Skara Brae and Scotland's dynamic coast

|

| A neolithic house at Skara Brae in its coastal setting, showing the survival of drystone-built furniture (Photo: Laurence Winram). |

Our climate is changing at an extraordinary rate. The last century has been characterised by increasing temperatures, altering patterns of precipitation and increased frequency of unpredictable and extreme weather events. In Scotland, since the early 1960s, annual precipitation levels have increased by over 20 per cent, average annual temperatures are 1° celsius warmer, the growing season has been extended by over a month and sea level rise has accelerated to over 3mm a year. The broad future trend is anticipated to be towards warmer, wetter winters and hotter, drier summers, with sea levels continuing to rise. This has implications for the historic environment, with changing climatic conditions having potential to alter and accelerate decay processes of historic monuments and archaeological sites.

Sea levels around the UK have risen by 15–20cm since 1900 and the latest sea level projections (UKCP18) are around 30 per cent higher than previous projections (UKCP09). The extent of sea level rise depends on where one is in the UK, and our future success in adhering to international agreements on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. However, the Met Office anticipates that sea level will continue to rise beyond 2100, even if globally we achieve a substantial reduction in emissions. In Orkney, sea level within the Bay of Skaill is expected to be up to one metre higher within our children’s lifetimes if emissions continue as they are at present. Inevitably rising sea levels will increase the rate and extent of coastal erosion, with the extent also influenced by wave height and coastal sediment supply. This will further exacerbate coastal flooding, leading to loss of, and damage to, many heritage assets. While in the past, some of Scotland’s coasts have been protected by the continuing process of isostatic uplift following the last ice age, evidence now indicates that sea level rise is outstripping this.

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) and its predecessor organisations have been managing the impacts of coastal erosion for decades. Sites we look after have had sea defences in place for many years and range from prehistoric sites like Skara Brae to early modern fortifications such as Fort George. In many cases, these defences have been very effective but, of course, require ongoing monitoring and maintenance and will come under increasing pressures as climate change intensifies. At Skara Brae, we are working in partnership with many other bodies to understand the coastal processes at work in order to actively inform our ongoing management of the site.

The prehistory and history of Skara Brae is inextricably linked with its landscape setting, its exposure to natural hazards, its archaeological investigation and excavation and efforts to preserve it for future generations to enjoy. Skara Brae comprises a network of early prehistoric houses, with drystone furniture still in situ, including beds, fireplaces and dressers. The level of preservation for a domestic settlement of this age is exceptional within northern Europe. The site forms a key element within the Heart of Neolithic Orkney world heritage site (WHS), inscribed in 1999, and is a scheduled monument and a property in the care of Scottish ministers, with management delegated to HES.

Skara Brae is located in the Bay of Skaill, on the west coast of the Orkney Mainland. It is the remains of a neolithic village occupied from c3,100 to 2,500BC, which was around 1km inland when occupied, situated next to a freshwater loch that was separated from the sea by a dune system to the west. This was breached by the sea c1,000BC, leading to the creation of the horseshoe-shaped bay seen today. The site remained hidden under windblown sand until it was partly uncovered during a storm in 1850, which stripped vegetation and sand from a dune known locally as Skerrabra. Antiquarian investigations and clearance took place in 1850-67 and 1913.

The site came into state guardianship in 1922, with a sea wall then being constructed in 1925-26 following a further storm in 1924. Further work on the site in the 1920s included excavations directed by V G Childe. The monument was originally scheduled in 1928, the year Childe began his excavations. Further smaller scale excavations, directed by D V Clarke of National Museums of Scotland in 1972-73 successfully obtained the first radiocarbon dates from the site, confirming it as neolithic. There are two main phases of construction evident in the excavated remains. The earliest phase consisted of freestanding buildings with the later phase consisting of larger houses of a similar plan, largely built into midden material and connected by roofed passageways. The sea wall has been augmented at intervals since the 1920s, with repair and maintenance ongoing, and a rolling programme of sea wall toe reinforcement extension works to enhance footing constructed in the 1980s.

