The valleys - past, present, future

|

| Ebbw Vale, perched on steep slopes at the head of the Ebbw valley (Photo: © Crown copyright 2020, Cadw). |

The development of ironworking and coal mining on an industrial scale radically changed the economy, society and environment of Wales in the 19th century. Across the South Wales Valleys in particular, the landscape itself was reshaped by the demands of industry, by the extraction, movement and processing of raw materials, and by the development of settlements to house a rapidly growing work-force. In the Rhondda, for example, the population grew from under 1,000 in 1851 to 153,000 by 1911. The most dramatic changes took place in the hitherto sparsely populated uplands, where entirely new urban settlements took root on land that had once supported only upland farms and sheep-walks. But even in areas where there was already an urban tradition, the demands of industry prompted development on a scale and of a type that had hitherto been unknown.

Many of the new settlements occupied topographically challenging locations in steep-sided valleys where iron ore and especially coal were at their most accessible. Such locations sometimes forced an unusual urban structure, in which a string of smaller settlements — each linked to a particular workplace — gradually fused together, though still retaining their individual identity. The landscape also called for considerable ingenuity in building on steep ground, in particular the distinctive stepped or acutely angled terraces that are so characteristic of the Valleys. The very rapid growth of these settlements, and their particular social complexion contributed other distinctive attributes, notably a striking uniformity in the type of building (overwhelmingly terraced houses) and in building style and materials, giving these settlements a remarkable coherence.

A town is much more than a collection of houses, no matter how extensive. A complex urban ecology developed in many of the Valleys’ towns. Civic and cultural institutions were established, of which the most celebrated are probably the miners’ institutes and the chapels. An urban economy was supported by trade and commerce, bringing a range of other building types including pubs, shops and markets.

Towards the heads of the valleys communities were less topographically constrained. Blaenavon, for example, is spaciously laid out with residential streets flanking a high street, and Tredegar is essentially a planned town. Other urban settlements developed with a more conventional structure. Some of the older settlements such as Aberdare and Merthyr Tydfil were essentially remade in the 19th century by the sheer intensity of industrial development. Merthyr Tydfil became the largest town in Wales for a while and was perhaps the place that gave best expression to an urban and industrial way of life. Merthyr’s development reflects the importance of the iron industry in the first wave of industrialisation and urbanisation in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but much of its architectural sophistication reflects the wealth later generated by mining.

All these industrial towns were dependent on a limited economic base. By the interwar period, the grim realities of economic collapse had asserted themselves, leaving many of them struggling. In Merthyr, unemployment was at 62 per cent by 1932 and the population was falling. In 1939 a parliamentary report even recommended that the town be completely abandoned, and the population moved either to the Usk valley or to the coast. A more interventionist government after the Second World War helped create a climate of renewal here and in other towns across the region, manifesting in a range of public projects, and in resources for slum clearance and redevelopment. Any confidence restored by this investment was eroded in the later 20th century by the dismantling of the coal industry, which posed a new threat to Valleys communities.

Since then, a series of regeneration initiatives and funding programmes have channelled resources into these communities. In recent years, these have included specific regional programmes such as the Heads of the Valleys programme, as well as more general regeneration frameworks, such as Vibrant and Viable Places, and Building for the Future. There is now also a Valleys Taskforce seeking to deliver change for the South Wales Valleys around the three themes of jobs and skills, public services, and the local community.

Although heritage has not been the main driver in any of these initiatives, all of them have brought some benefits to the historic environment, including investment in conservation and reuse schemes for individual historic buildings. By tackling some of the worst effects of serious economic decline, regeneration programmes have also helped to create a climate in which heritage can be recognised and valued. The Valleys Regional Park, which was launched by the Taskforce in 2018, aims to ‘unlock and maximise the potential of the natural and associated cultural heritage of the Valleys to generate social, economic, and environmental benefits’.

But how is ‘cultural heritage’ to be defined? These communities have a strong sense of identity, and a highly distinctive landscape character. There is also their legacy of industrial heritage sites, some of which form a regional route in the European Routes of Industrial Heritage. But what of the wider historic environment that contributes so much to the distinctiveness of the landscape?

In terms of designated assets, many of the Valleys’ towns have relatively small numbers of listed buildings and conservation areas: in the whole of Rhondda Cynon Taf, for example, there are only two conservation areas (both in Tredegar), and 53 listed buildings. Even Merthyr Tydfil only has 234 listed buildings and eight conservation areas; although a heritage strategy produced in 2009 recommended 17 new conservation areas, only five additional ones were designated.

There have been some successful projects targeting individual historic buildings. Notable examples include the former town hall in Merthyr Tydfil, reborn as the Red House centre for the arts and creative industries. The dereliction of the town hall had been a sad commentary on the depth of economic decline in the town; it is now a focal point of urban renewal. The former general office building of the Ebbw Vale Steel, Iron and Coal Company, known as The Works, has been refurbished as an archives and library, meeting and conference facility.

