The development of Irish building conservation

The current planning system in Ireland and the story of its development provide a distinctive context for how historic building conservation is practised today.

|

| Georgian houses in Fitzwilliam Street Lower, Dublin, were demolished in 1965 to construct offices for the state electricity provider. The street is pictured here in 2016. |

The ways in which the historic built environment is understood and valued varies over time and from place to place. However, in contentious political contexts, heritage debates can become more fractious. [1] In Ireland, the dominance and control exerted historically by the country’s nearest island neighbour, and the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922, have both led the independent state to forge a quite different path in conservation terms from the UK. Historically, these aspects of Ireland’s history have often tended to play a central role in debates around historic buildings – in turn impacting on the state’s broad approach and priorities in relation to built heritage – and the historic built environment was for many years not valued to the same degree as in many other western European countries.

There is limited evidence of much concern for the wider historic built environment in Ireland at the start of the 20th century, aside from legislative protection for archaeological heritage, and academic interest in the same. Nevertheless, following the end of the second world war, a growing awareness among the professions of a threat to Ireland’s landscape and towns was reflected in the formation in 1948 of An Taisce, the National Trust for Ireland. While these concerns were initially largely confined to a small elite within Irish society [2], this would slowly change. It was within this context that, in 1957, despite expert recommendations to the contrary, the political leadership of the time approved the demolition of two substantial Georgian houses in Kildare Place, immediately adjacent to the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature). This prompted the foundation of the Irish Georgian Society (IGS) in 1958, the first nationwide independent body set up in the state whose primary aim was the protection of architectural heritage.

Among the landmark cases of the time were the eventual intervention of the state to halt the deterioration of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham in 1955; the demolition of Georgian houses at Fitzwilliam Street Lower, Dublin, in 1965, to construct offices for the state electricity provider; the acquisition of Castletown House by the Hon Desmond Guinness in 1967 and subsequent restoration through the IGS; demolition of Georgian houses by a developer at Hume Street, Dublin, in 1969–70; and the controversy in the late 1970s around development of new offices for Dublin Corporation at Wood Quay (the principal site of Viking settlement in Dublin).

While positive and inclusive representations of pre-independence built heritage strongly prevail today, often emphasising the role of Irish craftspeople and the importance of heritage in tourism and regeneration, historic buildings dating roughly from the 17th century onwards can still at times be perceived by the public in a subtly distinct manner in the shadow of history, characterised by a cultural detachment arising from the endurance of deeply embedded but complex cultural relationships. [3]

In parallel with the controversial cases described above, the planning system of the Republic of Ireland emerged, through which architectural heritage protection is implemented today. The Irish planning system has broad similarities with that of the UK – most notably, the system of local government created in 1898 is similar to UK systems, and the foundational Irish legislation, the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act, 1963, is substantially based upon the UK’s Town and Country Planning Act 1947. However, the Irish Free State (until 1937, thereafter Ireland) was disproportionately dependent upon agriculture, and protectionist economic policies pursued after independence hindered industrial development, resulting in a comparatively lower level of threat to the historic built environment.

By the late 1950s, economic stagnation led government to shift towards a more outward-looking free-trade approach and an emphasis on stimulating and enabling development that still characterises Irish planning today. Moreover, private property rights are protected under Bunreachtna hÉireann (Constitution of Ireland), which has resulted in a tendency sometimes to prioritise these rights at the expense of wider regulatory goals. There has also been a tendency for Irish representative democracy to be characterised by clientelism and individualism. [4] In this context, conservation was less central to the 1963 Act than in UK legislation, with only discretionary provision made for local planning authorities to protect architectural heritage. It was only through Ireland’s ratification of the Granada Convention in 1997 that a comprehensive system of architectural heritage protection was finally put in place.

More specifically, despite some limited earlier attempts at architectural inventories, a National Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) was established on a statutory basis in 1999. Also, Part IV of the Planning and Development Act, 2000 (hereinafter referred to as the 2000 Act) introduced mandatory protection of structures of heritage significance, by requiring each local authority to include a record of protected structures (RPS) under its development plan; architectural conservation areas (ACAs); conservation grants for protected structures; and powers of enforcement, among other related provisions. The fundamental features of these legislative provisions have been set out recently by others, [5] and are therefore not repeated again here; however, a number of related points are discussed.

First, heritage significance is determined on the basis of eight categories of ‘special interest’: architectural; historical; archaeological; artistic; cultural; scientific; social; and technical. The scope for protection is therefore expansive, broader than in the UK, and broader even than the Granada Convention. Despite this, these categories arguably have considerable additional potential to contribute to more comprehensive, inclusive and representative identification and assessment of built heritage significance, and more effective protection and management, through greater use of innovative participatory approaches.