In January 2018 HES published the first phase of our climate change risk assessment project, detailing the risk to our properties in care from natural hazards such as flooding and coastal erosion. The project was carried out in partnership with the British Geological Survey and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency. Of the sites analysed, we found 31 at high or very high risk of coastal flooding, and 24 sites at high or very high risk of coastal erosion. With many of HES’ sites situated on the coast, these results were expected but it came as a surprise to some that Skara Brae was not identified as being at high risk. This is a reflection of the nature of the coastal erosion dataset used, and the fact that the site has been protected by a sea wall for nearly 100 years. Since this initial analysis, further opportunities have arisen for us to explore the processes ongoing at this site and new climate projection data is now available.

A major research project commissioned by Scottish Government and funded by Scotland’s Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW), entitled Dynamic Coast: Scotland’s National Coastal Change Assessment, began in response to risks identified in the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (UK-CCRA). Dynamic Coast has mapped coastal change in Scotland over the last hundred years or so, in the process developing a deep understanding of past change and current vulnerability. The project aims to aid relevant authorities in identifying parts of the coast that may require additional support. The identification of susceptible assets will help inform the development of plans robustly based on a strategic, objective and publicly available evidence base (DynamicCoast.com). HES has been heavily involved in this project from its inception and sits on the steering group ensuring that the historic environment is fully incorporated within the project. This has enabled us to deepen our understanding of coastal change at many sites, including those in our care.

