Augustus Welby Pugin

|

| The cathedra of the Archbishop of Birmingham in St Chad’s Cathedral (Photo: James Bradley, Wikimedia Commons). |

Literature and architecture, intertwined, are part of the gothic story. JRR Tolkien was a Brummy, a pupil of the old King Edward’s School, located on New Street, Birmingham. His school was a gothic masterpiece, and many people said it was Birmingham’s best building. Its architect was Charles Barry, but the interiors, and possibly some of the architecture, were by AWN Pugin (Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin). It was the first building project that Augustus Pugin and Charles Barry collaborated on. Charles Barry was very much the senior figure in the partnership. They would go on to build the Palace of Westminster together.

The exhibition about Tolkien at the Bodleian in Oxford in 2018, ‘Tolkien: maker of middle earth’, revealed that as a boy Tolkien was a proficient drawer of architectural detailing. It is easy to imagine the young Tolkien being impressed by the gothic splendour of his school, and perhaps Pugin’s interiors encouraged him to think about medieval England, and to delve further back into history. It is possible that they even helped him to conjure up the places we read about in Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

When Tolkien was married in St Mary Immaculate Church, Warwick, in 1916, he would surely have known that Pugin’s son, Edward, designed it, and he would have been conscious of the Christian symbolism of the gothic architecture, not least because Tolkien was brought up in the Catholic church after the death of his mother when he was 12. That church, and the other gothic buildings of Warwick, probably influenced Tolkien’s writing.

Certainly, if you walk along the remaining section of medieval town wall abutting the garden of the Lord Leycester Hospital, it is easy to picture yourself in Middle Earth, probably in Minas Tirith.

Sadly, the gothic masterpiece of King Edward’s School was demolished in the 1930s and the school relocated to Edgbaston. But some of the interior fittings designed by Pugin were salvaged, including timber panelling and the headmaster’s throne (he really did have a gothic throne), and they went into the new school building. Pugin would go on to design the Sovereign’s throne in the House of Lords.

Birmingham has several surviving Pugin buildings, including St Mary’s Convent in Lozells, the seminary at Oscott, a number of churches, and St Chad’s Cathedral, which contains many Pugindesigned treasures in its crypt.

Pugin was born in 1812, the only child of middle-aged parents, an English mother and a French father, who both doted on him. The family lived in Bloomsbury, London, in a happy household, full of life, and from within the family home Pugin’s father ran a drawing school. Pugin was indoctrinated into gothic design from an early age; as a boy, he made annual trips with his father to study the medieval cathedrals of England and France. At the age of 15 he started working for his father, who was a cabinetmaker as well teaching architectural drawing; and the pair of them, father and son, worked together on furniture for George IV at Windsor Castle.

At 18, Pugin was running his own furniture-making business in London, and he was also designing and making stage scenery for the Covent Garden theatre. At the start of his career, Pugin would travel up to the Midlands, where some of his best clients lived, like Mrs Gough of Perry Hall, and Mrs Amherst of Fieldgate House, Kenilworth, for whom he later built St Augustine’s Church, Kenilworth. Pugin visited Kenilworth Castle with the Amhersts. This is the castle that inspired Sir Walter Scott to write his historic novel ‘Kenilworth’. Scott’s historical novels had a significant effect on British culture in the first half of the 19th century. The young Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were fans, and they were also interested in gothic design. Scott’s novels fuelled Pugin’s interest in medieval gothic design and chivalry.

Pugin’s life became intertwined with the Amhersts of Kenilworth. Later in life he became secretly engaged to Mrs Amherst’s daughter Mary, but the relationship ended when she decided to become a nun. Mrs Amherst’s son, Kerril, was a boy when Pugin first visited the family home. Later, when Kerril went to study for the priesthood at Oscott Seminary, on the edge of Birmingham, Pugin taught him there as the professor of ecclesiastical antiquities. Kerril later became a bishop and remained a good friend to Pugin.

