Floors of the great medieval churches

Mosaics, patterned tiles, stone paving and commemorative stones are among the treasures that can be found underfoot, needing to be appreciated and protected, in Britain’s great churches.

|

|

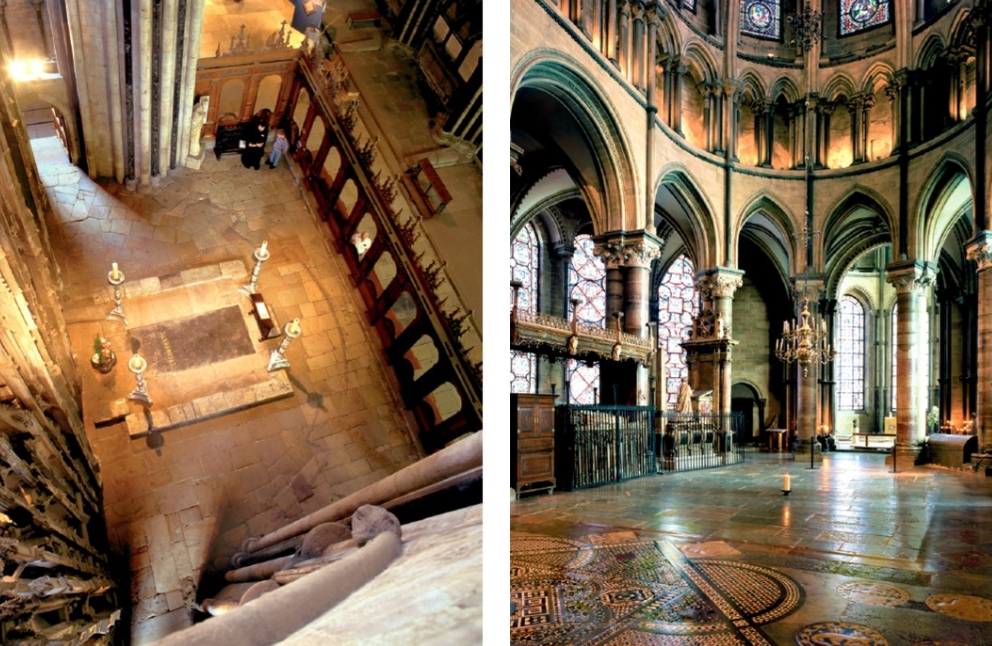

Photos copyright John Crook (http://www.john-crook.com) The floor of Canterbury Cathedral’s Trinity Chapel with roundels (right) which were probably relaid in the 1180 and (left) the feretory (area where relics were kept) at Durham Cathedral. The Durham paving preserves the layout of the Romanesque apses. |

As we enter a great church our eyes are inevitably drawn upwards to arches, vaults, ribs and sculpture. Feasting our eyes on these treasures, we are all too prone to ignore the ancient floors beneath our feet. But if we do look down, we will see a variety of types of medieval floors, including intricate mosaics, patterned tiles, stone paving and commemorative ledger stones.

Medieval floors have suffered a great deal. Commemorative slabs were inserted into earlier pavings. New fashions have had a massive impact, with old paving swept away to accommodate patterned marble floors and, in the Victorian period, encaustic tiles. Worn pavements can be ruthlessly replaced.

Nevertheless, a good deal of medieval flooring remains, albeit but a fraction of what once existed. The Ashmolean possesses a tile with a raised relief pattern dating from c1000-1050, which was found near Oxford Cathedral. At Durham, a medieval pavement survives on the platform where St Cuthbert’s shrine stood. The layout of the first phase of sandstone paving stones preserves the apsidal form of the original east end dating from the 1090s. The platform was enlarged and squared up when the Chapel of Nine Altars replaced the original east end. The additional paving stones are smaller and slightly paler, although still formed of the same sandstone.

The especially sacred areas of great churches could be adorned with particularly ornate and splendid floors. William of Malmesbury, a contemporary, stressed the beauty of the marble pavement of the early 12th-century choir of Canterbury Cathedral. The choir was destroyed by fire, but according to Christopher Norton parts of the pavement were relaid in the 1180s to form the surround to Becket’s shrine.

