Main author

Michael BrooksOwen Hatherley - Trans-Europe Express

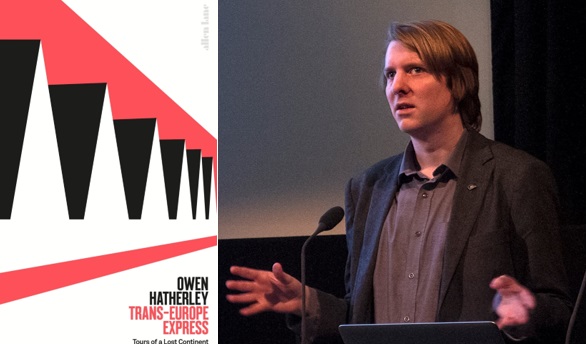

Owen Hatherley - 'Trans-Europe Express: Tours of a Lost Continent'

Published by Allen Lane (June 2018)

Over the last ten years, Owen Hatherley has been something of a tour de force in architectural criticism, publishing erudite and insightful content at a rate that would put most writers to shame.

Designing Buildings Wiki first interviewed Hatherley here in 2015 about the publication of his epic 'Landscapes of Communism'. Since then he has published 'The Ministry of Nostalgia', about the aesthetics of austerity Britain, and 'The Chaplin Machine' about the Soviet avant-garde. He returns to architecture and urban planning with 'Trans-Europe Express', a book which sees him exploring a disparate collection of cities - Dublin, Bologna, Hull, Bergen, Split, etc. - in the search for the elusive answer to the question 'what is a European city?'

In this wide-ranging interview, Hatherley explores and elaborates on some of the city-specific issues he addresses in the book, gives his current thoughts on the state of development in London, has some characteristically scathing words for the writer Simon Jenkins, and suggests that this book could mark the end of his 'urban explorations'...

|

Michael Brooks (MB): You’ve been strikingly prolific in terms of output over the last few years. Does it feel like you are in a particularly productive mode at present? |

Owen Hatherley (OH):

The two books on cities for Verso came out of a series of journalism for Building Design, this one came out of the Architects’ Journal, ‘The Chaplin Machine’ came out of my thesis, so they all grow out of something I’ve done journalistically or other work.

One of the reasons why my writing tends to find its place in book form is that a lot of architecture magazines don’t want my sort of writing. They want buildings to be reviewed and given star ratings, which I don’t find a particularly interesting way of looking at buildings or at cities. For example, if you search ‘Manchester’ on Archdaily, you’ll find lots of buildings by famous people like Foster, Libeskind and Calatrava – none of them very good. But there are loads of amazing buildings in Manchester by the likes of Harry S. Fairhurst, Leach Rhodes Walker, and so on.

|

MB: You open the book in Southampton – your hometown. How did that city shape and influence your views on urbanism? |

OH:

I feel bad talking about Southampton so much because I’ve not lived there in so long; I moved to London in 1999. In some ways it’s changed quite positively, like many cities in the South it’s lacking in identify and self-confidence. That’s offset by the fact that people from the surrounding area – Waterlooville, Romsey or wherever – see it as the big city, which has had a positive effect. Politically, it has always been good at certain things; when there was a Tory council for one term which was bringing in swingeing cuts, particularly to public sector jobs, there was a city-wide strike and it was defeated.

In architecture and planning it has always been third-rate. I developed a taste there for things being architecturally mixed, which it is in Southampton, much more so than a completely historic city like Winchester or a totally modern city like Basingstoke, both of which are nearby and which I find vastly more boring.

|

MB: I was interested to read about Sweden’s Million Programme in the 1960s that came out of very laudable aims. And yet, now they are in the midst of a prolonged housing bubble which people are blaming on precisely those sorts of policies – oversupply, rent regulations, capital gains tax on property sales, and so on. Can it be said to have been successful overall? |

OH:

It depends on what one considers a success or not. There’s a guy I quote in the book from Stockholm who says that ‘the city’s slums are better than Hampstead’. And they are, the housing there is lush compared with even quite upper-middle class British housing. If the aim of the Millennium Project was to build housing that was good, and let at non-market rents to people who needed it, it succeeded and Stockholm on that level is quite well-housed.

