The design of temporary structures and wind adjacent to tall buildings

This article was originally published by Structural-Safety in December 2015. Structural-Safety combines the activities of CROSS (Confidential Reporting on Structural Safety) and SCOSS (Standing Committee on Structural Safety). The advice of the Building Research Establishment and the UK Wind Engineering Society is gratefully acknowledged.

Wind Adjacent to Tall Buildings subsequently appeared in the Spring 2016 Edition of CIAT’s AT magazine.

This article is aimed at those who design or commission temporary structures that are subject to wind loading and adjacent to tall buildings. Such temporary structures may be particularly prone to adverse wind effects by virtue of their relative position.

Reports to CROSS have raised concerns about the design of temporary works to resist wind loading in urban environments. Temporary works have suffered local wind damage, and it is suspected that is, in part, because wind loads have not been determined correctly. Although reports relate to urban environments, temporary structures adjacent to tall buildings in exposed locations may also be adversely affected.

The current UK Code of Practice for wind actions (BS EN 1991-1-4) addresses wind loading on buildings but only gives limited guidance on the effect of wind flow on nearby structures. Guidance on a small number of scenarios is given in the UK National Annex to BS EN 1991-1-4 (with further background information in PD 6688-1-4). Clause NA.2.27 addresses a particular case of funnelling (where flow is forced into a smaller volume and so is accelerated).

An enhancement in pressure coefficients is given where the walls of two buildings face each other and the gap between them is less than a given value. Designers should always be mindful of the potential for funnelling, where air is forced into a narrow gap. The increase in wind velocity will increase the dynamic pressure and raise pressures on the surfaces of the gap.

The flow around buildings is complex and three-dimensional. However, it is possible to understand some of the underlying principles to assist in deciding when specialist advice is required. A desk study by a specialist can often provide a good indication of the significant issues.

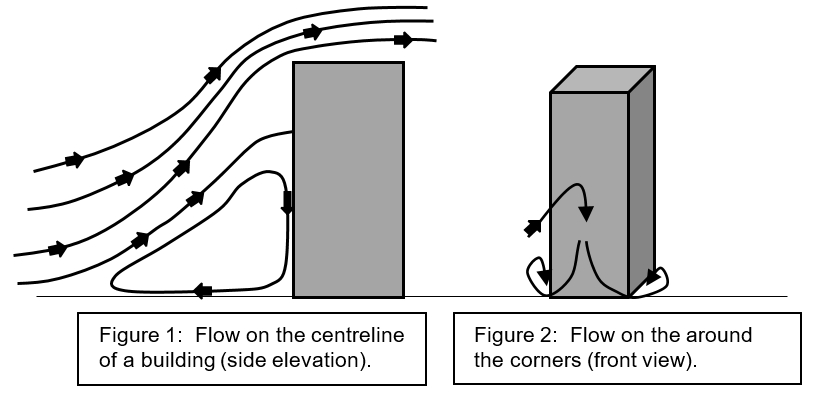

Consider a rectangular building normal to the wind direction. The building obstructs the free flow of air, creating positive pressure on the windward face. This air flows down the face of the building due to the variation of oncoming wind speed (and pressure) with height. In effect it acts like a scoop, collecting air from higher levels and delivering this to ground level. This is commonly referred to as a downdraft.

The winds brought down to ground on the centreline of the building re-circulate, counter-intuitively reversing the direction of the wind near ground level. Winds brought down to ground away from the centreline of the building accelerate around the upwind corners of the building; the down-drafted air is drawn to the negative pressure in the wake of the building. If a structure (temporary or permanent) is located directly in front of a building, in the corner zones or in the separated flow region downstream from the corners, it is possible that it will experience wind pressures far in excess of those for which it was designed (if considered in isolation to its surroundings). This effect is illustrated below.

Some design guidance is given in reference [4] on surface winds near isolated high-rise buildings, based on the work of Maruta [5]. This is a purely empirical method so is only valid over the range of parameters to which the model was fitted. A method is also given in Annex A.4 of BS EN 1991-1-4, and provides a first approximation for the peak velocity pressure on structures surrounding a single tall building. However, many urban environments are far more complex, with many adjacent tall structures.

