Strategic urban design and the conservation team

Where can the design skills be found to meet the desperate need to feed an understanding of urbanism into the development plan process? The answer may be in the conservation team.

|

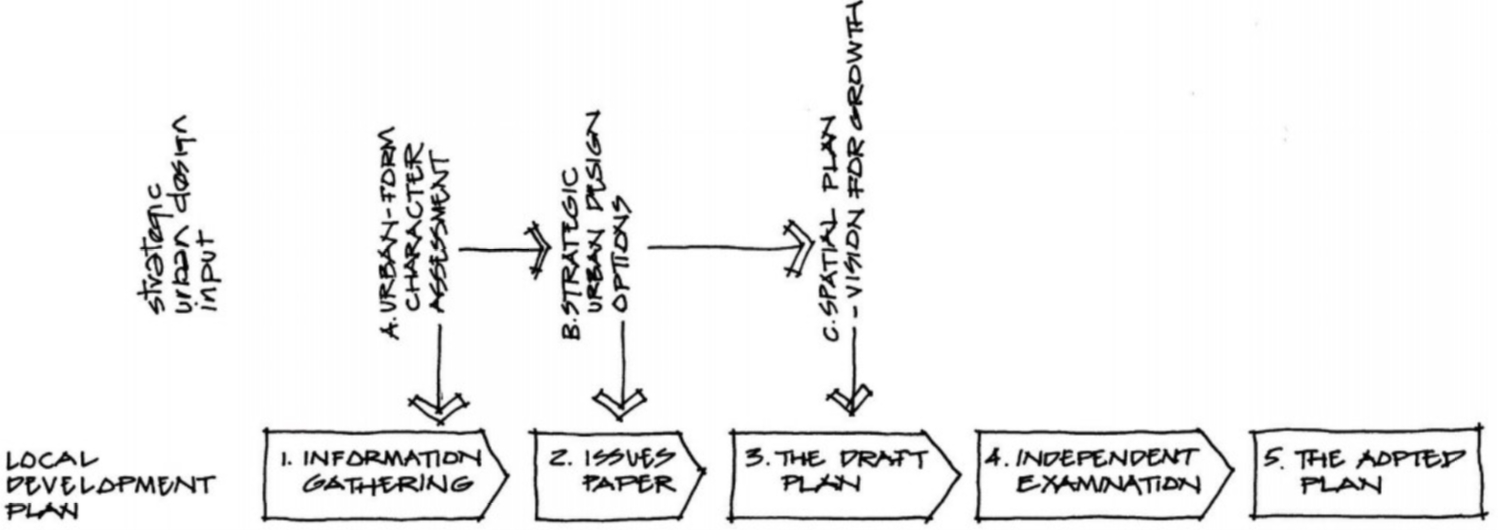

| Possible urban design input to a local plan. |

Contents |

Introduction

In 1994, when design was just re-emerging on to the planning agenda, the government of the day launched its ‘Quality in Town and Country initiative’. Towns and cities were invited to bid for funding to drive design-led planning studies and 21 locations were chosen for these ‘exemplar’ projects. One of these was Worcester, where the city council was looking to produce guidance for a large area in decline between the city centre and the River Severn. As a youngish and enthusiastic urban designer, I was delighted to be commissioned to work with the city council on the project.

A defining encounter

As a high-profile project, there was much interest from local civic groups and others. An extensive round of consultation was arranged. One of the bodies to be consulted was the local archaeological team. It was a defining encounter. I had expected to mark up a constraints map with remnants to preserve and sites to avoid, but what I found was a history extending back to medieval times which did not simply offer curiosities to conserve but urban forms that were as relevant for lives today as those that were lived six centuries back.

Street patterns that responded to the underlying topography, while providing what we might now call ‘permeable’ layouts; a public realm that had scales conducive to something between home zones and a 20mph zone; and a grain of plot subdivisions that offered a rhythm of frontages that catered for local traders: mixed-use, multi-functional, traffic-calmed, sustainable and wonderful – with the addition of modern sewerage.

It is the streets and public places that naturally endure the longest of a city’s components, while buildings of significance need protection if they are to survive beyond their amortisation period. Many historic market towns and city quarters were planned, but others evolved as human usage shaped human habitats. These are now some of the most valued urban environments, protected as conservation areas or even world heritage sites. People flock to them, as holiday destinations, valued city quarters or exclusive places to live.

If we know what such places look like, why are new developments so overwhelmingly banal? Every drab commuter estate built over the last 20 years has received a planning consent based on a near 100-page design and access statement and an environmental assessment. Over the next decade the government plans to build three million new homes. With supporting infrastructure, the footprint will be around 90 square miles, roughly the size of Surrey. Do we need to dumb down when planning for housing? Not at all: virtually every historic city began as housing. Houses served many functions before the advent of offices and specialised places of work. Streets were our common ground in both a geographic and spiritual sense. In town and city centres they served as market places and exchanges.

