Rethinking masterplanning

An introduction to Rethinking Masterplanning: Creating Quality Places

http://dx.doi.org/10.1680/prmp.60715.001

Husam AlWaer and Barbara Illsley

1.1. A chance to rethink

There has been a revival in masterplanning in recent years and this revival has occurred at a time of significant demographic and social change, widespread economic stagnation, reduced resources and enhanced concerns about the impact of climate change in many parts of the world. These conditions challenge the feasibility of applying existing masterplanning practices conceived in the past. The justification for masterplanning is no longer simply the age-old desire to create a blueprint of the future uses and appearance of a site or place; it is increasingly about seeking to improve the prospects for securing survival in the face of volatile social, economic, technological and environmental conditions. Achieving this goal is demanding, however, evidenced by the fact that contemporary masterplanning has produced relatively few new or regenerated places that are widely admired. Where success has been achieved, for example in Vancouver, Hammarby Sjo¨stad in Stockholm, Borneo Sporenburg in Amsterdam, Quartier Vauban in Freiburg, Polnoon in Glasgow and King’s Cross in London, it has been linked to the presence of sophisticated planning and urban design policies, processes and procedures as well as the use of innovative commissioning, implementation and management methods (Punter, 2003; Kasioumi, 2011; Tarbatt, 2012; White, 2015).

It is important, therefore, to ‘rethink masterplanning’, to challenge underlying assumptions, to reflect on the nature of the process and to learn from practice around the world. This book offers such an opportunity. Authors from academia and professional practice were invited to explore and discuss the many challenges facing masterplanning and set out their ideas for the way ahead. The book does not seek to present solutions to all the problems faced but it tries to unpack the issues involved, using case studies from different parts of the world to illuminate different perspectives. The intention is to capture national and international material of relevance to policymakers, built environment practitioners and academics.

Drawing on the experience of masterplanning in different contexts, including the UK, Europe, the Middle East, China and the USA, the authors provide clear evidence that new approaches are emerging, which are variously described as integrated, synergistic and adaptive masterplanning. These approaches recognise urban development as the outcome of multiple, interdependent processes involving short- and longterm decision-making across public and private sectors. Typically, they involve a process of ongoing productive visioning, collaboration, delivery, learning and reassessment which is influenced by factors such as the geographic, political and administrative context, the availability of resources and the nature of individuals and agencies involved. While legal and administrative processes will vary in different countries, such integrated masterplanning is seen to be most successful when a holistic view is taken, balancing the ambitions of stakeholders with the practical necessities of providing a framework to guide development and future growth.

1.2. Multiple views of masterplanning

Masterplanning is a complex and contested process that is understood in a number of different ways. For some, its main purpose is the production of a ‘masterplan’, a ‘spatial or physical plan which depicts on a map the state and form of an urban area at a future point in time when the plan is ‘‘realized”’ (UN-Habitat, 2009: p. 11). According to the Urban Task Force (1999), masterplans can help to focus attention on the visual impact of three-dimensional form. Recently, Falk (2011: p. 37) described the function of masterplans in the following terms: ‘Framework masterplans set out broad urban design and placemaking aspirations and principles. They allow scope for interpretation and developments within the framework’s parameters’. While, on some occasions, a masterplan is presented as providing an overarching framework, the detail of which is refined through design guidelines and design codes, on others, it is portrayed as defining the relationship between elements of the built form in some detail (Cowan, 2002; Punter, 2007; Carmona et al., 2010; Palazzo and Steiner, 2011).

Others see masterplanning as a means to an end that adjusts as the business and cultural context changes. Identifying the 1 Downloaded by [ The Institution of Civil Engineers] on [20/10/17]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. nature of anticipated outcomes is vital, however, as this gives the masterplanning process its sense of direction and purpose and also provides the basis for evaluating its success (Watson, 2009). Masterplanning as a process can play a guiding and coordinating role. It can assist in the visualisation of desired futures and assist stakeholders in moving from their initial ideas to practical solutions that can be delivered on the ground (Madanipour, 2006). Furthermore, CABE (2011) notes the potential benefit of masterplanning as a way ‘of resolving con- flicts and pursuing shared interests creatively – discussing ideas, agreeing objectives and priorities, testing proposals’.

Masterplanning can play multiple roles (Cowan, 2002; Walters, 2007; Carmona et al., 2010; Palazzo and Steiner, 2011; AlWaer and Lawlor, 2012; Bullivant, 2012; Firley and Gron, 2013; AlWaer, 2014), such as:

- offering a ‘vision’ to guide future change

- reconciling physical, economic and social issues

- establishing a blueprint for new development

- providing a spatial diagram – or PR marketing illustration

- acting as a tool for mediation among stakeholders

- creating and distributing value

- focusing on delivering place/neighbourhood outcomes g promoting community and business engagement.

So masterplanning can be seen as both a product, which sets out proposals for a specific area for land uses, movement, buildings and spaces in three dimensions, and as a process, by which organisations prepare analyses and develop strategies for development. While differences in interpretation are perhaps inevitable, it is important to recognise and analyse the complexity of masterplanning and to explore its relationship to the wider debates about the development of places.

Featured articles and news

Increased vigilance on VAT Domestic Reverse Charge

HMRC bearing down with increasing force on construction consultant says.

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

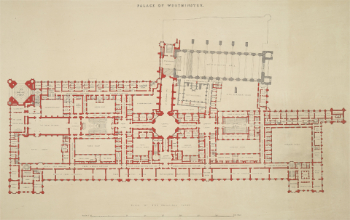

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.