Heritage and mental health

|

|

Burgh Castle Almanac Summer Solstice walk at Burgh Castle Roman Fort in June 2022. Part of the Water Mills and Marshes project led by the Broads Authority (NHLF funded), Burgh Castle Almanac is now a community group set up by members, contributing to the heritage linkworker pilot in Great Yarmouth and Waveney, funded by Historic England. (Photo: Emily Cannell) Inset: These walks are advertised to local people using social prescribing and NHS mental-health services. (Photo: Robert Fairclough). |

People on low incomes, including many living with mental-health problems, are least likely to visit historic sites, but gain more wellbeing benefit than others when they do.

| ‘We had to be delicate with the stuff because you have to wear the gloves and everything. So in case they, like, fall apart… it was really interesting how careful you have to be. You have to treat these things like you would treat a human being basically’ (participant, Conservation for Wellbeing). [1] |

There is a chasm between what people living with mental-health challenges need and what is on offer. With 1.4 million people on NHS mental health waiting lists and collapsing staff recruitment and retention, services are unlikely to stabilise before 2024. Patients risk being dehumanised as compassion is eroded by pressure. Social prescribing, the use of non-clinical interventions, is accelerating, but link workers and voluntary agencies are overstretched.

The future looks bleaker when inequality is taken into account. Poverty, deprivation, unemployment, poor housing and exclusion are major risk factors for mental-health problems, and the cost-of-living crisis will make things worse. In these circumstances, the case for using every community asset for mental wellness is compelling.

The UK has heritage aplenty: 99 per cent of people in England live less than a mile from a listed asset. And people like it: The Repair Shop on BBC 1 had 6.7 million viewers in 2020. Responding to this interest by refocusing early intervention and prevention away from institutions overcomes systemic exclusion and helps people through mental illness’s bleak landscape.

We meet participants in our heritage and mental-health projects through partnerships with inclusion support organisations like the Richmond Fellowship, or DIAL in Great Yarmouth. Their users are unlikely to visit historic places with an entry price of £14 (National Trust adult ticket) when basic Universal Credit is around £81 a week. People on low incomes are least likely to visit historic sites, but gain more wellbeing benefit than others when they do. The correlation between deprivation and mental illness suggests that many people living with mental health problems do not benefit as they could from heritage.

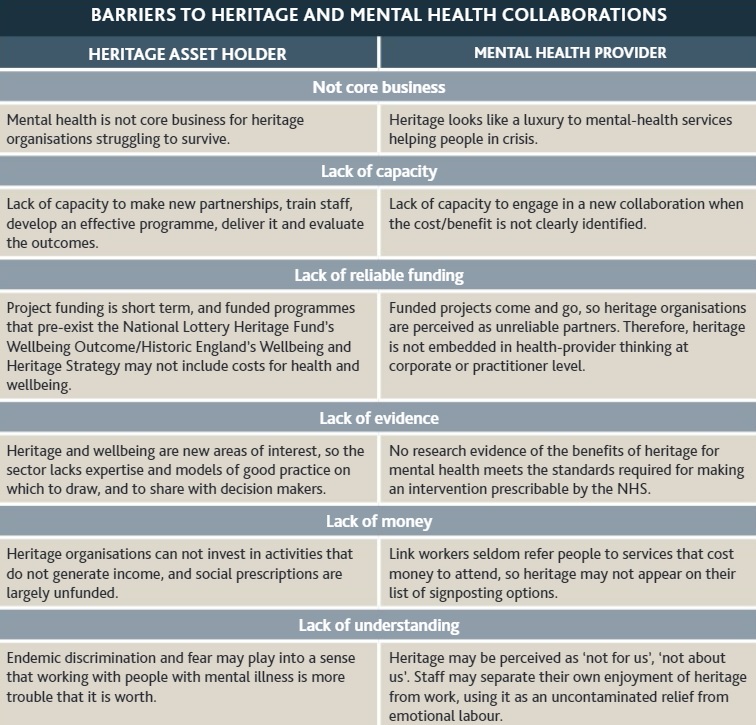

There appears to be something distinctive in the interplay between heritage and creativity. We theorise that expanding imaginative, physical, intellectual and temporal space through high-quality engagement with historic places and objects relieves the constriction of mental illness. As an ex-conservator, I am interested in the damage/repair analogy that emerges in conservation-based projects. However, benefits identified by heritage and wellbeing research largely overlap with those of green or creative activities by delivering on the New Economic Foundation’s five ways to wellbeing (connect, be active, be curious, keep learning and give), so heritage’s availability matters more than its particular characteristics. The barriers for heritage organisations wanting to work with people with mental-health challenges are high, and vice versa. It is our job to overcome them.