The problem it has is that it’s massively overheated at its core and that it’s been very speculative. Previously public institutions – lots of the housing associations that built the Millennium Project – have been encouraging the speculation and are building what is basically market housing which sells for stupid amounts of money.

I don’t really see it as a failure of regulation, more that the Swedish governments over the last 20 years have thought it would be a good idea to inflate a property boom in the centre of Stockholm. Because Sweden is still so regulated and still has a reluctance to dismantle what’s built, one of the intriguing things is that the institutions of social democracy are building neo-liberalism in Stockholm in a way that does have similarities to what New Labour did – PFI, marketisation of public services, all done from the top down.

But maybe those who live in Sweden and complain about their housing situation should be forced to live in London for 6 months.

|

MB: The similarities you draw between Dutch and British cities are very interesting, but also the distinctions – you say that ‘people made Dutch cities better’. Why haven't people made British cities better? |

OH:

I think they have actually, but it’s more about whether it’s with or against the grain. This is the thing eco-urbanists point out all the time - if you look at how Amsterdam and even Rotterdam became so friendly to cyclists and have great public transport, etc., people seem to think it’s because of their morphology – they’re full of narrow streets and that’s why it’s like that. Which is total nonsense –you look at photographs of Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the early-1960s and they are as choked with traffic as anywhere.

What happened was that people tried to curb and limit that and tried to expand public space; expanding pavement into the road, expanding cycle lanes, lots of subtle things like that. They were able to get the ear of local government – collections of hippies and Situationists like the Provo Movement had a lasting influence on urban policy, which was never true here to the same extent.

Mostly the main influence of the 1960s on British cities has been to create a demonised image of modernist planning which was then enormously useful for Thatcherism. Its positive achievement is fuck all, whereas the positive achievement of 1968 in somewhere like the Netherlands is that it has very pleasurable public spaces, cycling and public transport.

London is probably the city that has gone furthest towards this. I don’t think Londoners fully appreciate this; its public transport system is far superior to that of any other British city. The social city never really happened in London but what there is, is places like Elephant and Castle which are usually the result more of the fact that the market has failed to produce something like a Westfield or Brent Cross; instead of which it became cheap enough that people in the very multi-cultural surrounding area were able to use it as a social space.

The fact that it has been able to be saved on the basis of it being appealed on equality law was really interesting – they argued that what was intended to be built in its place had no provision for the minority ethnic groups or the elderly that use it. I thought that was incredibly astute that they used that line of attack and I hope it’s used much more often.

|

MB: Last time I interviewed you in 2015, you were quite pessimistic about the state of London’s development. In light of Elephant and Castle and things like the Haringey Development Vehicle, are you slightly more optimistic now? |

OH:

Vastly more optimistic. I’m quite impressed at how much people in London have stopped taking shit, I think it’s great. This is hard to prove, but each of those two things you mentioned are right next to huge developments that got built, so we know now what it means.

In 1997, you could say to people ‘in the future you’ll be rehoused in a lovely new development on the same ground which will be nicer housing, nicer high street, and your life will be better, we might have to use private developers to do it but the proof will be in the pudding’. Well, now we’ve eaten the pudding, and the pudding is shite, the pudding is 40-storeys of largely empty luxury flats.

The Heygate redevelopment is utterly scandalous. Nine Elms up the road in the next year or so will be a scandal on the same level at Centre Point was in the 1970s; they’ve built something the size of a small town which is empty, because they’re building for people who are investing here in order to hide their capital from a global crisis.

Certainly in Haringey people could see what happened at Woodbury Down and Stratford, and so could say ‘this is not for us’. The wankers – Peter John, Alan Strictland and Claire Kober – of course still say ‘this is for you, you’re in the way of development which is going to make lives better for people’, but ‘these people’ that they are talking on behalf of can see that the empty flats in front of them are not for them. So on an empirical level, people can see that it’s bollocks.

|

MB: In the section on Vyborg you write about ‘the acrid stink of history rather than the waxy, varnished smell of heritage’. The conflict between these two conditions – can they be resolved in some kind of happy medium? Even if an Old Town is, as you say, ‘ruthlessly restored and furnished with Costa Coffee’, isn’t that better than it being left to decline? |

OH:

One of the reasons why Bologna (see image above) is in the book is the fact that a lot of those middling Italian cities have a lot of preservation and it doesn’t feel Disney-like. One of the things about places I go to that I quite like but feel a bit uncomfortable in, like the old town in Stockholm, is the sense that everything has been freeze-dried and sand-blasted and all life removed, which is quite depressing and often has an aspect involved of removing the poor from them a lot of the time.

