Purbeck stone

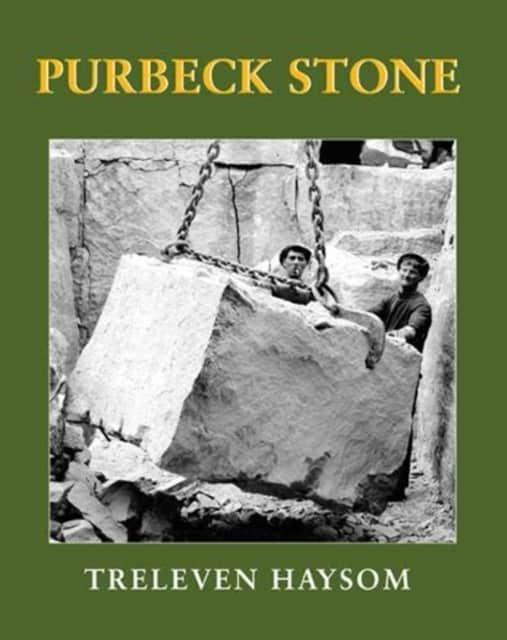

Purbeck Stone, Treleven Haysom, Dovecote Press, 2020, 312 pages, over 350 colour and black-and-white illustrations, hardback.

For those of us who have not spent a lifetime working with a particular building material, the next best thing is to learn from someone who has. Treleven Haysom is the 11th generation of his family to have worked in the stone industry on the Isle of Purbeck, Dorset. His book is a chance to immerse ourselves in the stones and their uses.

Why did the quarrymen rarely whistle? ‘My father thought the aversion to whistling lay in the fact that sometimes as a ceiling bed separates there can be a sucking sound,’ Haysom writes. ‘It was something best to be on the alert for.’ Knowing what you were doing in this dangerous industry could be a matter of life and death. Most beds were hacked out from below, the upper beds being supported by leaving just enough stone in place, or building supporting columns and walls.

Accessed from the cliffs or by digging down, the beds produce a variety of types of stone that is wide in both quality and thickness. Thicker beds provide building stone, while shallower ones are suitable for paving and the thinnest for roofing.

Much Purbeck stone is a warm, yellowy-brown colour when it is first quarried, weathering to a softer, greyer tone. Many of the rocks were built up from the sediment of a few species of clams, oysters or snails, which can be seen clearly. Many (much more than those of nearby Portland) are also characterised by calcite veins, locally called ‘lists’, caused by stress to the rocks over millions of years. The caption to one of the photos refers to another type of stress: ‘Note nearest long roofing slab, heavily distorted by dinosaur trampling.’

The stone from beds of so-called Purbeck marble are hard and polishable, although many other Purbeck beds that are equally hard and polishable are known by other names. The darker marbles were particularly valued for their decorative uses in medieval architecture.

Haysom is particularly good at explaining the specialised language of the quarrymen, some of which changed in meaning over the years. By the end of the book the reader will find that a quoted comment such as ‘Ruggle ’im round on banker til the back’s lookin’ at yer, then tother side’s the face’ makes perfect sense.

He explains how the various stones perform in buildings. Used locally, the stone in this seaside location tends to become saturated by salt, whose crystals damage the stone by expanding in confining pores. ‘If fully exposed to drenching rain the stone lasts well,’ he writes, ‘but, paradoxically, if somewhat sheltered, damage occurs.’

The author draws on a lifetime of quarrying and masonry work, a deep knowledge of the industry’s working and oral traditions, and years of research. The story is well told in immense and fascinating detail, and superbly illustrated with photographs, maps, diagrams, plans, paintings, drawings and engravings.

This article originally appeared as: ‘Trampled by dinosaurs’ in Context 169, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in September 2021. It was written by Rob Cowan, editor of Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.