Second, the concept of ‘character’ is central to legislation and guidelines, and while guidelines indicate material attributes that may contribute to character, the relevance of intangible and associative factors (such as symbolism, memory and identity) is only fleetingly mentioned. These factors and their implications for identification and assessment of heritage significance deserve much greater attention, [6] particularly given that more integrated and inclusive approaches are increasingly seen as essential to both sustainable urban development and effective built heritage conservation. [7]

Third, although ratings of significance are assigned in the NIAH, this is not the case in RPSs. In part to address this, an owner or occupier of a protected structure can seek a declaration determining the full range of works that would not materially affect the character of the structure, and which would therefore not require planning permission. In theory, this system offers the potential to respond sensitively in each case, but it places a heavy burden on already stretched local authority resources. Moreover, the high level of default protection arguably leads to uncertainty around what aspects of a structure contribute to its character, and may even contribute to a public perception that protection is an unfair burden. [8]

Fourth, ACAs have to date had varying levels of success, for example suffering from inconsistent implementation and a perception that the designation can stifle change. [9] However, a number of amendments to the primary legislation and guidance have been proposed, to create greater consistency, and to make it easier for local authorities to deploy the designation more frequently and effectively.

A review of the operation of Part IV of the 2000 Act was published in 2016, indicating that the existing legislation on the whole works well, and proposing numerous refinements to legislation and guidance rather than fundamental changes. While many proposed recommendations have yet to emerge, some are already reflected in an increased emphasis in recent years on the instrumental role of heritage. This is evident, for example, in policies, grants and incentives that emphasise the role of the private sector in meeting employment and regeneration goals – echoing wider trends in planning over the last two decades. [10]

However, there are risks should conservation become too reliant on the role of the private sector, coupled with comparatively low levels of direct state grant aid. This approach has the potential to shift the policy focus in favour of external capital (investors, tourists) at the expense of cultural priorities and local interests. This in turn has the potential in certain cases to exacerbate dereliction and decay, and even contribute to the erosion of a local sense of place and identity. Nevertheless, given that the national system of conservation-planning had been in existence for less than 10 years by the time of the 2008 financial crisis (which hit Ireland disproportionately hard), the system is arguably still in its infancy and relatively untested.

The current system furthermore represents a very significant improvement in built heritage protection. Alongside its history, this sets Irish conservation-planning apart and provides a distinctive context for the practice of historic building conservation in Ireland today.

References

- [1] Graham, B J and Howard, P (eds) (2008) The Ashgate research companion to heritage and identity, Aldershot, Ashgate

- [2] Hanna, E (2013) Modern Dublin: urban change and the Irish past, 1957–1973, Oxford, Oxford University Press

- [3] Parkinson, A, Scott, M and Redmond, D (2017) ‘Revalorizing colonial era architecture and townscape legacies: memory, identity and place-making in Irish towns’, Journal of Urban Design, 22(4), pp502–519

- [4] Parkinson, A, Scott, M and Redmond, D (2018) ‘Contesting conservation-planning: insights from Ireland since independence’, Planning Perspectives (published online ahead of print, 20 August 2018) available at https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1509016 (accessed 1"December 2019) )

- [5] O’Rourke, M (2018) ‘Heritage Protection in Ireland’, IHBC Yearbook 2018, pp87–88

- [6] Jones, S (2017) ‘Wrestling with the social value of heritage: Problems, dilemmas and opportunities’, Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage, 4(1), pp21–37

- [7] Veldpaus, L, Pereira Roders, A R and Colenbrander, B J (2013)‘Urban heritage: putting the past into the future’, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 4(1), pp3–18

- [8] AHRRGA (Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs) (2016) Part iv Planning and Development Act 2000 (as amended), Review of Operation Expert Advisory Committee Report, Volume 1. Dublin: Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs

- [9] Matthews, T and Grant-Smith, D (2017) ‘Managing ensemble scale heritage conservation in the Shandon architectural conservation area in Cork, Ireland’, Cities, 62, pp152–158

- [10] Scott, M, Parkinson, A, Redmond, D and Waldron, R (2018) ‘Placing Heritage in Entrepreneurial Urbanism: Planning, Conservation and Crisis in Ireland’, Planning Practice & Research (published online ahead of print, 15 February 2018), available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1430292 (Accessed 1"December 2019)

This article originally appeared in IHBC's Context 163 (Page 12), published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in March 2020. It was written by Arthur Parkinson, assistant professor in planning and urban design at the school of architecture, planning and environmental policy, University College Dublin.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Conservation.

- Conservation and the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland.

- General Post Office, Dublin.

- Heritage protection in Ireland.

- Heritage.

- Housing availability, recruitment and retention in Dublin.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Ireland's climate change sectoral adaptation plan.

- Learning from the failures of the 1960’s and regenerating mass housing in an attempt to tackle social and economic deprivation in relation to Ballymun, Dublin.

- The conservation challenge facing Ireland's industrial heritage.

- The role of architectural conservation officers in the Republic of Ireland, 2000-2020.

IHBC NewsBlog

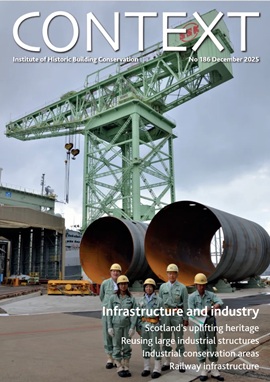

IHBC's 'Context' Issue 186 features Industrial Heritage

IHBC's members' journal reports on the challenges of conserving infrastructure.

Book now for IHBC Annual School 2026

IHBC Annual School is taking place 18-20 June 2026 in Newcastle.

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHeS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am