At the age of 19 Pugin designing stage scenery for the Covent Garden theatre, was dating a Covent Garden actress, Anne, three years his senior, who he would take on outings to Christchurch in Dorset. When I visited Christchurch recently I stumbled on an altar table, hidden away in a corner of the priory. The inscription states: This table was made and presented to this church by Augustus Welby Pugin, AD 1831. I wonder if Anne was with him when he presented the table to the church. She might have been waiting secretly outside because Pugin had got Anne pregnant, which would have been scandalous at the time. They eloped and Pugin lied about his age so that they could marry without parental consent. His parents were forgiving and took in the newlyweds, but the next couple of years were tumultuous for Pugin.

After giving birth to a daughter, Pugin’s beloved young wife tragically died. Pugin fulfilled her dying wish that she be buried in the Priory at Christchurch. By the time Pugin was 21, his devoted father and mother had also died, leaving him alone with a baby daughter to look after. After these catastrophes he spent a contemplative time walking around the medieval ruins of Tintern Abbey in the Wye Valley. It was here that he found his true calling to be a gothic designer and he decided to convert to Catholicism.

A few years later, in 1836, at the age of 24, Pugin’s fame was accelerated with the publication of his book ‘Contrasts’. The book contrasts the merits of gothic architecture, or what Pugin refers to as Christian architecture, with classical Greek design, which he dismisses as being pagan. With his combination of architecture and writing Pugin was getting ready to change the face of Britain. A very effective networker and influencer, he used his books to get his ideas about gothic design accepted among the political elite. He would send free copies of his books to the people he wanted to impress and influence.

‘Contrasts’ was a discourse on Pugin’s architectural beliefs, including authenticity in construction, which meant expressing the structure of a building in an honest way. For example, he did not hide the hinges of a door but revealed them, celebrating their function and their appearance. ‘All ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building,’ he wrote. He believed that only gothic or ‘pointed’ architecture could satisfy all of his worthy objectives. He hated classical Greek design, not only because he considered it pagan but because it was based on construction with timber posts and beams, and when the ancients evolved to using stone instead of timber, they continued to build in the same way, rather than applying the true possibilities of stone to create soaring vaults and flying buttresses.

To understand why Pugin became so influential, it is helpful to return to a sunny, spring day in 1837, when he was 25 years old. He travelled up to Birmingham on the brand-new railway, but the project had not been completed on time and it was a coach replacement service that brought him into New Street.

He walked through the splendid Georgian squares of Birmingham with a swagger because his new book ‘Contrasts’ was receiving favourable attention from influential people. Walking along New Street, he saw King Edward’s School, the building he designed in partnership with Charles Barry, under construction. There was not time for him to loiter as he was on his way to a job interview at Oscott, the new Catholic seminary, built on the boundary of Birmingham and the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield. The job was to design the interior of the seminary’s chapel and two new gatehouses leading into the seminary.

The interview at Oscott was lifechanging and it was instrumental in helping him to turn Britain gothic. He won the commission to design the chapel and the gatehouses, and he was invited to stay on at Oscott as their professor of ecclesiastical antiquities, a role created uniquely for him. He was the only lay member of the teaching staff. He stayed at Oscott, on and off, for a year. It was there that he met the Birmingham manufacturer, John Hardman, Lord Shrewsbury and Bishop Walsh, all of whom became his life-long friends, and with whom he would change the face of Britain.

Pugin convinced John Hardman to turn his Birmingham manufactory over from the production of buttons to the production of stained-glass windows and gothic metalwork, which he needed for his churches. They worked together on the ancient craft of glass making, and scaled it up for mass production. They recreated vibrant medieval colours at realistic prices, and Hardman’s Birmingham manufactory went on to produce all windows and the gothic metalwork needed for the Palace of Westminster.

There were other seismic factors simmering away that added to a perfect storm at Oscott seminary in 1837, which would advance Pugin’s gothic cause.

Catholic emancipation was changing the nation. The fact that the Catholic seminary at Oscott had been built at all was remarkable: it followed swiftly on the back of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. This act ended the Anglican supremacy, and changed the political, social, and cultural order of Britain. It meant that Catholic seminaries and churches could be built for the first time since the Reformation, and Catholics could attend university, and be local councillors and Members of Parliament. It meant that Lord Shrewsbury, the highest-ranking earl in the land, who was a Catholic, could take his seat in the House of Lords for the first time.

