The story behind The Guide to Building Materials and the Environment

In 2008, I was with Stephen George + Partners. SGP were commissioned to design a sustainable construction training and research centre for a consortium of bodies including North West Kent College. As well as providing a space for education, the building itself was to be designed as a teaching resource, providing examples of low energy design, utilising a wide range of sustainable materials to demonstrate their potential. My team’s task would be to oversee the technical resolution of the design in accordance with sustainable principles. We set about investigating the sustainable credentials of every major element we wished to incorporate in the eventual design. Our research began to provide some interesting and often surprising results. Against expectations, we sometimes found that a material we initially considered as being one of the most environmentally friendly was not quite what it appeared. On the other hand, many widespread and commonly used materials turned out to have quite good environmental credentials by default.

What we did find was that, although a material may be undeniably sustainable, the way we procure and construct buildings rendered its use unviable. Higher degrees of risk, limited availability, increased costs, lack of site skills combined with an inherently conservative building industry all conspired to add increasingly burdensome constraints on our selection of materials.

Having acquired a large amount of data, some of which we felt was not commonly known within the architectural profession, we felt it a shame not to collate this in a form which would be of some practical use. My then colleague, Jo Denison and I, therefore (with the blessing of SGP’s partners), decided to put together a guide which we would make freely available to help other professionals seeking to navigate the minefield of sustainable design. Hence in 2010, we published the Stephen George & Partners Guide to Building Materials and the Environment.

Thankfully our efforts seemed to be well received and as we had never intended the Guide to be a static work, after a relatively short period, published a second edition incorporating much information which had become easier to obtain thanks to our new-found fame! It was this work which, in 2011, was nominated for and won The RIBA Presidents Award for Outstanding Practice-Based Research.

It is now, of course over ten years since the original version of the Guide was first published.

Much has happened in the intervening period. After my highly fulfilling time at Stephen George + Partners, I moved to work in a different sphere of architecture for several years. With the social, political and economic upheavals of the past decade, sustainability seemed to take a backseat within the world’s economy for a time in the face of more ‘immediate’ problems. However, the environment has a way of providing nasty reminders of how vital it is to our existence on this planet.

Then just a few years ago, I started receiving enquiries once again about sustainable design. Faced with a host of world-wide extreme weather events, a fuel crisis, pollution and a realisation that the effects of climate change were indeed now upon us, attention has once again turned to focus on sustainable design to provide solutions. This upturn in interest prompted me to contact my former work colleagues at Stephen George + Partners and, between us, we agreed to produce a new, fully revised third edition as a collaborative project. The altruistic basis of the Guide as being free to all was to be maintained and to further cement its collaborative principle, we asked both CIAT and the GreenSpec website for help to promote our efforts. To complete the team, Norse Consulting, where I now professionally reside, came on board as supporters of the project. As a widely inclusive publication, the Guide no longer sits with just SGP but is intended to be promoted by the whole group for the wider good. We decided to therefore shorten the title to A Guide to Building Materials and the Environment. It is in this form that the third edition of the Guide was launched in Summer 2023.

Recent geo-political and environmental events have spurred on a resurgence in the market for sustainable materials. However, this has not made selection of these easier – far from it. With the expansion of the ‘green’ market and manufacturers’ attempts to capture a greater proportion of it, has arrived the concept of ‘Greenwash’. Claims and counterclaims employing only a selective focus are widespread. When I began to revisit the last edition, I was shocked at how much had changed in a relatively short space of time. The increasing frequency of extreme floods, droughts, storms, heatwaves and forest fires seems to have begun to finally focus establishment attention on what we might have done to our planet and the consequences of this do not lie in some far-flung future but are becoming very real here and now. Added to this a fuel crisis and ongoing material shortages are creating a greater demand for low impact and sustainable solutions.

Developments in concrete technology (for example) have moved from the niche to the mainstream and the composition of insulation materials has come under intense scrutiny due to the tragic events of Grenfell. When we wrote in the first edition about the Great Pacific Plastic Sargasso, its existence was not widely known. Today it is relatively common knowledge — to the point where single use plastics are beginning to be banned in many countries. Some technologies though have fallen by the wayside. Touted as the ‘next big thing’, they failed to attract funding for further development. This unfortunately speaks volumes on our present economic system and the value attributed to sustainability.

What I think has become apparent, to those considering the problems of sustainability, is that issues cannot be addressed in isolation. For example, one may think that end-of-life options for a material may be a basic requirement. But this is often ignored - even in respected rating systems such as BREEAM. There is no point in stating something is ‘recyclable’, if no-one is recycling it! So ‘who, how and where’, are more important questions than ‘can it’. The very term ‘recycling’ is a misnomer. Most materials are not actually used again in the same manner, but are really ‘downcycled’ via yet another industrial process, e.g. plastic bottles become clothing.