The most impressive and costly floors created in medieval England are the ‘Cosmati’ pavements at Westminster Abbey, the finest of which is found in the sanctuary in front of the high altar. The pavement has been described as one of the pre-eminent works of art of medieval England. Unlike mosaics, where the stone pieces are all small cubes, Cosmatesque designs feature materials of different shapes fitted together to make a pattern in a style developed in Italy in the preceding two centuries. The materials included decorative stones (marbles and porphyries) and glass, laid in a bed of mortar. Some of the stones were acquired from Roman-period archaeological sites and re-cut to form the pieces. This intricate 13th-century mosaic floor lay hidden under carpet to protect its fragile surface, away from public view for over a hundred years, until a two-year restoration project (2008–10) by the abbey brought it back to life.

In the north of England another, less expensive form of geometrical mosaic pavement was introduced in the 13th century in Cistercian monasteries. This consisted of a combination of different tile shapes with alternating colours to bring out the geometry of the design. The best surviving examples come from Byland Abbey. Some are in situ, and a number have been reassembled in the British Museum.

In the south of England a different tradition – two-tone tiles inlaid with designs – was preferred. They were first commissioned by Henry III in 1237 for the now lost St Stephen’s Chapel at Westminster, and subsequently for his palace at Clarendon, near Salisbury. Parts of pavements from the king’s and queen’s chambers in the palace were transferred to the British Museum under the supervision of Elizabeth Eames, who curated the museum’s collection for many years. Under her supervision they were displayed on the floor of a specialist tile gallery but they have since been removed to the walls of an all-purpose medieval room. The tiles were made by impressing a wooden stamp in the red clay body of the tile, infilling the impression with white clay, glazing and baking.

Henry III’s finest inlaid tile pavement remains in situ in his chapter house at Westminster Abbey. Completed by 1258, the tiles contain 36 different designs, some of superb draughtsmanship, but altogether forming a unified pattern. Laurence Keen described the pavement as ‘without any doubt, the most important surviving example in Europe’. It has survived so well since the room was covered by a wooden floor after the Reformation when it was used as a record office. It was revealed and restored by Gilbert Scott in 1863. Some years ago it was possible to walk on it in felt slippers, enjoying to the full the experience of this magnificent floor, but the slippers have had to be abandoned in favour of matting.

Medieval tiled floors continue to be rediscovered. One of c1300 was found in 1987 in the library at Lichfield; the complete medieval design has been recovered. In 2015 a floor at Exeter Cathedral was uncovered by the cathedral’s archaeologist, John Allan, during renovation work. It is in a room above a chapel, which in the middle ages was used as the Exchequer and in the 20th century as the Song School for boy choristers. It had probably been boarded for over a century, and no one alive had ever seen it. Allan observed that round the edges, where it had not been walked on by decades of feet, the glazing of the tiles was still intact and they looked as if they were new.

After Westminster Abbey, the retro-choir of Winchester Cathedral contains one of the most important spreads of 13th-century floor tiles in the country, including large areas where the original ‘carpet’ scheme has been preserved. Wear caused by visitors’ feet risked eventually causing the complete obliteration of the tile patterns in unprotected areas. As some of the tiles were loose, a number were stolen; a tile said to come from Winchester Cathedral was sold at auction in the 1980s. The Winchester pavements have now been restored. While some problems could not be rectified, the tiles look magnificent.

Such inlaid tiles were widely used in great churches, for example in the muniment room at Salisbury. A number of the most famous series include those of c1350 depicting Tristan and Isolde and Richard the Lionheart and Saladin from Chertsey Abbey. A tile from Tring shows a schoolmaster striking the young Jesus. The tradition of inlaid tiles continued into the 15th century with a particularly fine collection at Great Malvern Priory. Here the floor tiles have been lifted and fixed to the walls, along with original wall tiles.

While ornamental floors were laid in the chancel and east end, in other parts of the church floors were often laid with paving slabs, commonly of Purbeck marble. Even specialist accounts of medieval floors have tended to give little attention to such paving. Purbeck marble survives from the 13th century at Salisbury and from the 14th at Winchester, where the remains of Bishop Wykeham’s nave floor remain. Among the best survivals is the floor of Chichester nave, which retains almost 40 per cent of its 12th-century Purbeck paving, laid in a characteristic diagonal manner.