Oscott College is an imposing building, positioned on a hill overlooking Birmingham, visible for miles around. With its gothic tower it would have been a bold symbol that the Catholic Church was back in business. By 1837, Birmingham was a large manufacturing town, bursting at the seams with migrants from Ireland, most of whom were Catholic. While the town had many smoking chimneys, it had few churches. Lacking the great industrial mills of the north, Birmingham consisted of artisan workshops at the back of the houses of independent craftsmen, who employed apprentices; it was closer to the medieval guilds, which fascinated Pugin.

The growing middle class was increasingly concerned that England’s countryside and its historic towns were being ravaged by the industrial revolution. There was a surge of interest in Walter Scott’s historical novels, which satisfied a romantic longing for an idyllic, more virtuous past. Henry Newman, based at Oscott seminary, claimed that Sir Walter Scott ‘had first turned men’s minds in the direction of the middle ages.’

Pugin wanted to rediscover what had been lost. ‘How little is really known of old English art,’ he wrote. ‘The celebrated cathedral may indeed arrest attention, but few ever penetrate among the many noble churches which lie in unfrequented roads, and where the simplicity of a rural population has proved a far better preservative to the sacred pile than the heavy rates of prosperous and busy towns.’ Pugin was interested in a more virtuous and artistic past. ‘Men must learn that the period hitherto called dark and ignorant far excelled our age in wisdom, that art ceased when it is said to have been revived.’

Pugin collaborated with debonair potter, Herbert Minton, from Stoke-on-Trent, in pursuit of medieval encaustic tiles. After much, sometimes explosive, experimentation, Minton replicated a medieval kiln and perfected the practice of making encaustic tiles, where different coloured clays are fired together. This was then scaled-up to an industrial enterprise to provide Pugin with the thousands of tiles he needed for his churches and the Palace of Westminster.

Before Lord Shrewsbury of Alton Towers inherited his title, he had been John Talbot, living humbly in Hampton-on-the-Hill, near Warwick. As Lord Shrewsbury, he became the fantastically rich benefactor of Oscott seminary in Birmingham and a supporter of Pugin. Following Catholic emancipation, Lord Shrewsbury became a key go-between for the British government and the Vatican, and he promoted Pugin’s work to the Pope.

Before Pugin arrived at Oscott in 1837, he sent a copy of his book, 'Contrasts' to Lord Shrewsbury, who loved it. The earl became convinced that gothic had to be the style for the British Empire. Pugin and Lord Shrewsbury worked together to show how their gothic principles could transform society for the better. They built a new alternative to the dreaded urban workhouse, in the countryside at Alton Towers, based on medieval gothic almshouses. Instead of husbands, wives and children being separated, families remained together in these gothic almshouses and were provided with gardens to grow their own food. Their children were given an education in a little school house.

Pugin immersed himself in the life of the Oscott seminary, including the planning of the first high mass to be held in England since the Reformation. This was held in Oscott’s chapel, with its interiors designed by Pugin, and he was also involved with the design of the mass itself. He put into practice his Covent Garden theatre skills and even designed the vestments worn by the priests. The colour, exuberance and sense of occasion of this high mass brought him to tears.

Following the success of the mass, Bishop Walsh commissioned Pugin to design a new Catholic cathedral for Birmingham, the first cathedral to be built in England since Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s. Pugin also built a fine gothic palace for the bishop. In the 1960s, St Chad’s Cathedral narrowly escaped being demolished to make way for Birmingham’s inner ring road, designed by the city’s chief engineer, Herbert Manzoni. The bishop’s palace was not so lucky: Manzoni destroyed it.

Saint Chad, who was probably born around the year 623 AD and died in 672 AD, reintroduced Christianity to the midlands after the collapse of the Roman empire. Just before Henry VIII’s Reformation, the Catholic priests of Lichfield Cathedral could see the way things were going and they put Chad’s bones in a box, which was sent into hiding in France. This box turned up at Oscott College when Pugin was there. The bones of the saint are now above the altar of St Chad’s Cathedral in a golden casket designed by Pugin. When Pugin completed St Chad’s Cathedral there was a grand procession to consecrate it, orchestrated by Pugin, with a line of priests walking from Oscott to the new cathedral in Birmingham. When Bishop Walsh arrived at the head of the procession carrying the casket containing the saint’s bones, the cathedral’s main doors were flung open, the choir sang, and the bells rang out jubilantly. It was a momentous day for Birmingham, for the Catholic church and for Pugin.