Consider that, 300 years ago, every material available would be a product of nature. There were no industrial processes available to produce synthetic materials such as plastics. Consequently, everything would be expected to eventually decay or be reused in either a new building or in another capacity. Today, life without artificially produced materials is almost unthinkable. However, the plastics we produce and use today will be in the environment forever. A vast area of the Pacific Ocean is now known as ‘The Plastic Sargasso,’ and has become choked with the discarded remnants of plastic consumer goods. Even the much-heralded introduction of biodegradable plastics should be viewed with some suspicion as the decay process for these is far from proven outside the laboratory. Construction is second only to the packaging industry as a producer of plastic waste and far from reducing the amount consumed, between 2019 and late 2021 actually increased its plastic waste output by almost 46%. This continued the trend for the four years up to 2018 when UK construction increased its plastic output by over 69%.

Transport of materials is also still a largely unresolved issue. As regards the contribution to the carbon footprint arising from transportation from abroad, again very little definitive information is available. The UK Environment Agency has produced a freely downloadable Carbon Calculator for assessing the embodied energy of both materials and the construction process. This allows one to assess the emissions arising from transportation by road, rail or water. Generally speaking, waterborne options result in about a 90% reduction of the emissions arising from road transport with rail being between the two. Although shipping of materials in bulk would seem to imply an economy of scale which results in low emissions per unit, the scale of the shipping industry in our global economy has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years. Cargo vessels use the dirtiest and most polluting oil available for fuel in addition to which accidental spills of bulk goods and fuels contribute to increasingly polluted oceans. Greenpeace have estimated that the emissions associated with global shipping may be larger than those arising from the aviation industry.

However, there is at present no real effort being made to assess, quantify and control carbon emissions from shipping, which remains largely immune to most international climate change agreements. In the Tyndall Centre’s 2010 report entitled Shipping and Climate Change: Scope for Unilateral Action, it is pointed out that the method of calculating the carbon emissions from the UK’s shipping traffic may be flawed and these may be up to six times the level currently stated. Transport of materials has minimal impact on environmental accreditation systems such as BREEAM or LEED. In some versions of LEED, points are available for materials sourced within 500 miles! Of course, in the context of North America, this may be considered relatively ‘local’.

Our aim in the third edition of A Guide to Building Materials and the Environment, as it was originally, is to provide access to enough objective information to enable selection of materials with the least harmful impact. Again, we cannot provide answers – merely a starting point for enquiry.

Section 1 gives an overview of some of the issues associated with specifying sustainable materials, while an overview of individual materials will be found in Section 2 together with links to external sources of information. Section 3 comprises data sheets summarising advantages, disadvantages, considerations and sustainable alternatives for each material.

In Britain (and across much of the developed world) we have the initiative of ‘net zero’, and in Scotland, the Passivhaus standard has recently been adopted as the norm for new housing. However, despite all this, there is still no UK legislation covering the embodied carbon or general sustainability of materials. Most of the focus continues to be on operational energy. This does not mean it is a subject not being addressed – far from it. In fact, the often-spurious sustainable credentials of materials seem to be a prime vehicle for unscrupulous marketeers to employ in a quest for sales. This practice has become known as ‘Greenwash’, and is one of the main aspects for specifiers to be aware of. The only way to avoid this is knowledge. Hence, I believe, the continuing need for this work. Without truly understanding the impact of our actions, through an intelligent selection of materials which will not damage the environment, can we ever hope to leave our descendants a planet which will support their continuing survival?

Downloadable from the website of Stephen George + Partners, our aim is to make the Guide widely available as possible and so should, in the near future, be available from a number of sources such as GreenSpec and Norse Consulting also. As an ever-evolving source of information, we intend to produce regular (hopefully quarterly) updates and addenda covering any recent developments. The first of these is on the verge of being published as I write.

Finally, we always have encouraged feedback with reference to the Guide and would welcome any constructive comment or input to future editions.

This article appears in the AT Journal Winter 2023, Issue no 148 as "The Guide to Building Materials and the Environment", written by Chris Halligan MCIAT, Chartered Architectural Technologist.

--CIAT

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Composites.

- Construction materials.

- Deleterious materials in construction.

- Materials.

- Metal in construction.

- Phase change materials.

- Sustainable materials for construction.

- Guide to Building Materials and the Environment published

- Types of materials.

- Types of biobased materials.

- Use of ceramics in construction.

Featured articles and news

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

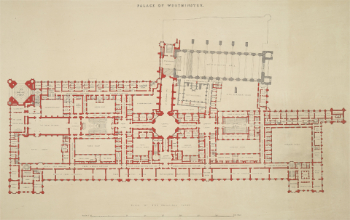

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

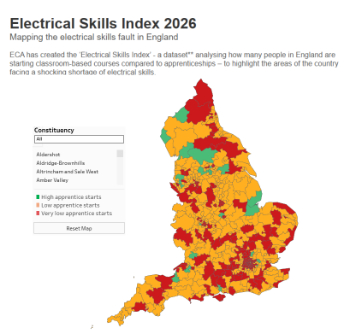

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.