Conservation as care

|

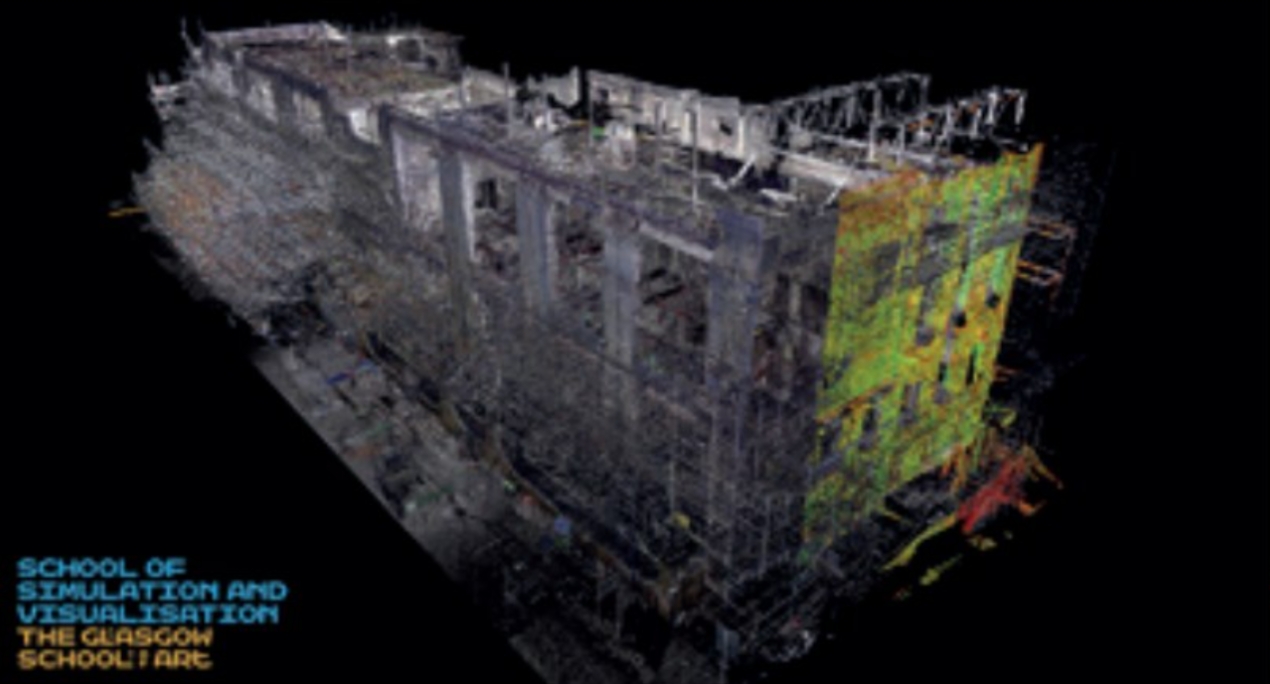

| Digital model of the burnt out shell of Glasgow School of Art following the second fire (Image: Glasgow School of Art). |

It’s the session after lunch. I’ve squeezed myself back into my chair in a full auditorium in what used to be a redundant railway building in Stirling – you may well have been there with me. It is a darkened room, and I guess we’re all a bit full, of abundant food and of all the presentations and pointers provided over the past two days. The next speaker will have to entertain the drowsy after-lunch audience on day two. I say something like, ‘engaging them might be a challenge’ to my colleague, but he responds ‘I know her. It’ll be good, she’s good. This is an important story.’ No less than 10 minutes in, I am very much proven wrong. Drone footage of the Glasgow School of Art, or of what is left of the building after the second fire, draws out gasps of horror. I pull myself out of the story to observe a mesmerised and emotional audience. This conference is on how best to restore old and knackered buildings, and the empathy is palpable. Imagine this happens to you, to your building, so helpless, incapacitated in the face of a raging fire and the destruction it leaves behind. Both the speaker and the audience full of ‘heritage people’ clearly care, a lot. For the material, the stories, and the people involved. It is like grieving a loss through a process of sharing, storytelling, restoring, and recreating. It made me realise that we hardly ever talk about restoring heritage as a practice of care – strange really, as caring for old buildings is such a common way of defining built heritage conservation.

