Working with volunteers to care for heritage

We face a drive to democratise heritage at a time when limits to professional capacity are exacerbated by austerity. Can democratising heritage and balancing budgets coexist?

This article was written by Harald Fredheim, an objects conservator, heritage site manager and archaeologist. It is based on his PhD research in the department of archaeology at the University of York.

|

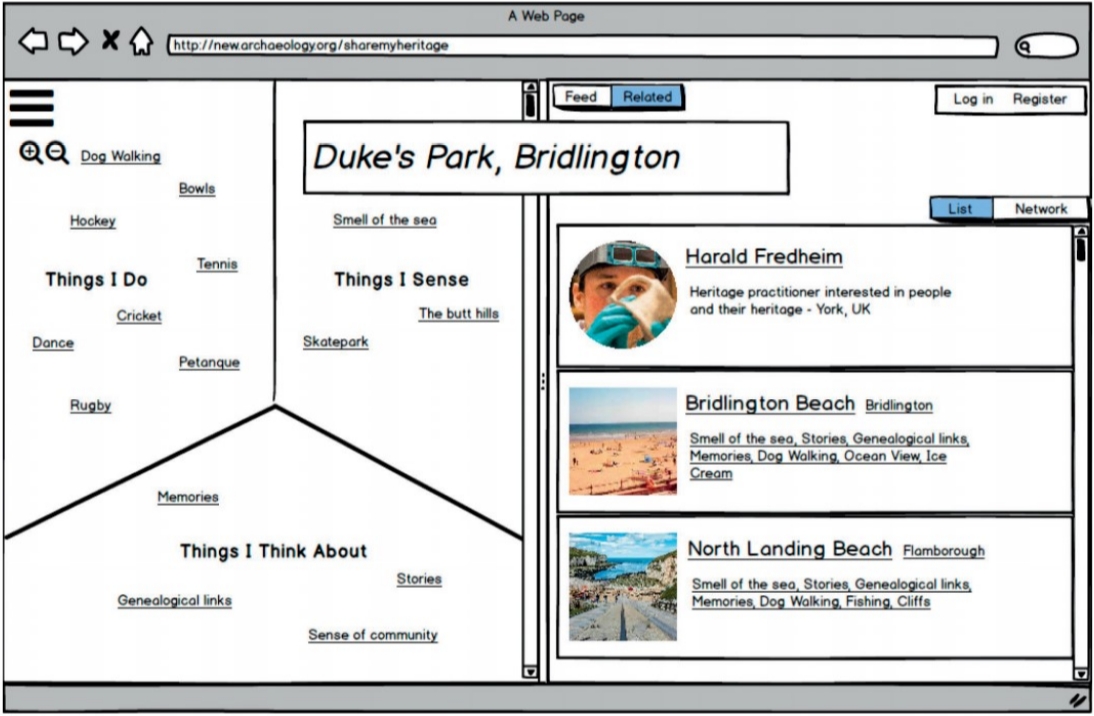

| A pilot project co-designing digital resources with three community heritage groups in Yorkshire set out to design a web-resource to share personal interpretations of local heritage. This mockup was part of a paper prototyping exercise. |

There is a concerted push in heritage scholarship and professional best practice to increase public participation in caring for heritage. This can be traced to two distinct pressures: the drive to democratise heritage and limits to professional capacity that are exacerbated during austerity. However, little attention has been paid to whether democratising heritage and balancing budgets can comfortably coexist. This lack of attention is the result of uncritically positive sentiments toward heritage and volunteering, the prevalent belief that heritage is ‘endangered’ and an oversimplified understanding of ‘democratisation’.

My research involves studying how heritage professionals work together with volunteers to care for heritage during austerity. I analyse what different ways of collaborating reveal about why collaborations were initiated, and connect this analysis to bigger questions about the future of professional labour and public participation in the heritage sector. I use a case study approach that includes both my own participatory project and established programmes in the sector.