Alongside the flagship projects like these, there has also been some area-based heritage investment. Townscape Heritage initiatives in Pontmorlais, Merthyr Tydfil (2011), and in Aberdare (began in 2009), for example, have helped to transform the high streets in both towns.

But the balance between site-based investment and area-based investment is a difficult one to strike. There is a risk that large-scale building projects may divert attention and resources from the fabric and character of the wider urban landscape. Major buildings such as Cyfarthfa Castle urgently need investment, but there is also vulnerable heritage value in the housing stock surrounding it. An ambitious new plan for Cyfarthfa focuses on the castle, park and furnaces, and the area immediately surrounding them. It aims to set a standard for development throughout the town; the challenge will be to identify a vehicle that puts this aim into practice. Investment in specific building projects should be a catalyst for wider regeneration, and it is important that opportunities for that to happen are fully realised.

Although there are many iconic buildings in the Valleys’ towns, their built heritage also rests in the character of the general building stock. Although there have been some attempts to capture the heritage value of the ordinary, there has been no consistent framework for doing so, and initiatives have come and gone. For example, My Valleys House was a web-based resource aimed at providing home owners with information about how to care for and improve Valleys’ housing, and provide a historical and architectural context for it. It emphasised the importance of the ordinary and promoted the reversal of unsympathetic renovation. There is no obvious trace of it now.

This illustrates the truism that investment in individual heritage projects does not automatically lead to the kind of step change that puts the historic environment and its conservation at the heart of regeneration for the long term. Progress has been made, but it has been sporadic: there are still many historic buildings at risk across the region. The traditional character of the wider housing stock is being eroded by incremental change, and modern developments can undermine local identity.

One notable success story is Blaenavon, where the protection of heritage has formed a consistent theme since the 1970s. At that time, the town faced a loss of purpose and of population in the wake of a series of pit closures, but the historic ironworks were taken into state care in 1974 and plans to convert Big Pit into a museum predated the closure of the mine in 1980. Just three years later Big Pit opened as a museum and in 1999 responsibility for the site was assumed by the National Museums and Galleries of Wales (as NMW was then called). The town centre was designated as a conservation area in 1984.

All of this laid the foundations for World Heritage status, and after a period of sustained effort, the Blaenavon Industrial landscape was inscribed in 2000. This encouraged a massive programme of investment. New uses were found for derelict buildings, and property improvement grants were used to preserve or restore historic features such as sash windows, chimney stacks or traditional render. This investment continues in a Townscape Heritage Programme which builds on previous regeneration activity and is seeking to continue the momentum of earlier conservation-based investment. The programme is a partnership led by Torfaen County Borough Council and the lead funder is the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Being part of a world heritage site, Blaenavon is clearly exceptional for the extent and completeness of the industrial landscape, and its capacity to illustrate in material form the social and economic structure of industry in the 19th century. But many of its characteristics are shared with other towns in the South Wales Valleys, some of which arguably have a richer urban heritage, albeit perhaps a more fragmented one.

Blaenavon has worked consistently to protect and promote its heritage, which it has put at the heart of its planning. It had begun to do this before inscription as a world heritage site, and although inscription has clearly helped it to attract funding support and visitors, there are lessons in its story that might resonate elsewhere.

The argument for protection and conservation of the historic environment is never won, and must be made again and again. Turning the promotion and celebration of heritage in general into the protection of specific qualities of place requires commitment, investment, and painstaking attention. It also needs leadership, partnership and vision as well as consistency and focus over the long term. But it is worth it. With care, the sense of place forged in the South Wales Valleys in their extraordinary glory days can also be the basis of their identity, culture and appeal for the future.

This article originally appeared in the IHBC Yearbook 2020, published by Cathedral Communications Ltd in August 2020. It was written by Judith Alfrey, Cadw’s Head of Regeneration and Conservation. She was the co-author of two books promoting the preservation of industrial landscapes, and has written various articles detailing the conservation work of her organisation.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Architecture of the industrial revolution.

- Cautions or formal warnings in relation to potential listed building offences in England and Wales.

- Civil Engineering during the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

- Conservation.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Industrial Heritage Protection and Redevelopment.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Recording old industrial sites.

- Small vernacular agricultural buildings in Wales.

- Use of injunctions in heritage cases in England and Wales.

IHBC NewsBlog

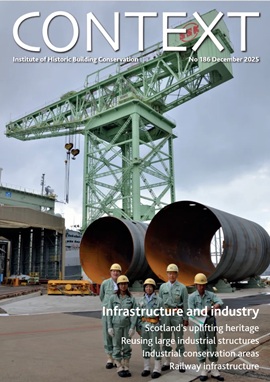

IHBC's 'Context' Issue 186 features Industrial Heritage

IHBC's members' journal reports on the challenges of conserving infrastructure.

Book now for IHBC Annual School 2026

IHBC Annual School is taking place 18-20 June 2026 in Newcastle.

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHeS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am