Heritage and urban design in Tamaki Makaurau / Auckland

Note: Regrettably, the macron line that should appear above the vowel 'a' in some parts of this article is not available within the text editor on Designing Buildings Wiki.

Auckland is expected to account for 70 per cent of New Zealand’s population growth in the coming decades, much through urban densification. How will its heritage cope?

|

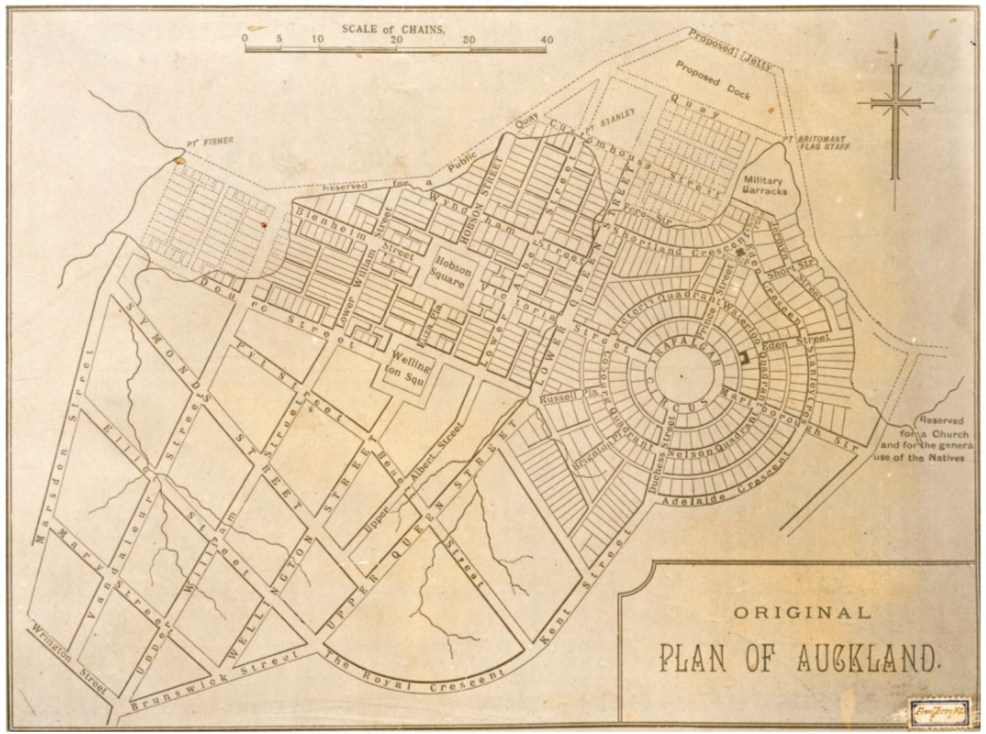

| Felton Mathew’s Original Plan of Auckland, 1841 (Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries). |

As the last major landmass to be settled by humans, the urban heritage of Aotearoa/New Zealand is a remarkable juxtaposition and layering of natural features, successive settlement groups with imported cultural outlooks and evolving transport technologies. In November 2020 the Bloomberg Covid Resilience report placed New Zealand at the top of the global Covid rankings. In 2019, Auckland came joint third in the Mercer quality of living survey. There must be some truth to the hype: one third of the country’s five million people likes Auckland enough to call it home.

This popularity is nothing new. Auckland’s Maori name, Tamaki Makaurau (one translation: ‘the land desired by many’) reflects its attractiveness to successive settlers from the earliest days of human habitation (around 700–800 years ago). A temperate climate, fertile soils, abundant resources to support the development of an indigenous material culture and easy access to a coastline teeming with fish: who wouldn’t want to live here?

Auckland’s geography is unique. The city sits on a narrow isthmus formed by volcanic eruptions over the last 100,000 years, with the most recent only 600 years ago. This volcanic activity has gifted Auckland an indented coastline with east- and west-facing harbours, making it ideal for shipping and trade. The Maori cultural landscape features around 15 significant portages, allowing waka (canoes) to cross between west and east coasts and to link to major internal waterways to connect throughout the country. Many of our early colonial heritage sites are coastal and the sense of being constantly at the edge of water is one of Auckland’s features.

