Understanding context

Rethinking how to reform the planning system and get the construction industry working effectively depends on urban designers’ skills in understanding context.

|

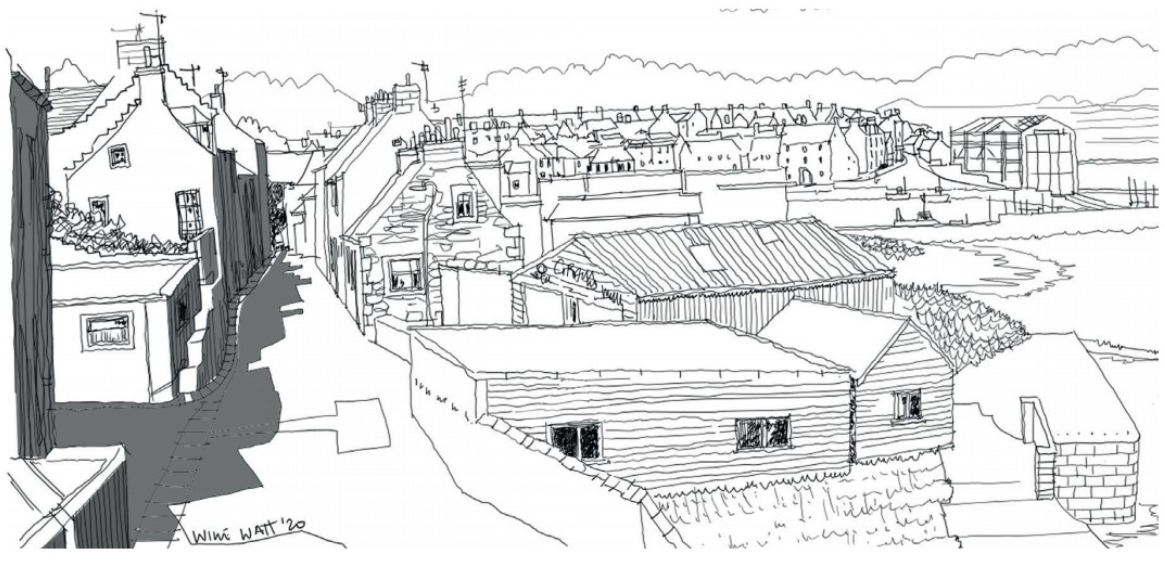

| A context sketch of St Monans, Fife, by Willie Watt, architect and master planner of Nicoll Russell Studios, Dundee. Sketching by hand uses a part of the human brain that helps develop a unique understanding of space, spatial hierarchies and character that cannot be acquired by photographing or computerising imagery. |

Contents |

Introduction

Britain’s built environment has seen better days. The quality of design has decayed. Sustainable development has been difficult to achieve. Local authorities have suffered a huge loss of skills and resources, but the pro-active planning lobby requires both. Placemaking, considered the best vehicle to achieve sustainability, is not always evidenced in planning applications; rather, a vast number of submissions lack contextual analysis, adequate depth of information and design integrity. Built-environment education seems polarised towards two distinctive strands: first, a tight understanding and adherence to rules; and, second, idealistic utopias difficult to deliver. Design schools are progressively diverting from contextual cognitive learning to producing striking imagery with futuristic tools, a promising glossy world of practice that attracts paying students but results in a loss of skills.

The problems in the industry are systemic, poor outcomes being largely due to how all the parties involved interact. An effective way to move forward would involve a holistic understanding of the context in which built environment professions operate. That context involves big issues like climate change, health and wellbeing, housing, welfare, equality and inclusivity, all of which transcend both geographical and scholarly boundaries, and which require system-thinking and collaborative, pragmatic approaches. Positive change requires a change of model.

Imagine an engine whose pieces can be removed and repaired individually. Current legislation operates like that, considering all specialities separately. Now imagine an ecosystem whose components are connected by the processes that associate them, rather than by their individual qualities. An organic, systemic approach that focuses on the relationship between the parts, their relative hierarchy and the way in which they affect each other would seem far more plausible as a model for the future of planning.

Conversely, the parts of the industry are heading in different directions, failing to reconciliate their goals and motivations, or to deliver a common agenda. Professional bodies are insular, having self-regulated codes of practice that emerged from old models like the engine that we imagined, which are no longer appropriate. In response to such an archaic ethos, higher education bodies offer technological advances and complex software solutions that promise a future of construction allegedly capable of eliminating errors by automatising design processes. The danger is that improved tools applied to the old model will continue to exacerbate problems, but do it faster than before.