My interest in Pugin is personal. I grew up opposite one of the gatehouses he designed leading into Oscott. Although his gatehouses and the seminary itself still stand and serve their original uses, the council estate I grew up on was demolished when it was less than 40 years old as an architectural and social policy failure. When I was growing up, Pugin’s gatehouse spoke to me of a more excellent world. I later learnt that when he was a teenager he sailed his little boat back and forth from Kent to France, collecting the medieval Christian artefacts from French churches that could be purchased cheaply after the revolution. He donated this collection to Oscott so that the seminarians could learn about medieval Christian arts and crafts. The museum he created is still there.

Through his architecture and his writing, and by applying the principles of craftsmanship that he learnt from studying medieval arts and crafts, Pugin demonstrated that the industrial revolution did not have to be just about mass production, but it could also be about truth, beauty and social justice. This caught the attention of influential people, including William Morris and John Ruskin. Pugin was already promoting pre-renaissance art and architecture when Ruskin was a boy.

Pugin’s house, The Grange, in Ramsgate, which he built for his own family, is undoubtedly an arts and crafts house, built 20 years before the Red House, designed by Philip Webb for William Morris (which is often claimed to be the first arts and crafts house). It was Pugin’s focus on gothic architecture and authentic building techniques and craftsmanship that made him a forerunner of the arts and crafts movement.

Why does Pugin not get the credit for this? Throughout much of the 20th century Victorian architecture was reviled, and Pugin himself was almost forgotten. The Grange fell into disrepair and was rescued from demolition by the Landmark Trust as recently as 1997. But it is the story of the Palace of Westminster that explains Pugin’s rise and fall.

Pugin teamed up with Charles Barry and they won the architectural competition to design the new Palace of Westminster. The nation chose gothic over classical Grecian architecture. Pugin worked day and night for Barry, making over 10,000 drawings for the project, and he was the architect of much of the building. He designed the Elizabeth Tower (housing Big Ben) and all of the palace’s interiors. As a consequence of his overwork he frequently lost his eyesight, and his doctors added to his health problems by prescribing mercury.

Charles Barry took the glory for the Palace of Westminster, and the fees. Pugin was not invited to the opening ceremony or mentioned in the press reports, yet all his team members and contractors were lavished with praise and press coverage. Pugin was almost written out of history partly because he was not an establishment figure and he was unconventional. He was a Catholic convert, he married three times, had eight children, became bankrupt and spent time in a debtor’s prison. He ended up in Bedlam, the public lunatic asylum where up to 2,000 members of the public would queue up every day to torment the insane. His third wife, Jane, was devoted to him, and dramatically rescued him from Bedlam.

Pugin was not just an architect. He designed jewellery, garments, carpets, ceramics and metal work, surrounding himself with craftsmen and builders who brought his designs to life. He ushered in an era of total design with a social conscience. His ideas about authentically expressing the construction of a building are still applied by architects today.

Thanks to Pugin’s work on the Palace of Westminster, gothic became Britain’s national style and it was exported around the world. He only lived to be 40, but he crammed in 100 years of work. He showed that industrial Britain could be about more than mass production: it could also be magnificent.