These geographical attributes were not lost on early European settlers. In 1841 Governor William Hobson chose Tamaki Makaurau as the capital of the new colony, with its Pakeha (non- Maori) name Auckland in honour (supplication?) of his patron the Earl of Auckland (who never came anywhere near here). It retained this status until 1865, when the capital moved to Wellington. Hobson is best known for preparing Aotearoa/ New Zealand’s founding document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi, which was signed by British representatives and Maori chiefs in 1840. While ostensibly aiming to provide a stable, bi-cultural foundation to the new country, key differences in the English and Maori translations have caused significant pain since 1840.

As the capital of the new colony, Auckland needed a town plan. Surveyor general Felton Mathew was engaged for this task. Having grown up in Bath, he adapted his hometown’s crescents, circuses and avenues to fit into the volcanic landscape, with a new plan published in 1841. Felton Mathew’s plan failed to be built in its entirety, but a walk around Auckland’s city centre streets provides a roll-call of 19th-century British luminaries: Victoria, Albert and Pitt Streets were all built under this plan. Due in part to this early growth, more than 10 per cent of Auckland’s scheduled places are in the city centre. Heritage outcomes are enshrined in the Auckland City Centre Master Plan (CCMP), which was refreshed in 2020 [1].

As Auckland grew steadily during the 19th century, its growth was shaped by its transport infrastructure, which meant water. For most of human history (and particularly for island nations) people and goods travelled by sea. This is particularly true here; the Auckland to Wellington railway line was only completed in 1908. From 1859, new quays were built in Auckland city centre on reclaimed land, typically obtained from dynamiting the nearest sea cliff, as at Te Rerenga Ora Iti/Point Britomart. Most of the flat land in Auckland city centre is reclaimed. Some of the finest Edwardian buildings are found on reclaimed land, including the Ferry Building and the Chief Post Office.

Auckland’s natural stone is a combination of soft sandstone and very hard volcanic basalt. The latter, while unpleasant to work, is ideal for kerbstones. These were originally mined by prisoners in what must have been relentlessly unpleasant conditions. Hand-cut and machine-cut basalt kerbstones have proven highly durable and can still be seen in parts of Auckland city centre.

A revolution in Auckland’s urban form came in 1902 with the first electric tram (just one year after London), followed by a spiderweb of new lines. With cheap transport, suburbia boomed along these lines, shaping many of Auckland’s most attractive suburbs: Remuera, Epsom, Mt Eden and others. At its peak in the 1940s the Auckland tram system carried 100 million passengers per year; not bad for a city with just 250,000 people. With modern transport and a growing population, the city centre and inner-city suburbs boomed. Heritage buildings from interwar Auckland include the art-deco Civic Theatre and St Kevin’s Arcade, the Chicago-style General Buildings and the neo-gothic Auckland Electric Power Board Building.

Similar to American and Australian cities, Auckland’s tram system connected walkable suburbs with a bustling city centre. From the late 1940s, transport planning increasingly took its cue from the USA (specifically Los Angeles). The tram system was completely dismantled by 1956, to be replaced by an urban motorway plan that Paul Mees describes as ‘almost hysterically anti-public transport and pro-motorway… even by the standards of the 1950s [2].’ The subsequent decline in public transport use was more precipitous than in almost any other major city. A brutal urban ring motorway displaced 15,000 people during its construction and effectively severed the central and inner city from its surroundings, a problem that remains today.

As suburbanisation continued into the 1960s and 70s, Auckland’s city centre entered a period of relative stagnation. The absence of extensive development provided a respite to many of its fine city centre heritage buildings. This stability received a major shock in the 1980s as New Zealand underwent ‘Rogernomics’ (broadly equivalent to Thatcherism or Reaganomics). This saw supply-side measures to unblock the economy, with a loose money supply and deregulation.

With cheap money sloshing around in an atmosphere of exuberant entrepreneurialism, a commercial property boom erupted throughout the country, most intensely in Auckland city centre. Demolition of unprotected heritage buildings proceeded at a frightening pace to make way for mirror-glass skyscrapers. Heritage protection in this era was often down to good luck. The party came to an end with the early 1990s recession, by which point many fine buildings had been lost. The Royal International Hotel was demolished in 1987, shortly before a major stock market crash. Its site has spent most of the intervening 33 years as a surface car park; a painful hole in the urban fabric.

