The impact of the design of the psychiatric inpatient facility on perceptions of carer wellbeing

Authors: Wood, V, J., Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Spencer, I., H., Close, H, J., Mason, J., Reilly, J, G.

The background and context in which the research was carried out

This paper is based on qualitative research that was carried out by researchers at Durham University as part of a wider NIHR funded evaluation of the provision of a new psychiatric inpatient facility in Northern England. The study focussed on the transition from an old to the new hospital building, and on views of patients, carers and staff about how the building design and setting of the old and new facilities related to their perceptions of wellbeing.

Here we focus on the experiences of ‘informal carers’, the family and friends who provide care to people with mental health conditions. Carer’s experiences of mental health care settings are important because they often play an essential role, not only in providing care in the community but also in care of patients during periods of hospitalisation. UK strategies which support carers also acknowledge the important role that carers play as ‘essential partners in the treatment and recovery process’ (Worthington and Rooney, 2010, p.2).

Hospital building design can make a big difference in terms of facilitating or restricting family access, social ‘engagement’ and ‘connectedness’ (Schweitzer, Gilpin and Frampton 2004, pp. 72-73). Psychiatric hospitals have been described as ‘spaces of transition’, intended to prepare the service user to return to life in the community by encouraging a degree of connection between the community and the clinical environment (e.g. Curtis et al 2008; Quirk, Lelliot & Seale 2006). The design and environment of mental healthcare hospitals therefore not only needs to create a therapeutic environment which facilitates the wellbeing of the patients and staff, but it needs to be equally conducive to the wellbeing of those who provide informal care, by providing a ‘permeable’ (Curtis et al 2008) and accessible environment for the family and friends who care for patients from within the wider community.

In order to explore the impact of the design of the psychiatric inpatient facility on perceptions of carer wellbeing we have used the idea of the carer’s ‘journey’ to and through the hospital space. We explored the extent to which the hospital space is experienced by carers as one that is ‘permeable’, inclusive and accessible and their sense of whether the hospital provides a therapeutic environment. Our research makes an original contribution to the wider literature on hospital design, standing alongside a more in-depth version of this article which was recently published in Social Science & Medicine (Wood, V, J. et al) and which also makes a significant contribution to research in geographies of health concerning ‘therapeutic landscapes’.

The methodology adopted and the work completed

At the start of the study, psychiatric services were being provided in the ‘Old Hospital’ established in the late 1800s, with an original design that was typical of the late 19th century asylums, and in two acute mental health wards at the local ‘General Hospital’ at a different location. While our research was progressing, construction was completed of the ‘New Hospital’, a modern psychiatric inpatient facility. Service users were then transferred to the ‘New Hospital’ and the ‘Old Hospital’ was closed down.

Our approach was based on similar techniques that had been used previously (Curtis et al., 2007, 2008) in a different location, and is broadly consistent with what Gatrell (2002) identified as a social interactionist methodology. The methods used were interviews and discussion groups in which we asked participants to give their views on what aspects of the Old Hospital and New Hospital were good or bad for the wellbeing of those using the facilities. We talked to some participants twice, once before and once after psychiatric services were relocated.

The sampling procedure used to recruit participants was purposive. This was obtained through key contacts previously made at the hospital, and with the assistance of the Patient Advice Liaison Service (PALS) and other organisations providing services to patients and carers at the hospital and in their community. The material used in this paper on carer experiences was drawn from interviews and discussions with carers, patients and staff, and includes one carer group discussion, two carer interviews and one staff group discussion all taking place either before or during the move to the New Hospital. After the move we then conducted one carer discussion, one carer interview, an interview with a senior carers support worker, one staff discussion and one discussion with a recently discharged patient (Wood et al, 2013 pp. 123-124).

Discussion groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were first considered independently by three members of the research team who made a thematic analysis of the aspects of the hospital design mentioned by respondents as important for wellbeing. A ‘therapeutic landscapes’ framework was used to categorise these into themes relating to the physical, social and symbolic dimensions of the hospital environment. Researchers then met to compare their analyses and agree on a consistent interpretation. Our interpretation of the key themes was then summarised and fed back to the participants and also presented at events and at policy and practice seminars organised through the NHS, at which local carers and service users were present.