We convene partnerships of participants, heritage organisations, mental-health providers and universities to create pilot projects and scale up the ones that work. Projects in ancient landscapes such as the Stonehenge and Avebury world heritage site (Human Henge), or at Burgh Castle Roman Fort (Burgh Castle Almanac), are co-produced, small-group experiences of at least 10 sessions where people explore a heritage asset and reflect on it creatively. As well as the historic environment, we work with archives, conservation and museums, and our Heritage Linkworker pilot in Great Yarmouth and Waveney is testing how people referred through social prescribing can enjoy local history. Our four-session consultancy offer helps organisations which want to set up their own projects.

We encourage people to participate in everything we do by joining our expert advisory board and becoming trustees, working as volunteers and staff, and attending successor groups. Evidence is that our projects improve people’s mental health, including in the longer term, and that every £1 we invest returns £12 of social value.

Because we want to change the world, we gather high-quality evidence of outcomes, present to conferences, publish books and articles, use social media, join networks and bang the drum for radical inclusion in heritage. The key strategic friend for this cross-sectoral work is the Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance, and we have been well supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Historic England and the Heritage Alliance. Case studies of best practice in this field can be found in our report for the Baring Foundation published in November 2021, Creatively Minded and Heritage. [2]

I leave you with the words of a participant in Burgh Castle Almanac, from the evaluation by Willis Newson. [3]

|

Stuart’s story Burgh Castle Almanac helped Stuart overcome a traumatic early life, an abusive childhood, substance abuse and mental-health problems. In BCA he has found belonging in a safe and welcoming space, enabling him to build a new family of friends. It has rekindled a love of nature, heritage and learning, giving him a sense of purpose. Unable to hold it together I’ve always used work to manage things, keep things at bay. I managed to keep it together like this until I just couldn’t do it anymore. I put on this persona during the day and as soon as I got home my mood would hit the floor. I just couldn’t do the falseness and faking anymore. Eventually I had a proper breakdown. I tried to take my life again. I was really in a bad way. I was back into hospital. I’ve been with the mental health recovery team since 2018. This was the year that one of the support workers introduced me to Burgh Castle Almanac. My wife said I should give it a try. I had become very insular and didn’t want to go out or do anything. Even with her and the support worker behind me, I still wasn’t sure about it. But they really pushed me and I’m so grateful that they did. That first time I went along, I felt fear: fear of the unknown; fear of being with a group of people I didn’t know; fear of not being accepted. Absolute pure fear! When I met [the facilitator], I felt at instantly home. Her openness and her welcoming manner put me at ease straight away. And everyone else was so welcoming too. It was like being in a family, a loving family. And that was something I’ve never had. Learning new skills, rekindling old ones Burgh Castle Almanac ticked all the boxes for me: I love the outdoors; I love nature; I love history. Doing all those things together was spot on. And through everything we’ve done together at Burgh Castle, I’ve got back into my creative side as well. I’ve done creative writing, I’ve written songs. I’ve learned so many different things. I’m reading books, I’m researching things on the internet, which I would never have done before: the history of Burgh Castle, the history of the Roman army and the Iceni tribe, and Boadicea. There’s just so much to immerse yourself in. When you’ve got some knowledge of something, you enjoy it more. On the last walk I led, people were firing questions at me left, right and centre. I can tell them the answers because I’ve found it all out and researched it and, yeah, I’ve become an expert. |

References:

- [1] Rubinstein, Diary (2021) Conservation for Wellbeing Project Research Report, Restoration Trust

- [2] Restoration Trust (2021) Creatively Minded and Heritage, Baring Foundation

- [3] Willis, Jane (2021) Burgh Castle Almanac Evaluation, Restoration Trust and the Broads Authority

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 173, published in September 2022. It was written by Laura Drysdale, director of the Restoration Trust, an award-winning charity that involves people living with mental health challenges with heritage and creativity. www.restorationtrust.org.uk.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Diversity.

- Empowering the construction industry to take action on mental health.

- Equity, diversity and inclusion in the heritage sector.

- Ethics.

- Heritage asset.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Mental health and wellbeing.

- Mental health in the construction industry.

- Tackling mental health - 6 point plan.

- Tackling mental health issues in construction.

- The statistics behind mental health within construction.

- World Mental Health Day.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.