The local plan process

There is a perception that urban design is an activity that takes place once the local plan has identified development sites. But by that time half the urban design decisions have inadvertently already been taken.

The local plan process relies heavily on a ‘call for sites’, whereby local authorities invite land owners to propose sites for development by submitting an Ordnance Survey map with the land offered for development outlined in red. Sites are then assessed to see which have the fewest constraints or objections. There then follows a lengthy and expensive inquiry process where the preferred sites are incorporated in a plan in order to meet perceived development needs. It is a spreadsheet exercise which tends to grow towns by adding development pods to a town rather than considering the form of the whole settlement.

Strategic urban design

There is a widespread need for an understanding of urbanism to inform our local development plans. Sometimes referred to as ‘strategic urban design’, such considerations are often place-specific rather than topic-based. They take account of topography, seeking to grow settlements by watersheds rather than arbitrary ownership boundaries; they propose movement structures that are the focus and essence of the town rather than distributor roads that simply connect allocated sites rather like a plumbing diagram might join up random appliances; and they create neighbourhoods which are focused around the most important streets and avenues in the town rather than looking inward to the centre of a land ownership.

There is an historical dimension too. Growth areas are often part of a settlement with a long history and characterised by particular local development patterns, perhaps responding to micro-climate or socio-economic considerations. These may be as important in influencing new development as architectural detail or local building materials.

Many local authorities are short on design skills. Where urban design posts exist, the focus is often on the front line in dealing with developer planning applications and seeking to negotiate a better outcome for a site that is already allocated. So where can design skills be found to feed into the local development plan process? The answer may often be in the conservation team. Conservation officers are skilled in preparing character assessments of the built environment, have an appreciation of development scales ranging from the neighbourhood to the individual plot, and have a deep understanding of development as a continuum. As someone once said, if you want to know where we are going, study history.

Yet too often these skills are restricted to the consideration of existing conservation areas and listed buildings. I have lost count of the number of conversations I have had with friends and neighbours who have encountered a rigorous but objective ride on a planning application for a listed building or within a conservation area by dedicated and informed staff, yet are baffled as to why a dismal major development is springing up nearby.

There is a good argument for moving design and conservation teams into the mainstream of the development plan process rather than just servicing development control. From a local authority chief officer’s perspective, the conservation team is an existing, managed and skilled resource that could be brought into the work-flow of local plan production. If there is a budget to hire an urban designer, the conservation team can provide a base rather than a designer trying to be useful but with little support.

Strategic urban design inputs from the conservation team can be of great value in preparing both local plans and action plans:

Shaping the local plan

- Urban form character statements at the information gathering stage

- Strategic urban design options at the issues paper stage

- Contributing a vision for growth to the draft plan

Action plans

Rather than using conservation and design skills solely to meet the legal requirement of addressing conservation area and listed building, let’s bring design and conservation into the mainstream. How do we want to shape the 90 square miles of new housing over the next decade? If you want to shape the future, study history!

This article was originally published as ‘Bring on the conservation team’ in IHBC's Context 158 (Page 48) in March 2019. It was written by Roger Evans, a former chair of the Urban Design Group, an architect and urban planner specialising in urban design.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Membership Journal Context - Latest Issue on 'Hadrian's Wall' Published

The issue includes takes on the wall 'end-to-end' including 'the man who saved it'.

Heritage Building Retrofit Toolkit developed by City of London and Purcell

The toolkit is designed to provide clear and actionable guidance for owners, occupiers and caretakers of historic and listed buildings.

70 countries sign Declaration de Chaillot at Buildings & Climate Global Forum

The declaration is a foundational document enabling progress towards a ‘rapid, fair, and effective transition of the buildings sector’

Bookings open for IHBC Annual School 12-15 June 2024

Theme: Place and Building Care - Finance, Policy and People in Conservation Practice

Rare Sliding Canal Bridge in the UK gets a Major Update

A moveable rail bridge over the Stainforth and Keadby Canal in the Midlands in England has been completely overhauled.

'Restoration and Renewal: Developing the strategic case' Published

The House of Commons Library has published the research briefing, outlining the different options for the Palace of Westminster.

Brum’s Broad Street skyscraper plans approved with unusual rule for residents

A report by a council officer says that the development would provide for a mix of accommodation in a ‘high quality, secure environment...

English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023

Initial findings from the English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023 have been published.

Audit Wales research report: Sustainable development?

A new report from Audit Wales examines how Welsh Councils are supporting repurposing and regeneration of vacant properties and brownfield sites.

New Guidance Launched on ‘Understanding Special Historic Interest in Listing’

Historic England (HE) has published this guidance to help people better understand special historic interest, one of the two main criteria used to decide whether a building can be listed or not.