Findings and conclusions drawn from the research

We considered the ‘journey’ made by carers when they visit the hospital and how they experience aspects of the built and social environments on the way.

Starting from home base and arriving at the hospital

The findings from our study highlight that the physical connection between the hospital and the carers’ local community is important for the ease with which they can maintain close contact with the person they care for. For instance, some carers expressed the importance of community services and hospital staff working together, to minimise the need for inpatient care. Carers who were relocating from the General Hospital also questioned whether a new hospital at a more distant location was cost effective. Public transport routes from their homes would be more complicated and they felt the cost of travelling would be burdensome. Staff also highlighted patient concerns about receiving fewer family visits, and how the longer traveling distance would restrict patients’ home leave and their ability to maintain links with their family. This concern was echoed in an interview with a recently discharged patient who told us about the difficulties that his wife experienced when she was visiting and the limited number of visits he received while he was in the hospital because ‘it was such a journey’. As they arrived at the New Hospital, the car park was also perceived to be ‘not very carer friendly’, with access for taxis dropping off being difficult and the ‘walk from the car park to the entrance’ causing ‘major problems for people who are disabled’.

The external appearance of the New Hospital building as they arrived was, however, often described positively by carers, using words such as ‘beautiful’, ‘inviting’ and ‘a good future design’. In contrast to the Old Hospital which was perceived to be stigmatising and often described in comparatively negative terms such as ‘overpowering’ and ‘out of Dracula’s time’. There was some concern about the way in which the New Hospital was now being described as resembling ‘a hotel’, which they felt would obscure the ‘positive work’ that carers were doing to try and de-stigmatise mental health.

The hospital entrance

The reception and entrance is the first point of contact when carers enter the hospital. In contrast to the Old Hospital, the senior support worker we interviewed suggested that for carers the entrance space at the new hospital was ‘a much better place to be, they’ve said they feel more comfortable walking into the building’. Despite this there was not always a receptionist on the desk to ‘meet and greet’ the carers when they arrived, which was important for those families who had never been there before and might be feeling distressed. There was a map giving directions to each of the wards, but she suggested that carers would feel more reliant on personal guidance to direct them through the hospital space: ‘…they will be looking for somebody to help them… it’s not like going to a shopping mall’. This challenges ‘consumerist’ notions of mental healthcare, while also expressing the need to make hospitals more permeable for carers, and in this sense, personal interaction seems to be equally important in providing a welcoming environment as a good design with ample signposting.

Entering the ward space

The next part of the journey through the hospital space involves gaining entry to the wards. While some modern acute inpatient units for mental health care now have unlocked wards, visitors coming into a ward are generally still screened by staff (Curtis et al., 2008). In all of the hospitals considered here the wards were permanently locked and nursing staff were the gatekeepers to ward entry and exit for all patients and visitors. While this is a measure intended to protect patients, it creates a sense of a subordinated position for carers and patients in the hospital space. Any measures making for ‘smooth’ passage through security barriers may help to reduce this impression.

The hospital did, however, seem to be moving towards greater support for carers, providing them with more information and fostering stronger and better relationships between carers and members of staff. For instance, running carers’ events, placing information on notice boards and identifying staff who would serve as carer champions on each of the wards, trained to provide information and look after them when they came to visit.

The quality of relationship between staff and patients was also important, with positive social interactions being said to make ‘a huge difference’ to how carers felt and the degree of distress and burden they often carry. As Gesler (2003, pp. 14-15) highlights healing can be considered as a social as well as medical process, and the quality of social relationships contributes to a therapeutic setting. Greeting patients and carers in a friendly way and taking time to talk to them was massively important. Carers of patients at the General Hospital also suggested that some continuity in the relationships that they had already developed with staff was an important part of making a successful transition to the New Hospital building.

