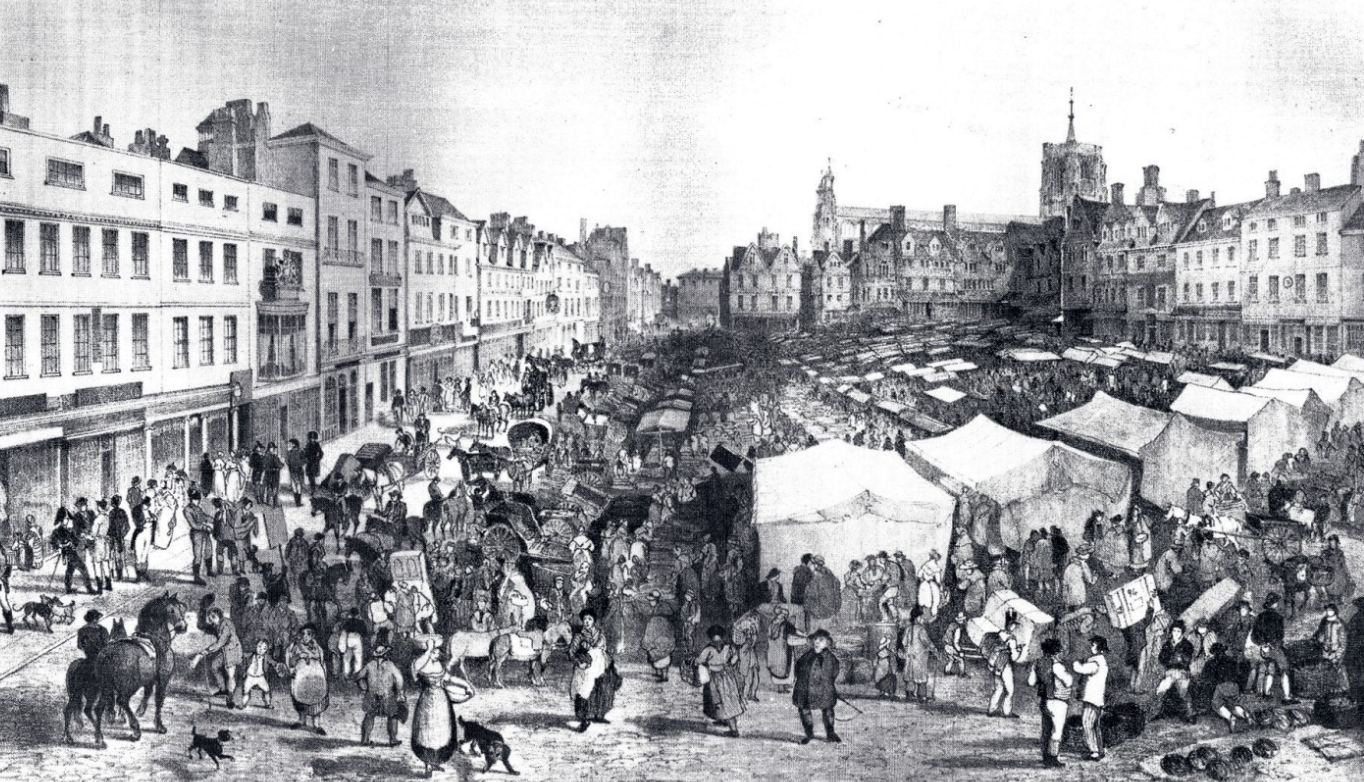

| Norwich Market Place in 1806 by John Sell Cotman. |

In September 2019, almost 800 years after the town of Rochdale was granted a Royal Charter to establish a market, local traders were told that their covered market would be closed the following month as it was no longer viable. This unhappy event is typical of the fate that has affected many historic markets, casualties of the internet shopping revolution, the rise of fast-food outlets and the decline of high streets.

In 2009 a Parliamentary inquiry into traditional markets found that the number in decline was greater than those that were more than holding their own.[1] The committee expressed serious concern, pointing to the contribution markets make to social cohesion, and their role in promoting healthy eating and reducing environmental impact in the retail sector, as well as their obvious economic benefits. Noting that the majority of the 1,000 or more markets in Britain were owned and operated by local authorities, the committee urged those councils struggling to keep their markets alive to consider sharing costs and management responsibilities with the private sector, and to embrace change.