|

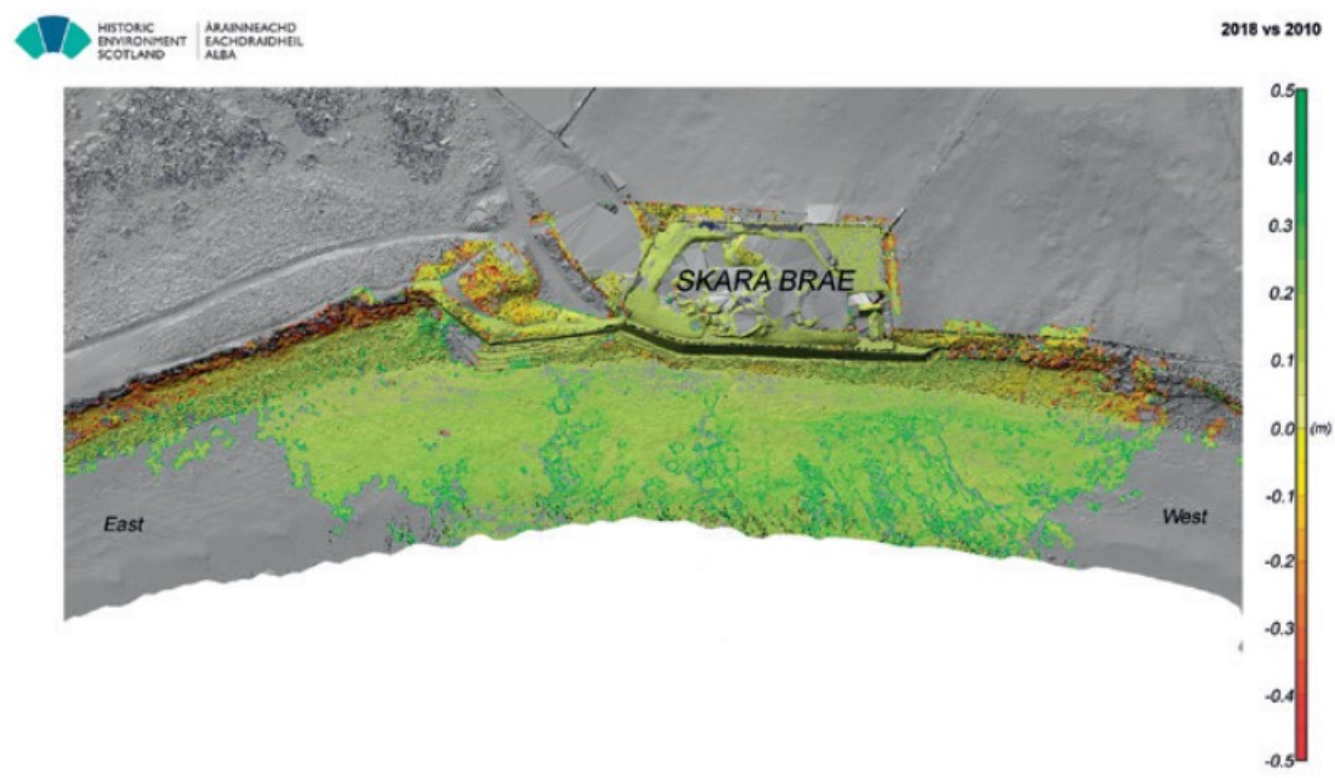

| A deviation map created from laser scans of Skara Brae, its sea wall and environs, comparing data from 2010 and 2018 to identify coastal change and current vulnerabilities (Photo: Historic Environment Scotland). |

In the Bay of Skaill, examination of data from Ordnance Survey mapping indicates that the average height of spring tides (or ‘mean high water springs’, MHWS) remained stable for much of the 20th century in the vicinity of the Skara Brae sea wall but this may mask long term trends and the impact of wave erosion above and below the high tide level. Aerial imagery clearly demonstrates that without this defence, part of the site may have already been lost to coastal erosion and it is likely that the sea wall is contributing to increased rates of erosion on the unprotected soft-coast on either end and in front of the protected area.

HES began a digital monitoring programme for the site several years ago. Every two years, we now undertake a terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) survey of Skara Brae and its surrounding beach to capture mm-scale accurate digital scans of the site and surrounding coastline. Comparing these TLS surveys with other data, it appears that MHWS has not eroded further inland than its 1900 position. However, the TLS survey provides much more detail, showing modest build-up of sediments in the active central area of the bay to the north of the sea wall. The accumulation of sediment is thought to be sourced from erosion of both the crest of the beach and from the lower foreshore. While the stability of the upper beach is good news, the losses elsewhere are a concern, and highlight the value of multi-year detailed three-dimensional analyses.

While coastal erosion remains a threat to the long term survival of the site, the results of Dynamic Coast along with our own monitoring regimes indicate that the existing sea defence continues to fulfil its function of protecting the site. Regular monitoring and enhancement will continue, and the Bay of Skaill is a case study in the ongoing, second phase of Dynamic Coast, which incorporates further data from LiDAR (a 3D aerial survey method which uses pulsed laser light). HES is working closely with the Dynamic Coast team to combine available data sets at a variety of scales to enhance our understanding of the processes at work and the site’s vulnerability. This is informing our plans for management of the site and any future interventions will be underpinned by this robust analysis, taking full advantage of the potential of technological developments.

This article originally appeared as Climate change: Skara Brae and Scotland’s dynamic coast in IHBC’s Yearbook 2019, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in 2019. It was written by Mairi H Davies, climate change manager at Historic Environment Scotland. Previously an inspector of ancient monuments, she is one of the principal authors of HES’ 2018 volume on climate change risk assessment for the HES Estate.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Caithness Broch Project.

- Conservation in the Highlands and Islands.

- Conservation.

- Conversion of Blairtum House, Scotland.

- Development of sustainable rural housing in the Scottish Highlands and Islands.

- Engaging communities in our Highlands and Islands.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Lord Leverhulme on Lewis and Harris.

- Orkney gables.

- Re-thatching a Hebridean blackhouse.

- The challenges and opportunities of conservation in the Highlands and Islands.

- United Free Church of Scotland: Design for Manses in the Highland Districts.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?