The Chichester floor pavement also contains several ledger stones inserted into an earlier floor, some of which had been moved there from the choir. ‘Ledger stones’ are flat, incised, commemorative stones, and are among the oldest and most common of sepulchral monuments. They became increasingly common in the later middle ages. More prestigious and expensive were the stones with inset brasses which first appeared in the 13th century, of which in many cases only the stone settings now remain. After the middle ages ledger stones proliferated and are now to be been seen in huge numbers.

In the 17th century the continental fashion for chequered marble pavements was copied. Hooke and Busby, the headmaster of Westminster School, worked together on the black-and-white chequer-board pavement in the choir of Westminster Abbey in the 1670s. Subsequently, Wren laid a similar floor at St Paul’s. In the 18th century attention turned to repaving the naves of great churches. In 1786 it was agreed to repave the nave of Canterbury in Portland stone lozenges. In 1789–90 the original paving in the nave and aisles of St George’s Chapel, Windsor, was replaced, although fortunately there is a drawing by John Carter of the earlier nave in 1783, which seems to have consisted of foot-square Purbeck marble paving, set diagonally.

Floors continue to be relaid, and threats to ancient floors remain, both from the feet of increasing numbers of visitors and from poor decisions. In about 1980 the floor of the nave of St George’s, Windsor, was relaid again. Unfortunately, cheaper options were chosen. Tim Tatton Brown observed in 2005: ‘After 25 years, one can only regret that the decision was taken (in around 1979) to use the cheapest “York stone” in “random courses” with a “sawn finish”’. Instead, he argued, the Painswick stone paving of 1788–90 should have been restored or repaired.

Another conundrum is confronted regularly at Westminster Abbey. The nave of the abbey was paved (with both Purbeck marble and Purbeck stone) between 1510 and 1517. Much of this paving remains, although it has been much cut into by later ledger stones. But the floor has suffered from the inevitable desire to commemorate national figures at a national church. The cost has been the continuing loss of stones from this important medieval floor. An increasing appreciation of our surviving medieval floors implies that modified approaches will need to be made in this instance and at other great churches.

This article originally appeared in IHBC’s Context 152, published in November 2017. It was written by David Harrison, a retired House of Commons clerk and medieval historian. In the House of Commons he served in many positions, including as clerk of the environment, transport and regions committee. He has published many articles on medieval architecture and transport. His book on The Bridges of Medieval England was published by OUP in 2004.

Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Angstloch.

- Archaeology.

- Bridge chapel.

- Britain's historic paving.

- British Museum.

- Building a Crossing Tower: a design for Rouen Cathedral of 1516.

- Cathedral of Brasilia.

- Chapels of England: buildings of protestant nonconformity.

- Coal holes, pavement lights, kerbs and utilities and wood-block paving.

- Cologne Cathedral.

- Conservation.

- Cosmati work.

- Encaustic tiles.

- Flagstone.

- Floorscape in art and design.

- Florence Cathedral.

- IHBC articles.

- Medieval architecture.

- Oubliette.

- Palace of Westminster.

- Penarth Alabaster.

- Prothesis.

- Purbeck marble.

- Slype.

- St Pauls Cathedral.

- St. Basil's Cathedral.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Types of floor.

- Vicars' close.

IHBC NewsBlog

Old Sarum fire in listed (& disputed) WW1 Hangar - Wiltshire Council has sought legal advice after fire engulfed a listed First World War hangar that was embroiled in a lengthy planning dispute.

UK Antarctic Heritage Trust launches ‘Virtual Visit’ website area

The Trust calls on people to 'Immerse yourself in our heritage – Making Antarctica Accessible'

Southend Council pledge to force Kursaal owners to maintain building

The Council has pledged to use ‘every tool in the toolbox’ if urgent repairs are not carried out.

HE’s Research Magazine publishes a major study of the heritage of England’s suburbs

The article traces the long evolution of an internal programme to research 200 years of suburban growth

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.