Some historic markets, especially those actively promoted by their local authorities, have kept pace and never lost their appeal. Among these are the open markets at Norwich and Newark, whose loss would be unimaginable. There are also those with spectacular Victorian market halls that are symbols of civic pride.[2] At Leeds Kirkgate, one of the largest markets in Europe, everything from shawarmas to shrimps, chapatis to cockles, and Yorkshire puddings to patisserie can be found beneath the soaring cast-iron-and-glass vaulted market hall. This stupendous structure, designed by John and Joseph Leeming and completed in 1904, is listed Grade II*. The same architects’ slightly earlier market hall at Halifax is equally ornate, with foliated capitals, decorative spandrels and brackets in the form of wyverns. It has recently been repaired and remains the vibrant heart of the town.

Meanwhile Bury Market, which has avoided Rochdale’s fate and those of other proud industrial towns in the north of England, is today one of the liveliest in England. Bustling and colourful, with over 350 stalls crammed into a variety of market buildings and in the open air, Bury celebrates local produce with a huge range of fresh food. Here you will find Chadwick’s original Bury Black Puddings, made to a secret recipe from 1865, and patronised by Prince Charles and the late Ken Dodd. There are fat Eccles cakes, plump Goosnargh poultry and rare breeds of beef from farms in Lancashire, and tempting cafes serving traditional fry-ups. Unlike the sterile supermarket model which has caused the demise of so many markets, at Bury the traders love to chat, while in the liveliest part, the Fish and Meat Hall, they call out their wares in an endless banter of goodwill and entertainment.

Bury is exceptional, but since the Parliamentary inquiry, a number of councils have been looking beyond the traditional market models to attract a wider range of buyers, younger people in particular, and creating opportunities for a different type of market trader. The increasing desire for local produce, both edible and otherwise, is also leading to new ideas. A current trend-setter is Nick Johnson, formerly a director of Urban Splash, who now runs two markets, one in Altrincham, his home town, and another in Manchester. In 2013 he and his partner Jenny Thompson took over from Trafford Council the running of the Altrincham market which, together with a fifth of the shops in the town centre, had been killed off by the nearby Trafford Centre and a Tesco superstore.

Their models were the Boqueria market in Barcelona and Columbia Road in east London, as well as Bury; their selling points are that you cannot get it online, it is handmade and you are dealing directly with the creator. More than 120 traders in the outdoor market, each with something special to offer, include bakers, butchers, chocolatiers, jewellery makers and purveyors of limited-edition jeans. All are from the northwest, and most of the produce is too. The Grade-II listed Market House, which occupies about half the market place, was renovated at a cost of £500,000. Within it now is a range of food and drink units set around a large eating area with shared tables and a sound system for live music and films.

Since it opened, the market’s success has acted as a catalyst for new shops, bars and cafes to open up in the surrounding conservation area. A key reason for its success is flexibility and cost-efficient operating systems: traders are charged a percentage of turnover, thus reducing the risk and encouraging innovation. The only downside has been a 483 per cent increase in business rates slapped on the property by the local authority this year, ostensibly to meet criteria set out by the government’s valuation office agency, and thereby threatening its economic viability.

Johnson’s Manchester project involved renovating the old meat market in the northern quarter of the city, another listed building that had been empty for decades. On a larger scale than the Altrincham Market House, but without any additional space for market stalls, this is strictly a prepared food and drink market, catering for over 10,000 customers a week. The building, known as Mackie Mayor after Ivie Mackie, the Mayor of Manchester when it was first opened in 1858, has been renovated, with a new glazed roof, its rough brick walls left exposed, and a reclaimed timber floor. There are 18 independent kitchens plus beer and wine bars, and customers wander about to see what is cooking and watching the chefs at work, before placing their order, not necessarily from the same counter. Food and drink then arrives at your table. Johnson’s idea is that instead of money leaching out in profits to London or to a multinational, not only the jobs but also the value remains in the region. ‘The money made here stays here,’ he says. ‘It helps with Brexit Britain.’

Some of these ideas underpin other recent market revivals. Stockport’s Produce Hall, a classical stone building of 1852, adjunct to the splendid iron-and-glass Market Hall of 1861, has reopened for independents as part of an ambitious conservation-led regeneration of the Market Place. Other initiatives include the well-received conversion of a section of Wrexham Market into a contemporary art gallery and the conversion of part of Maidstone Market into a town centre distillery and bar. Traditional market traders have often been in conflict with their local authority owners, who are commonly accused of increasing rents and making their businesses unviable.