I was attending this Heritage Trust Network event with a colleague from the Tyne and Wear Building Preservation Trust (TWBPT). I wanted to learn more about the restoration of built heritage in practice in the UK, because we had just started collaborating on a restoration project in Sunderland as part of OpenHeritage, a large EU funded research project. In OpenHeritage (see https://openheritage.eu) we research and develop ‘inclusive governance and finance models’ for adaptive heritage reuse, with a focus on economically, geographically, and/ or societally ‘marginalised’ heritage. We look at governance, community engagement, and financial mechanisms in case studies and regulatory frameworks across 15 European countries. What all these cases have in common is a group of people who care. Nothing new, you think, of course they do. Why else would you get involved in a heritage project?

Because it is so self-evident, I want to explore this idea of conservation (including restoration and heritage protection more generally) as a form of care. What are the ways we (don’t) care, the issues we (don’t) care about, the things we (don’t) care for, and who do we (not) care for? What if the ethics of care are the ethics of conservation? What is this care for, what does it do, who benefits from it? It might seem easy and innocent to think about care, and conservation, as inherently good – but are they?

In the various case studies in OpenHeritage project we explore collaborative approaches. They take different shapes everywhere, but what’s clear is that more ‘people-centred’ heritage projects are happening all across Europe. Exploring the ‘human’ dimension in heritage can mean a variety of sometimes overlapping things. Some focus on (future) use and users, other on making a wider range of stories, memories, traditions, practices, and skills integral to the process. It is visible in the ever-increasing demand for involving and engaging more people, whether that is to identify, define, (re)use, research, or restore the historic environment. It is also reflected in the changing role for heritage professionals, who are to facilitate these relations between people, and between people and heritage. This goes beyond organising engagement or skills development.

In Sunderland for example, we work on a restoration project located on a former high street in the Heritage Action Zone. The buildings saw underuse, vacancy and deterioration for decades. The current gradual restoration led by the TWBPT is undertaken in collaboration with various other local stakeholders, to develop new uses, create mutual benefit in doing the buildings up, and provide accessible space for a variety of users. It was clear from the beginning that developing a viable future for these dilapidated buildings would mean tending to their material, as much as it would be about stimulating, facilitating, and weaving a self-sustaining network of care around them, to ensure future maintenance and use. So, yes, the work includes the usual construction and restoration works. It also means that from the very beginning, we try to develop and facilitate collaborations with and between (future) tenant(s) and users, local organisations, small businesses, artists, neighbourhood organisations, the local college and university, local government and the wider heritage sector in Sunderland and the region. This network-building and collaborative work is entangled with ensuring sustained care for these buildings. This is not just fun events and creative workshops, but a long-term and often invisible process of meetings, strategising and plotting plan a, b and c, of working through conflicts, setbacks, and successes, of figuring out and formalising financial and legal responsibilities, risks, and contracts.

Some people care first and foremost for the buildings, whether that is its layers of history, bricks, or the accuracy of the restored shopfronts. Others care much more for the space that is created, and the building is valued for its ability to provide accessible space, a safe space, an event space or a community space, or a place to meet, to chat, to listen, to experience, to learn. Both care for the buildings, yet the latter are often not seen as part of the conservation process. However, aren’t heritage values, historic interest and character all part of how accessible and welcoming these spaces are? I think the answer becomes more obvious, when we ask ourselves who is – and who is not – being cared for by caring for this heritage? Who was considered in deciding which stories would be highlighted, whose needs and voices were taken into account when redesigning the space, which histories are carefully researched, and which are carelessly, or conveniently, forgotten?