What I am finding is that how we conceptualise heritage drives perceptions of legitimate expertise that in turn dictate how roles and responsibilities are divided when professionals and volunteers collaborate. This leads me to worry that unless we are willing to change our ideas about what heritage is and what it means to care for it, initiatives to increase public participation will result in devaluing professional labour and exploiting volunteers.

I begin by questioning the idea that participating in heritage is necessarily beneficial. While research into how participation can benefit participants is important, reports that set out to demonstrate that (rather than whether, when, for whom or in which ways) heritage volunteering is beneficial to participants do us a disservice. They keep us from critically reflecting on how we work with volunteers and condition us to celebrate increased public involvement as a victory of ‘democratising’ the sector, even where this is the result of unpaid volunteers doing work that was previously performed by displaced professional colleagues.

This idea of democratisation is significant, because there is a widespread perception that Laurajane Smith’s now infamous ‘authorised heritage discourse’, which identifies heritage as elitist and exclusive, must be countered by democratising heritage, through more inclusive ways of working.

I draw on a wide range of social science scholarship to understand how increasing public participation does not necessarily involve democratisation in the way it is usually understood. Ricardo Blaug has suggested that there are two different kinds of democratisation: incumbent and critical. While incumbent democratisation involves increasing participation within established processes, reinforcing the legitimacy of institutions, critical democracy denotes unsanctioned forms of participation that challenge existing power structures. The idea of incumbent democracy highlights that power can be retained through increasing participation by controlling the forms participation takes – and that this control may be exerted unintentionally.

It is a slippery distinction, but one I experienced first hand when I realised that, despite my critical intentions, my own participatory project had ended up being about changing my partner groups to work in the ways I thought they should, instead of helping them meet their own goals. I wanted to share power over decision-making within the partnership, but the way I designed the project undermined realising this ideal in practice. Our initial interactions reinforced preconceived notions about expertise and kept us from identifying that the project was not providing what my partners wanted until it had become difficult to change it.

Critical perspectives on participation are not unique to democratic theory. Sherry Arnstein’s often cited ‘ladder of participation’, from the early days of the participatory planning movement in North America, identified that while participation can be empowering, it can just as readily be tokenistic and manipulative. This danger has also been identified by researchers in development studies, exemplified by the edited volume ‘Participation: the new tyranny?’ One of the chapters critiques the idea of empowerment, shifting the focus from ‘how much’ to ‘what’ participants are empowered to do. Like Blaug’s incumbent democracy, it identifies the danger that we, as professionals, decide others must be empowered and impose our ideas of what they should become, thereby denying participants agency over their own empowerment.

|

Arnstein’s Ladder (1969) Degrees of Citizen Participation |

In her contribution to a recent volume on ‘The Ethics of Cultural Heritage’, Emma Waterton articulates the need for professionals involved in community engagement practices ‘to think seriously about the risks of becoming exploitative’ (2015). In a UK context, where social scientists are identifying the inevitability of volunteers being manoeuvred to replace aspects of professional public service provision during austerity, and the Museums Association has reported observing this shift in its annual Museums Survey, the risk of exploiting volunteers must not be downplayed.

The geographer Marit Rosol, who has studied public participation in managing urban green spaces in Berlin, highlights that the ‘outsourcing of traditional state functions to civil society organisations’ does not necessarily involve increasing citizens’ participatory rights (Rosol, 2016). She goes on to note that locals resent ‘their prescribed role as stop-gap’ and are not prepared to deliver previously professional services without pay.

Acclaimed author Naomi Klein has coined the term ‘changeless change’: ‘the kind of innovation that simultaneously upends current practices and studiously protects existing wealth and power inequalities’ (Olma, 2016). In my research, I use this idea of changeless change to ask what participatory heritage initiatives actually change. This question is especially significant in a society that is increasingly enamoured by innovation. What I am finding in my research is that increasing public participation does not contribute to democratising heritage in a critical sense unless it moves beyond working in new ways to include sharing power over, not merely within, participatory projects. This must involve changing how we think about heritage and define legitimate heritage expertise. Divorced from such reconceptualisation, participatory initiatives are prone to devalue professional labour and exploit volunteers by asking participants to work without pay.