This has long been the case at Oxford Covered Market, where the traders faced rent hikes of 50 per cent in 2012, and 25 per cent in 2016. But more recently, mutual trust has returned: Oxford City Council is investing £3.1 million in repairs to the fabric of the market building, which dates back to the 1780s, and is preparing a masterplan to increase footfall, improve the trading environment and turn it into a cultural as well as a trading hub. The project has the support of the Market Tenants’ Association, surrounding landlords, Oxford Preservation Society and the Oxford Civic Society.

The rise of the farmers’ market movement, which developed as a reaction to the decline of municipal markets, has connected producers and consumers directly. The markets provide outlets for small local farms that typically sell organic foods and spend less on land, equipment and transport than the large agro-industrial businesses. Most vendors at farmers’ markets, if not the farmers themselves, are self-employed, maybe doing more than one job, and operating within the gig economy. Especially in London, they have spawned the creation of pop-up markets, all based on the groundswell of interest in developing artisan food businesses.[3]

An early example was the takeover of Borough Market in Southwark in the late 1990s by a group of artisan traders who started by holding ‘warehouse sales’. At that time the cast-iron-and-glass market buildings, dating from the 1850s and 60s, were threatened by widening of the Thameslink rail viaduct. Now the market is a charitable trust administered by volunteer trustees who have to live in the area, although the traders come from across the UK and Europe. Another spin-off is the street-food movement: artisan food carts and vans, typically seen at music festivals, have shown there is a big demand for alternatives to hamburger vans. KERB, which started up at Kings Cross and now has several venues across London, has traders with enticing names such as Utter Waffle, Smoke and Bones, Greedy Khao, Baba Dhaba and Mother Clucker. One advantage of street food is that in most cases the trader can ‘move on’ should a particular pitch prove to be unsuccessful.

Yet another change in market operation is the arrival of night markets with a focus on food. In London there are several, including POP Brixton, Dinerama Shoreditch and the all Italian Mercato Metropolitano on Newington Causeway; and in Manchester there is Hatch, a brightly-coloured jumble of shipping containers under the Mancunian Way flyover. They offer the experience of communal eating with innovative street food while enjoying entertainment, theatre and music.

These and other speciality markets cater to a growing population of discerning customers who want better value and more variety, and who enjoy talking about food in the way that Italians do. Thus markets may be returning closer to their origins. Before the 19th century, the market place was not only the retail centre, but also the social and commercial hub of the town, providing a gathering place and helping to build community identity. Perhaps, once the coronavirus crisis has receded, the availability of fresh, healthy, affordable food and diets will take their rightful place once again in the ‘new normal’. The revival of markets could make a big contribution.

References

- [1] Market Failure? Can traditional markets survive? (2009).

- [2] Dobraszczyk, P, (2012) ‘Victorian market halls, ornamental iron and civic intent’, Architectural History, 55.

- [3] Greater London Authority (2017) Understanding London’s Markets http://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/gla_markets_report_web.pdf

This article originally appeared in Context 165, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in August 2020. It was written by Peter de Figueiredo, reviews editor, Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Membership Journal Context - Latest Issue on 'Hadrian's Wall' Published

The issue includes takes on the wall 'end-to-end' including 'the man who saved it'.

Heritage Building Retrofit Toolkit developed by City of London and Purcell

The toolkit is designed to provide clear and actionable guidance for owners, occupiers and caretakers of historic and listed buildings.

70 countries sign Declaration de Chaillot at Buildings & Climate Global Forum

The declaration is a foundational document enabling progress towards a ‘rapid, fair, and effective transition of the buildings sector’

Bookings open for IHBC Annual School 12-15 June 2024

Theme: Place and Building Care - Finance, Policy and People in Conservation Practice

Rare Sliding Canal Bridge in the UK gets a Major Update

A moveable rail bridge over the Stainforth and Keadby Canal in the Midlands in England has been completely overhauled.

'Restoration and Renewal: Developing the strategic case' Published

The House of Commons Library has published the research briefing, outlining the different options for the Palace of Westminster.

Brum’s Broad Street skyscraper plans approved with unusual rule for residents

A report by a council officer says that the development would provide for a mix of accommodation in a ‘high quality, secure environment...

English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023

Initial findings from the English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023 have been published.

Audit Wales research report: Sustainable development?

A new report from Audit Wales examines how Welsh Councils are supporting repurposing and regeneration of vacant properties and brownfield sites.

New Guidance Launched on ‘Understanding Special Historic Interest in Listing’

Historic England (HE) has published this guidance to help people better understand special historic interest, one of the two main criteria used to decide whether a building can be listed or not.