Unbalanced context analysis

Sustainable development involves three spheres: economic, environmental and social. Economy is captured in monetary terms, so there is a measure: gains can be assessed and investments can be value-engineered. The capitalist system probably contributed to the growth of the economic sphere at the expense of the other two. To compensate for this imbalance, professionals have tried to measure the economic gains of ecology. For example, they have looked for evidence of how removing parking and providing street trees can attract shoppers, or how property values can be raised by increasing access to green spaces. The social sphere is rarely dealt with at all. Applying monetary currency to the environmental sphere only results in the transference of these non-economic gains on to the economy sphere, increasing its relevance and devaluing the other strands further.

Some might argue that quantifying social and ecological variables such as heritage, culture, nature, beauty, health and wellbeing could risk enabling savings in those areas. Conversely, the failure to quantify these eliminates their accountability altogether, making asset reduction or loss a less threatening prospect. This lack of accountability has left social and ecological fields arguing for agendas that respond to their specific ethical motives, but without much leverage.

An accidental outcome of this imbalance is that built environment students lack sufficient exposure to all three strands of sustainability in equal measure. Take the field of architecture, for example: course accreditation criteria largely reflect a focus on the building as an object, and an overall tendency towards form and tectonics, only considering an understanding of impact in a course’s later years. However, the socio-environmental crisis we face dictates that designers must begin with an understanding of place. A comprehensive initial analysis of context and the ecosystem of the setting should precede the architectural design, which is always another component of a larger, complex system. Only then should the philosophical and technical description of architectural objects follow. This much-needed shift in paradigm, from object-in-space to component-of-place, is crucial to sustainability.

Course validation criteria disregard staff development in areas where other fields of expertise overlap with architectural practice, and limit the number of external visiting board members from other disciplines. Ironically, collaborative approaches would anticipate that specialisms outside the realm of architectural practice have important roles to play in shaping an architect’s mind.

Obsolete methodologies are not exclusive to architecture. Some urban design courses focus on form-first master planning. This may be a naive attempt to validate the relevance of urban designers as technical specialists, as necessary as architects but working at a different scale. While some architects can master plan, urban design practice requires different skill-sets and, more important, a different mindset.

Specialist skill-sets of urban designers:

Working

- Within political frameworks

- Negotiating to add value

- Based on evidence

- Bridging theory and practice

- Joining disciplines and communities

Understanding

- Society and human behaviour

- Policy and ownership

- Design and form

- Economy and value

- Natural environments

Thinking about

- Human needs first

- Systems and processes

- Spaces between buildings

- Long-term changes

- Context and culture

The built environment requires a cultural change that goes beyond the use of emerging technology and the application of complex tools. It is time to question the role of each specialism and how they relate.

Radical reform

As radical as the white paper ‘Planning for the Future’ might seem, change will not happen by application of logics that did not work before. The reform will be meaningful if it is accompanied by a cultural change that emerges from a clear understanding of the context in which all built environment fields currently operate.

The main issues are:

- The mechanistic engine model was adopted to resolve the problems of modernism. Today’s problems require an ecosystem approach.

- Innovation must focus on resolving the issues of the system, looking at how fields of expertise relate, rather than developing further field-specific tools.

- Achieving sustainable development requires levelling-up the economic, environmental and social spheres, developing a sphere-specific way to measure outputs.

- Regulatory frameworks within planning must focus on governing accountability, and making every party responsible for increasing capital in all three strands in equal measure.

- Legislative frameworks must have a clear emphasis on relations, hierarchies and synergies, rather than focusing on outputs. Delivering place quality requires an understanding of how things happen, more than looking at what will be delivered.

- All component parts within the system and all fields of expertise should be reviewed, at all levels.

The first step should focus on the regulation of built-environment education, investing in a robust long-term multi-disciplinary reform. There is wide recognition that the UK planning system is not working, that it became obsolete some time ago and that new models are required. The pandemic has given the whole world an opportunity to reflect, rethink and create an improved ‘new normal’. When doing so, we must not forget that in any project, no matter how large or small, the quality of contextual analysis is always what makes the difference between success and failure. Resolving the built-environment crisis is not an exception to this rule: we must understand what we have in order to plan what to do.

This article originally appeared in Context 167, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in March 2021. It was written by Laura Alvarez, senior principal urban design and conservation officer at Nottingham City Council.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?