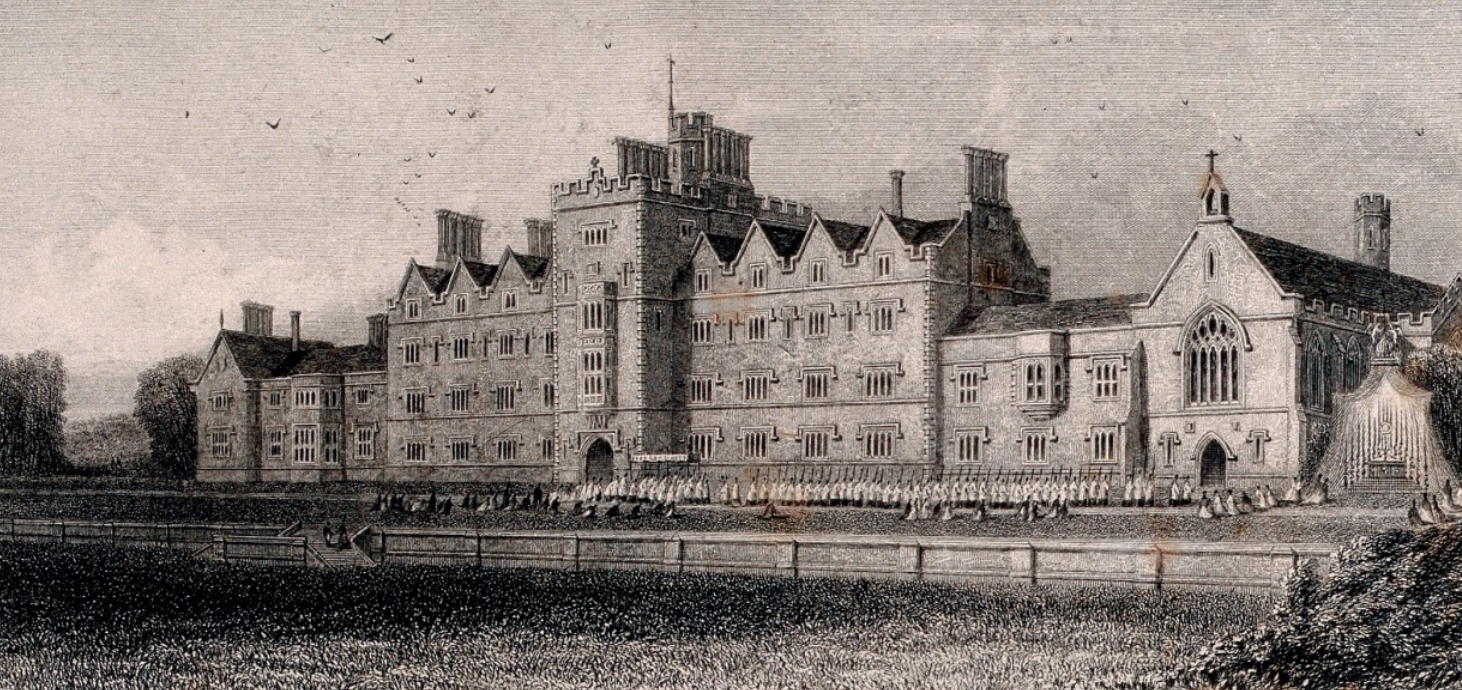

|

| Oscott College, Staffordshire (Etching by W Radclyffe). |

This article was originally published as ‘AWN Pugin: making Britain gothic’ in IHBC's Context 158 (Page 50) in March 2019, and Context 159 (Page 50) in May 2019. It was written by Nick Corbett, associate director (heritage) with WSP | Indigo and the author of Palace of Pugin, published by Transforming Cities.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Architectural styles.

- Arts and craft.

- Buildings of Westminster.

- Conservation.

- Conservation area.

- Encaustic tiles.

- IHBC articles.

- Gothic revival style.

- Classical architecture.

- Making Dystopia.

- Mr Barry's War.

- Oxford Movement.

- Palace of Westminster.

- Restoring Clitheroe Pinnacle.

- Retable.

- Wimpole Gothic Tower conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

Comments

Thank you for your interesing article on Pugin. My son is studying his work in his art lessons partly as his school has a beautiful chapel designed by Pugin. It is only because of this that we I am looking up articles to satisfy my own curiousity and I am very glad I have. I'm not off to look at the Almshouses you have spoken of.

Caroline

Wanted to leave a comment but for some reason I can only do this below the above comment. I enjoyed reading your article very much. Would like to point out one small error though. The church that Tolkein was married in is called "Mary Immaculate Church", not "Mary's Immaculate Church" - though I'm sure that Tolkein found it neat and tidy. :)

Gunnar

We have changed that - thanks for pointing it out. This is the way comments work on wikis - they are really for proposing changes to the article and so other people can edit previous comments.