It can be complicated and expensive to navigate planning, heritage, and building regulations and procedures. As a result, it may seem like one less complication to just focus on the ‘formal’ histories rather than trying to understand and include the subaltern, difficult, and unexplored ones, but is it? Many of the projects in OpenHeritage, for example the Praga Lab in Warsaw and the Jam Factory in Lviv, Ukraine focus explicitly on collecting, revealing, and showcasing invisible and forgotten stories. Stories that were not in the archives but in living and passed-on memory. Stories of residents and factory workers. For the Jam Factory, an oral history and mapping project ‘Tell Your Story’ helped build engagement and understanding. The Praga Lab team is working on a living memory exhibition to establish links between the history of manufacturing and new ways of working and making. These projects do not just spark awareness, or fill gaps in the ‘formal’ histories. They build connections and explicitly include groups of people whose heritage is often not celebrated – and thus we could argue, not cared for – informal heritage sites. Ordinary and extraordinary stories, for example of women and/or working class people and/or immigrants, as well as of the processes and practices, such as the jam making in Lviv. In Sunderland we co-organised an exhibition and events around the ‘Rebel Women of Sunderland’ project. A list of local women to celebrate was crowd-sourced via social media, and these women’s stories were brought to life through working with local creatives.

This trend of people centred heritage is great. We just need to remember who is centred – and who is cared for. Being willing to explore a more multivocal past is the start of telling a wider variety of stories. A next step is to actively find ways to address those other histories, that you may consider difficult or contested, and not just the ones that are useful to develop the project. One of the OpenHeritage cases, the Marineterrein (Navy Yard) in Amsterdam, is a relevant example here. It is considered a highly innovative project when it comes to public-private area development, with a clear focus on people. However, to highlight the character of the area, there is a focus on its central role in 17th-century shipbuilding, water-engineering, and maritime exploration, while mostly skipping over any links to the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which would mean better understanding their connections to colonisation and slavery. Also here, we can ask who is this for, who is centred? What, and who, is being cared for, by caring for this heritage in this way?

Erasure of stories can happen, however much we care. The ‘Jewish district’ of Budapest for example, saw acute gentrification and touristification as a result of the success of ‘ruin bars’ like Szimpla Kert (Simple Garden). These bars, which started to use dilapidated ‘ruins’ in the Jewish district for informal alternative, non-conformist, non-consumerist underground culture, became incredibly successful. Their ‘success’ helps maintain the physical heritage of the area and creates a stronger local night-time economy. And although Szimpla reinvests its profits in urban activism and anti-gentrification initiatives, it is not enough to counter the displacement of residents, and the rapidly changing local identity. There is also significant Jewish tourism in the district, and this easily leads to a focus on a ‘tourism’ story, whereas there is not just one story, layer, or community, and the question is how to make sure multiple voices and stories are told and heard. This is also important in terms of visual presence, including practices, events, clothing, cuisine, and gathering, and with it the restaurants, cultural institutions and commemorative spaces in the district.

As in that room in Stirling, looking at the presentation about the Glasgow School of Art, there is no doubt in my mind that the people involved in all these OpenHeritage cases care. I would even say that many of these projects would be impossible without people who care. But that doesn’t mean we should not question who they (we) care for, and who feels cared for by them (us), and what the intended and unintended results of this care work are.

What I wanted to show is that using the term care instead of conservation can help us see the importance of people-centred work, but also put it in a different light. The term draws attention to the fact that none of these restoration or conservation projects is about the buildings only. They are about relationships, whether these are between people, between people and heritage, and between people through heritage. In other words: caring for places shouldn’t be separate from caring for people, neither in the way we do projects, nor in the funding or policies. And indeed, (re)establishing and facilitating the necessary networks, trust, mutually supportive communities, and spaces is not easy, especially after long periods of neglect. The other point is that neither the work undertaken in the name of care nor that in the name of conservation, is inherently good. How you care, and who and what you care for is selective. Which people are centred in a people centred approach, who gains, and who stands to lose if care is withdrawn or imposed? Proposing this different lens, shows how conservation includes and excludes – it asks us to think about how we select who we care, who we conserve, for, and also who not, in the buildings and the stories we focus on. I hope that thinking about conservation as care can broaden our view, and shift our perspective, and enrich the way we ‘do’ conservation – as a practice of care for one another and our environment.

This article originally appeared as ‘Who cares?’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC) Yearbook 2021, published by Cathedral Communications Limited in 2021. It was written by Loes Veldpaus, a researcher at the School of Architecture Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University. She was educated an architect in the Netherlands (TU Eindhoven) and now undertakes social research in the context of heritage, urban governance, and adaptive re-use. Her current work focusses on heritage planning and policy, and the political nature of heritage, and what people think heritage is and does.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.