A conservative approach is to use the height of the tallest building as the reference height to calculate the dynamic wind pressure used near ground level. To indicate the significance of the effect, the wind pressure at ground level could be more than doubled by the blockage effects of an 80 m tall building (note 1).

Guidance is given in BS EN 1991-1-4 and the UK National Annex on the high local pressures that arise on the edges of walls and roofs. Designers should recognise that wind loading is transient, cyclic and likely to be turbulent. Therefore, connections (e.g. for cladding, sign boards, fencing, etc.) in these zones should be sufficiently robust to resist fatigue.

Careful consideration should be given to the selection of probability and seasonal factors when determining wind loads in accordance with EN1991-1-4. Recommendations on return periods depending on the duration of the works are given in EN1991-1-6. Particular care should be taken before adopting seasonal factors, as this requires strict control and certainty over the period of installation of the temporary structure.

Designers of temporary structures should consider how the environment around a temporary structure will change during the construction process. Different stages in the construction of a tall building may introduce blockage effects that alter or funnel wind flow, and give the critical design case for wind loading (e.g. with the addition of cladding). Advice should be sought in critical and complex situations, where a competent wind engineer may be able to help identify the main wind-related issues or suggest quantitative studies (e.g. wind tunnel or otherwise) where necessary.

Although this article was prompted by concerns regarding the design of temporary structures around tall buildings, it should be noted that wind around tall buildings can lead to unpleasant (and sometimes dangerous) conditions for pedestrians. Information to assist designers, planners, developers and building control officers in dealing with the wind environment around buildings is given in BRE Digest 520. The contents of this digest are also relevant to the design of temporary structures around tall buildings.

Note 1: This example is indicative only. Designers should determine the appropriate wind pressure for the particular site under consideration, either using the conservative approach suggested, or by more detailed methods of assessment.

--CIAT

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- CIAT.

- Collaborative Reporting for Safer Structures UK.

- Computational fluid dynamics.

- Computational fluid dynamics in building design: An introduction FB 69.

- Lateral loads.

- Racking.

- Shear force.

- Structural principles.

- Taipei 101.

- Temporary building.

- Temporary works.

- Types of structural load.

- Uplift force.

- Vibrations.

- Wind load.

[edit] External references

- (1) BS EN 1991-1-4: 2005. Eurocode 1 – Actions on structures. Part 1-4: General actions – Wind actions (Incorporating corrigenda July 2009 and January 2010).

- (2) UK National Annex to Eurocode 1 – Actions on structures. Part 1-4: General actions – Wind actions (+AMD A1: 2010).

- (3) PD 6688-1-4: 2009: Published Document. Background information to the National Annex to BS EN 1991-1-4 and additional guidance.

- (4) Cook, N.J. The designer's guide to wind loading of building structures. Part 2. Static Structures.

- (5) Maruta, E. The study of high winds regions around tall buildings. PhD thesis. Tokyo, Nihon University, 1984.

- (6) Blackmore, P. Wind microclimate around buildings. Building Research Digest (BRE) 520, 2011.

- (7) BS EN 1991-1-6: 2005. Eurocode 1 – Actions on Structures. Part 1-6: General actions – Actions during execution.

Featured articles and news

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help the homebuilding sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.

Demonstrating that apprenticeships work for business, people and Scotland’s economy.

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.

Comments

This is an interesting article on the effect of tall buildings on the wind load at ground level. It discusses the impact if a temporary structure/low building is placed close to the tall building. It does not address the issue if a tall building is to be built in a predominantly low rise building area. In this case, the wind pressure on the nearby low rise buildings could be nearly doubled. This increased wind load would not have been considered in the original designs.

Consequently, one potentially very challenging question will be raised: if a tall building is to be built in a predominantly low rise building area, all buildings in the influencing zone could be subject to increased wind load. Should all existing buildings be checked against this increased wind load? Should the owners of the buildings in the influencing zone be notified about the increased wind load?

Clearly this is not something that the engineers can address alone. A wide range discussion with client, legal team, designers, contractors will be required.