Maori heritage fared even worse, due to a lack of official recognition by successive iterations of colonial and dominion machinery and decision-making. Auckland’s maunga (volcanic cones and features), long-venerated by local tribes, were viewed as a good source of aggregate by Pakeha quarrymen. Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi, signed in good faith in 1840, gained formal recognition in New Zealand law only in 1975. A 1985 amendment gave it greater legal weight, including with respect to heritage protection.

Government involvement in heritage dates from the 1950s, with the establishment of national heritage agency Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, which now manages a list of over 5,600 entries. The list includes specific entries for Wahi Tapu and Tpuna (Maori sacred sites), reflecting New Zealand’s bicultural founding. Heritage in Auckland is managed through the statutory Auckland Unitary Plan.

Understanding both of heritage and Aotearoa/ New Zealand’s bicultural approach to its management has increased since the turn of the 21st century. Auckland Council’s Maori design hub has been created to enable best practice in architecture and urban design. The ongoing transformation of Auckland’s downtown waterfront public spaces is a good example of Maori design in practice.

If Felton Mathew were to return to Auckland today and take a walk down Albert Street, he would find his path disrupted by construction of City Rail Link (CRL), a $4.4 billion, twin-track, four-station underground railway line. This is New Zealand’s largest ever transport infrastructure project. CRL construction saw all 14,000 tonnes of the Edwardian Chief Post Office (CPO) transferred to a supporting structure to allow rail tunnels to pass beneath it. When open, the CPO building will serve as a gateway to the rail station and the city centre, continuing an intelligent approach to re-use.

Another CRL station will be built at Karangahape Road. Running east-west along a ridge above the city centre, this was the only street for which Felton Mathew deigned to use its existing Maori name; a reflection of its long-held significance. Once the heart of middle-class Aucklanders’ department store shopping life, Karangahape Road lost its economic hinterland in the 1960s to motorway construction. Department stores gave way to strip clubs and economic activities on the margin of the mainstream. The area was viewed with a lack of interest by developers.

This meant that Karangahape Road escaped much of the swathe of 1980s development. Businesses in the area tended to re-use and adapt existing buildings. Today the area is home to over 600 owner-occupied businesses and an intense concentration of heritage buildings. As one of central Auckland’s two historic heritage areas, it arguably has a greater sense of place than anywhere else in Auckland and, when CRL opens, it will be one of the city’s most accessible locations. This provides an opportunity for many more Aucklanders to get to know the area; it also means a challenge for the area to retain its uniqueness and heritage in the face of change.

This is a citywide issue. Undeterred by property prices that resemble Monte Carlo, Auckland attracts people through job opportunities, an enviable lifestyle and fine weather. The city is expected to account for 70 per cent of New Zealand’s population growth in the coming decades. Much of this is likely to be met through densification of the existing urban fabric, with old houses on large plots demolished and replaced by townhouses or flats. Will new buildings be able to enhance the sense of place? Where do we most need to maintain our heritage? And how can we enable the special character areas of the future? These are going to be important questions for Auckland and Aucklanders in coming years.

References:

- Auckland CCMP (2020) Outcome 8: Heritage-defined city centre www.aucklandccmp.co.nz/outcomes/outcome-8-heritagedefined-city-centre/protecting-our-uniqueheritage/

- Auckland City of Cars (2006) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sCKDBHT3i74

This article originally appeared in Context 167, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in March 2021. It was written by George Weeks, a principal urban designer in the Auckland Council urban design unit, who is responsible for the refreshed Auckland City Centre Master Plan.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Architecture and Urbanism in the British Empire.

- Commonwealth Heritage Forum.

- Conservation.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Manual of Contract Documents for Highway Works.

- Masterplanning.

- Sheep and Dog Buildings, Tirau.

- The conservation of historic transport infrastructure.

- Town planning.

- Urban design.

IHBC NewsBlog

Old Sarum fire in listed (& disputed) WW1 Hangar - Wiltshire Council has sought legal advice after fire engulfed a listed First World War hangar that was embroiled in a lengthy planning dispute.

UK Antarctic Heritage Trust launches ‘Virtual Visit’ website area

The Trust calls on people to 'Immerse yourself in our heritage – Making Antarctica Accessible'

Southend Council pledge to force Kursaal owners to maintain building

The Council has pledged to use ‘every tool in the toolbox’ if urgent repairs are not carried out.

HE’s Research Magazine publishes a major study of the heritage of England’s suburbs

The article traces the long evolution of an internal programme to research 200 years of suburban growth

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.