Spaces for family and community living within the hospital

The organisation of space in the hospital provided important opportunities for activities which replicated family life and social activity in the community. These included private spaces for visiting, providing families with the ‘opportunity to talk in private’. On the wards of the New Hospital, however, there was no room specifically designed for private family visits, so these often took place in one of the quiet rooms, which were not specifically reserved for visiting and frequently used for other purposes. More generally, carers would sit in lounge area on the ward. However, several participants suggested that the acoustics in the New Hospital produced a high level of ambient noise in these areas, which was felt to create an uncomfortable environment for visiting.

One carer commented on how she would use the enclosed garden area to find a quieter more ‘relaxing’ space, enabling her to have the kind of conversation that one might have in a domestic garden, telling us ‘the gardens are all lovely’ and ‘it is a nice place to be in’. This was in contrast to the comments of other carers about the courtyards and garden areas of the Old Hospital which were felt to be ‘very oppressive’ and reminiscent of ‘a prison yard’. Thus highlighting not only how the gardens and grounds are important features of modern inpatient facilities, but also how in more general terms, carers and family members need to have access to a variety of different settings within the hospital.

As well as ‘homely’ settings for intimate and private family interactions, spaces offering opportunities for social gatherings similar to those found within a community setting were also felt to be important. For instance at the Old Hospital there had been an old recreational hall, a space run by volunteers and patients where ‘everybody can congregate on an evening’, providing opportunities for shared activities such as ‘table tennis and pool’. At the New Hospital there was no similar type of space, so this was ‘something that was missed’ by some of the carers. There was, however, a café that was publicly accessible, but this was not open in the evening and did not run social activities or events. Because the café was a commercial operation it was also more expensive and did not provide the same opportunities for patient involvement.

The only other type of publicly accessible social space within the New Hospital was the ‘Multi-faith space’. Although a space which allows service users to practice their religious belief together may in some ways be seen to be socially and spiritually important, some of the carers commented on how they felt the space was inadequate because ‘the room is not big enough’ and the presence of other faiths may be distracting due to differences in religious practices and levels of noise during prayer. As a result, they suggested they would have preferred ‘separate rooms for each faith, not just one place’.

Another part of the carers’ discussion also reflected a desire for the hospital to be consistent with one’s own neighbourhood ‘sense of place’. One carer who participated in one of the planning meetings for the New Hospital suggested that she had helped to choose some of the aesthetic features such as the decoration of the window glass on the ward. One option which designers proposed for the windows would have made reference to the immediate local area in which the hospital would be situated. The carer who was living in a different area told us how she voiced objection saying ‘this is not a [local area] service, it is a service for everybody’ and as a result ‘we just got a nice piece of flowery stuff on the windows’. Thus, it was important for this carer to choose a neutral design, symbolically inclusive for members of all the different communities using the hospital. Comments such as these emphasise carers’ desire for the hospital space to be reflective of the wider community and to allow community practices to permeate the hospital space.

In conclusion

Our findings suggest that as well as being aesthetically pleasing, safe and secure, it is important that the hospital environment be experienced as ‘permeable’, inclusive and accessible for carers to assist them in their caring role. A ‘permeable’ institution in this sense would be one that ensures:

- Accessibility to the site for visiting carers;

- Ease of movement across the interface between outside and inside the hospital;

- A ‘homely’ hospital setting, fostered through good relationships between hospital staff and carers, and peace and privacy to reproduce domestic practices;

- A design that is ‘inclusive’ of all groups using the hospital, and spaces within it that partly substitute for social and faith-based venues in their home communities and help to maintain kinship and friendship bonds

It seemed that the newly built inpatient facility for mental health care considered here offered these features to some extent, but the New Hospital could potentially have been made more permeable and accessible for carers by paying more attention to the interrelated material, social and symbolic aspects of the inpatient setting from a carer’s point of view. It would have been helpful if the hospital design and model of care were based on a stronger understanding of the ways in which carers experience the hospital setting, through dynamic engagement with the space linked to their caring role. For many mental health service users and family carers the hospital is the setting for extended or repeated periods of care, so it seems essential to explore how to enhance the therapeutic quality of the hospital setting from their point of view.