There is not a lot I would credit Italian planning for, their record over the last 100 years is not great, but being able to have historic centres that are quite relaxed is one of them.

|

MB: Is it possible to draw a loose parallel between the great plans in Skopje – which you call a ‘stark vision of contemporary priorities’ – with the post-1960s clash in the UK between the traditionalists of the Prince Charles mentality and the modernists? |

OH:

Simply put, no. What’s so obvious with Skopje is that what they’re doing is encasing the modern buildings in a fake classicism – you’ve got a Corbursian post office that’s got fibreglass Corinthian pilasters put over it. There is no sense of juxtaposition or balancing of these things, instead it’s about erasure.

It would be hard not to be nostalgic for the 1960s in Skopje; you’ve got somewhere that’s gone from being one of the most open and daring places on Earth to being a place that basically bills itself as a kind of Disney theme park geared almost entirely by the avarice and philistine ideas of gangsters and warlords. However much one might want to criticise the sclerotic bureaucrats of Tito’s Yugoslavia; better that than gangsters and warlords, which is what we’re talking about here.

Needless to say, it looks like a very cheap attempt to achieve a banal luxury. My interest in that is that it’s a mirror image of what a lot of traditionalists seem to want, which is a reconstructed version of a historic city that in this case never actually existed. It’s based on denying the actual history of the city which is one of the one hand, defined architecturally by the Albanian part of it, and the city it was in the second half of the 20th century – a cooperation between Japanese, pan-Yugoslav, Swiss, American and French architects who were attempting to build a city for a country which considered that it was building an experiment for management socialists. The new city is based on making sure that people never think that that was possible, they were never able to do that and participate in those sorts of ideas. I can’t think of many things more grotesque than Skopje really.

When they were protesting there a year ago, one of the things people were doing was throwing paint at these ridiculous buildings and monuments because they see them as being the reason for their dispossession.

I’m quite sure at some point Simon Jenkins will discover Skopje and talk about how brilliant it is, and how anyone who doesn’t like it is a snob, which is why he should never be allowed to write about architecture ever again.

|

MB: I was struck by there being a lack of people in the book, there’s no account of the lived experiences within the urban environments you explore – what it’s like seeing or using a particular building every day. Was that a conscious decision? |

OH:

With Skopje that was necessary because of the fact that it’s one of those places where you could so easily fall into the look of being the person who beams down from Western Europe and goes to the Balkans and says ‘oh it’s so uncivilised’. So I was quite keen to talk to Macedonians who also thought it was disgusting and who were spending their waking hours trying to fight it.

But I don’t ‘vox pop’, if anyone is interviewed in the book it’s because I know them. Other people can ‘vox pop’, there’s Olly Wainwright for that.

|

MB: It’s nearly 10 years since the publication of your first book ‘Militant Modernism’ – have you got big ideas for the next 10 years – exploring new urban environments around the world perhaps? |

OH:

I’d rather do a lot more historical stuff that involves going into archives. That would be in terms of books, in terms of journalism there’s still a lot to argue for, and now there’s the novelty that to some extent I’ll be listened to, whereas over the last 10 years, certainly the first few anyway, there was never any sense of that.

Now, I think there’s an openness to ideas on housing and planning by people who could end up in government so I’m very keen to influence that in any way that I can. In terms of 'walking around and looking at things' books, I don’t want to do them anymore, I feel like I’ve done what I set out to do. This and the book coming later in the year will be the last, after that I will do something else.

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard V1 published

Free-to-access technical standard to enable robust proof of a decarbonising built environment.

Prostate Cancer Awareness Month

Why talking about prostate cancer matters in construction.

The Architectural Technology podcast: Where it's AT

Catch up for free, subscribe and share with your network.

The Association of Consultant Architects recap

A reintroduction and recap of ACA President; Patrick Inglis' Autumn update.

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.