Established definitions of heritage and conservation entrench the idea that voluntary efforts are inherently inferior to those of professionals and that volunteers require professionals to facilitate upskilling, empowering and capacity building. It is in this context that Caitlin DeSilvey’s recent book, ‘Curated Decay’, is especially significant for participatory heritage practice. Through concepts like ‘palliative curation’, which actively reject the idea that heritage is endangered, DeSilvey attempts to legitimise a range of alternative ways of caring for heritage that move understandings of heritage away from tangible remains and conservation beyond arresting physical change. In doing so, she alludes to how different definitions of heritage can create new participatory dynamics, in which volunteers need not be cast as less capable or a necessary stop-gap.

Most participatory heritage projects that facilitate public participation in caring for heritage do not propose new definitions of heritage, nor promote alternative ways of caring for heritage. It may not seem necessary to do so in order to avoid inadvertently exploiting volunteers and devaluing professional labour. Yet there is a real danger in simultaneously perceiving volunteers as a resource and assuming that participating benefits volunteers. It promotes volunteering as an enigma, through which everyone always benefits.

This is the underlying logic behind rationalising crowdsourcing projects in the heritage sector, whereby volunteers perform unpaid work remotely through digital interfaces. Despite alarming drop-out rates, it has led to the established practice of prioritising the development of volunteer recruitment and retention mechanisms, such as automated reminder messages, at the expense of attempting to improve the volunteer experience. In one widely celebrated case, the organisers identified volunteers having a good time as an intended outcome. Yet, despite low participation rates for their target demographic and many volunteers leaving the project, it seems they never stopped to ask whether they were actually providing an enjoyable experience.

It is crucial that we continuously re-evaluate the design of our participatory projects. Are they deliberately designed to benefit participants, and how are these benefits constrained by other project drivers? I have attempted to present some of the theoretical lenses I use for this analysis in my research through this short article. Together, they highlight that democratising heritage in a critical sense must not only involve increasing participation within existing structures, but also opening up established concepts and practices for debate.

I would like to challenge all of us who work with volunteers to think seriously about the risks of becoming exploitative. This must involve both designing participatory projects to benefit volunteers, and to consider how our projects contribute to broader divisions of volunteer and professional roles and responsibilities in caring for heritage during austerity. It begins by recognising that volunteering is not an enigma that inevitably provides both free labour and benefits for all. Only then can we move beyond manoeuvring volunteering to fill gaps in professional work-flows to thinking creatively about heritage and how we can best care for it together.

References

- Arnstein, S (1969) ‘A ladder of citizen participation’, Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4)

- Blaug, R (2002) ‘Engineering democracy’, Political Studies 50 (1)

- DeSilvey, C (2017) Curated Decay: heritage beyond saving, University of Minnesota Press

- Fredheim, H (2018) ‘Endangerment-driven heritage volunteering: democratisation or “changeless change”’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24:6

- Henkel, H and Stirrat, R (2001) ‘Participation as spiritual duty: empowerment as secular subjection’ in B Cooke and U Kothari (eds), Participation: the new tyranny? Zed Books

- Olma, S (2016) In Defence of Serendipity: for a radical politics of innovation, Repeater

- Rosol, M (2016) ‘Community volunteering and the neo-liberal production of urban green space’ in Y Beebeejaun (ed), The Participatory City, Jovis

- Smith, L (2006) Uses of Heritage, Routledge

- Waterton, E (2015) ‘Heritage and community engagement’ in T Ireland and J Schofield (eds) The Ethics of Cultural Heritage, Springer

This article originally appeared as ‘Why do you work with volunteers?’ in IHBC’s Context 155, published in July 2018. It was written by Harald Fredheim, an objects conservator, heritage site manager and archaeologist. It is based on his PhD research in the department of archaeology at the University of York.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

HE’s Research Magazine publishes a major study of the heritage of England’s suburbs

The article traces the long evolution of an internal programme to research 200 years of suburban growth

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.