Main author

Michael BrooksLost Utopias - Interview with Jade Doskow

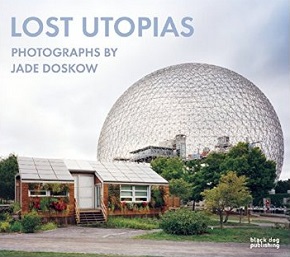

Jade Doskow - 'Lost Utopias'

Published by Black Dog Publishing (2017)

This wonderful new book presents images taken over ten years of documenting the crumbling and derelict World's Fairs sites across America and Europe. Photographer Jade Doskow's images document the strange abandonment - or as she describes it, the 'limbo-state' - that many of these sites fall into, in sharp contrast with their once pioneering ambition.

The images are contextualised by essays from the English photographer Richard Pare and American academic Jennifer Minner, together with a glossary of the World’s Fair sites. The book raises questions about the future of these sites, the significance of their architecture, and what place, if any, they have in today’s society.

Designing Buildings Wiki put some questions to Jade Doskow about her career, what drew her to these fascinating structures, and how she approaches the art of architectural photography:

| Designing Buildings Wiki (DBW): How did you get started in photography? |

Jade Doskow (JD):

My parents encouraged an appreciation of the fine arts my entire childhood, and I spent hours drawing, but I was late to photography and fell into it while attending New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study in the late 1990s.

In between classes I was working as a New York City bike messenger and got into a pretty bad crash. While recuperating and taking several photography courses I experimented with a series of self-portraits and interiors that ended up winning an award at NYU, causing me to realise that perhaps there was potential in this new medium to create something meaningful.

Through working as a darkroom printer in a prestigious lab in NYC I also learned about large-format photography, the exquisite detail and luminosity possible specifically through this sub-genre within the medium, and specifically large-format architectural work, as some of the masters in the field would bring their pictures to be printed there.

| DBW: What was it about the expositions that drew you to them as a photographic subject? |

JD:

In 2004, I was traveling in Seville, Spain with family. We traveled across Calatrava’s bridges to the other side of the Guadalquivir River, and to the semi-abandoned site of the 1992 World’s Fair (expo).

It was extremely curious to me that they would choose this as a stop on the bus route. There were empty flagpoles clanging in the wind, a fountain filled with algae and beer cans, and acres and acres of semi-abandoned postmodern expo buildings, some in use, some overgrown. Despite the haphazard state of the site, this was clearly a point of pride for the history of modern Seville.

I was immediately intrigued, and upon returning to New York began researching the history of World’s Fair. Fast-forward to graduate school in 2006 (the School of Visual Arts in New York) and I had the academic structure in which to begin the work in earnest. What I discovered was a remarkably meaty subject, a cross-disciplinary tour-de-force bringing together elements of historical world events, art and culture, technology, racial strife, industry, architecture, design, and nationalistic pride, all pushed for maximum effect into the design of exhibitions and pavilions constructed for World’s Fairs.

What was most fascinating was the seemingly arbitrary treatment the sites received after the fairs closed, often with little or no vision into what would happen to these structures and landscaped sites, often unwieldy and constructed of little-known, cutting edge materials.

| DBW: In terms of their architecture, what is it about the structures that sets them apart from others? |

JD:

Most architecture is designed for some semblance of ‘permanence', and the pavilions designed for World’s Fairs were the opposite; elaborately conceived designs for a highly specific, temporal period of time, usually six months or twelve months over two years.

The World’s Fair architecture embodied highly specific ideals and ideas of the future through its design, whether the neoclassical temple-like structures of the 19th-century to the stripped classical of the 1930’s to the wildly fantastic, space-race influenced architecture of the mid-century fairs, such as Philip Johnson’s New York State Pavilion or the Atomium in Brussels.

The fair sites are prisms through which to view these past dreams and goals of the future, a sort of time travel in a public park. There often was not a lot of planning as to what would happen to these structures after the fairs closed. While many structures were sold off and shipped elsewhere or dismantled and sold for parts, there were the odd remnants, a giant Calder sculpture, the New York State Pavilion, the Parthenon in Nashville, that became a different part of the urban fabric as they aged and changed over time into the unforeseen ‘future.’