The findings presented here are based on a small sample focused on a single hospital in the UK NHS system so they are not generalisable, but it does provide a valuable basis upon which further study using a larger sample and focused more exclusively on carer’s experiences of hospital design in relation to wellbeing could be considered.

This paper was entered into a competition launched by --BRE Group and UBM called to investigate the link between buildings and the wellbeing of those who occupy them.

References:

- Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Fabian, K., Francis, S., & Priebe, S. (2007) Therapeutic landscapes in hospital design: a qualitative assessment by staff and service users of the design of a new mental health inpatient unit. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 25, 591- 610.

- Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Priebe, S., & Francis, S. (2008) New Spaces of inpatient care for people with mental illness: a complex rebirth of the clinic. Health and Place, 15 (1), 340 – 348.

- Gesler, W. (2003) Healing places. Oxford UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Quirk, A., Lelliott, P., & Seale, C. (2006). The permeable institution: an ethnographic study of three actue psychiatric wards in London. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 2105 – 2117.

- Schweitzer, M., Gilpin, L., Frampton, S. (2004) Healing Spaces: elements of environmental design that make an impact on health. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 10 (1). 71-83.

- Wood V, J., Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Spencer, I, H., Close, H, J., Mason, J., Reilly, J G. (2013) Creating ‘therapeutic landscapes’ for mental health carers in inpatient settings: A dynamic perspective on permeability and inclusivity. Social Science & Medicine, 91, 122-129

- Worthington, A., & Rooney, P. (2010). Triangle of Care, carers included: A guide to best practice in acute mental health care. National mental health development unit.

Featured articles and news

One of the most impressive Victorian architects. Book review.

RTPI leader to become new CIOB Chief Executive Officer

Dr Victoria Hills MRTPI, FICE to take over after Caroline Gumble’s departure.

Social and affordable housing, a long term plan for delivery

The “Delivering a Decade of Renewal for Social and Affordable Housing” strategy sets out future path.

A change to adoptive architecture

Effects of global weather warming on architectural detailing, material choice and human interaction.

The proposed publicly owned and backed subsidiary of Homes England, to facilitate new homes.

How big is the problem and what can we do to mitigate the effects?

Overheating guidance and tools for building designers

A number of cool guides to help with the heat.

The UK's Modern Industrial Strategy: A 10 year plan

Previous consultation criticism, current key elements and general support with some persisting reservations.

Building Safety Regulator reforms

New roles, new staff and a new fast track service pave the way for a single construction regulator.

Architectural Technologist CPDs and Communications

CIAT CPD… and how you can do it!

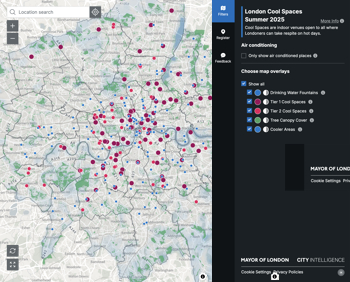

Cooling centres and cool spaces

Managing extreme heat in cities by directing the public to places for heat stress relief and water sources.

Winter gardens: A brief history and warm variations

Extending the season with glass in different forms and terms.

Restoring Great Yarmouth's Winter Gardens

Transforming one of the least sustainable constructions imaginable.

Construction Skills Mission Board launch sector drive

Newly formed government and industry collaboration set strategy for recruiting an additional 100,000 construction workers a year.

New Architects Code comes into effect in September 2025

ARB Architects Code of Conduct and Practice available with ongoing consultation regarding guidance.

Welsh Skills Body (Medr) launches ambitious plan

The new skills body brings together funding and regulation of tertiary education and research for the devolved nation.

Paul Gandy FCIOB announced as next CIOB President

Former Tilbury Douglas CEO takes helm.