It is this complexity that I find greatly appealing, the completely arbitrary nature of how these sites and structures evolve into our contemporary world; they are case studies for urban planning and historic preservation, ultimately a questioning of what we choose to preserve or discard on our shared urban sites.

| DBW: What was it that drew you to architectural photography in particular? |

JD:

I was always quite sensitive to the specific aura of place, the way light filters through windows and skylights, the sounds through the windows or silence, the way a street or square or park resonates around me.

This is perhaps in no small part due to the magical environments of my childhood: the 300-year-old-farmhouse I grew up in, the walls held together with mud and horsehair; my grandmother’s small apartment in the Bronx overlooking the graffiti-covered subway lot; the luminous loft down on the Bowery in downtown New York; my great-aunt’s antique-filled Cape Cod on Long Island, surrounded by thick forest, delicate rare flowers growing at the foot of the looming trees.

In 2003, I moved to the waterfront neighbourhood of Red Hook, Brooklyn. Closely studying the vernacular architecture of the neighbourhood and how light transformed or subdued specific blocks and buildings, I diligently photographed long-abandoned shipping warehouses, wood-frame houses, vacant lots, hand-painted church signs, often returning to the same building or block over and over.

Architecture, in the sense of photographing architecture, is sculptural, time-based, and ephemeral despite its plasticity, therefore echoing parallel characteristics to photography. A building can appear dull, flat, moulded, dynamic, sinister, or beautiful, all depending on what quality of light is shaping it and what perspective it is being approached from. Add to that the puzzling out of how to correctly represent perspective and it is a creative and dynamic challenge like no other kind of photography.

I enjoy and thrive on this challenge, as well as assessing carefully how a piece of architecture exists in its current environment and how the cityscape around it has responded - or not - to its existence.

The common thread, at this point, through all of my work, is the idea of the limbo-state of architecture. Other than when a building is freshly built and being used exactly how it was envisioned to be used, the patina changes, the purpose of the facility changes, the environment around it changes, the industry no longer exists - ultimately all buildings are objects we create for the purposes of our time and how we live life now.

While there are icons and marvels of architecture that have stood the test of near-contemporary time, it is simply impossible to predict the life of a piece of architecture. So I look at photography, arguably a completely imperfect tool of ‘documentation,’ and use this medium to approach architecture, human-made creations that reflect and repel our goals, dreams, and activities in society, and illuminate that complexity, of how these echo-creations of who we are exist now, and how this existence is a continuum, a clashing of past-present-future.

| DBW: What do you find the most challenging part of being an architectural photographer? |

JD:

A good architectural picture exists at the intersection of location in space, weather conditions, the capability of the equipment and photographer, and access.

Lack of access can be frustrating, for obvious reasons. Light is tricky as well, as I am working with natural light. On a shoot in Charlottesville, VA, I waited for about five hours for a break in the clouds to take the picture; as I’m shooting large format, I was just a fraction of a second too slow and missed the shot anyway.

Shooting large format film is slow and painstaking work, the opposite of shooting with an iPhone or even a DSLR. There have been times it took me a half hour to set up the shot and then an unforeseen obstacle would prevent me from creating the picture. But I thrive on this frustration; it is what makes the successful pictures that much more satisfying.

| DBW: Is there a building you would really like to get a chance to shoot? |

JD:

Many! I would love to photograph any of Zaha Hadid’s buildings, due to their innately sculptural and highly dynamic qualities, it would be a pleasure to spend some time, specifically the MAXXI museum in Rome. And long on my bucket list: everything in Brasilia, a place spiritually and conceptually parallel to the Lost Utopias work.

You can purchase Lost Utopias here.

All photographs © Jade Doskow

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Anthony Weller - Architectural photographer.

- Architectural photography.

- Grant Smith - Architectural photographer.

- Habitat 67.

- How to commission architectural photography.

- Interview with Paul Grundy - Architectural Photographer.

- Photographing buildings.

- Simon Kennedy - Architectural Photographer.

- Space Needle.

Featured articles and news

UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard V1 published

Free-to-access technical standard to enable robust proof of a decarbonising built environment.

Prostate Cancer Awareness Month

Why talking about prostate cancer matters in construction.

The Architectural Technology podcast: Where it's AT

Catch up for free, subscribe and share with your network.

The Association of Consultant Architects recap

A reintroduction and recap of ACA President; Patrick Inglis' Autumn update.

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.