Richard Norman Shaw and the construction of Albert Hall Mansions

This article originally appeared in Context 145, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in July 2016. It was written by Paul Latham.

Combining picturesque romance with orderliness, the architect Richard Norman Shaw helped to open the door to social acceptance of the new practice of flat-dwelling in London.

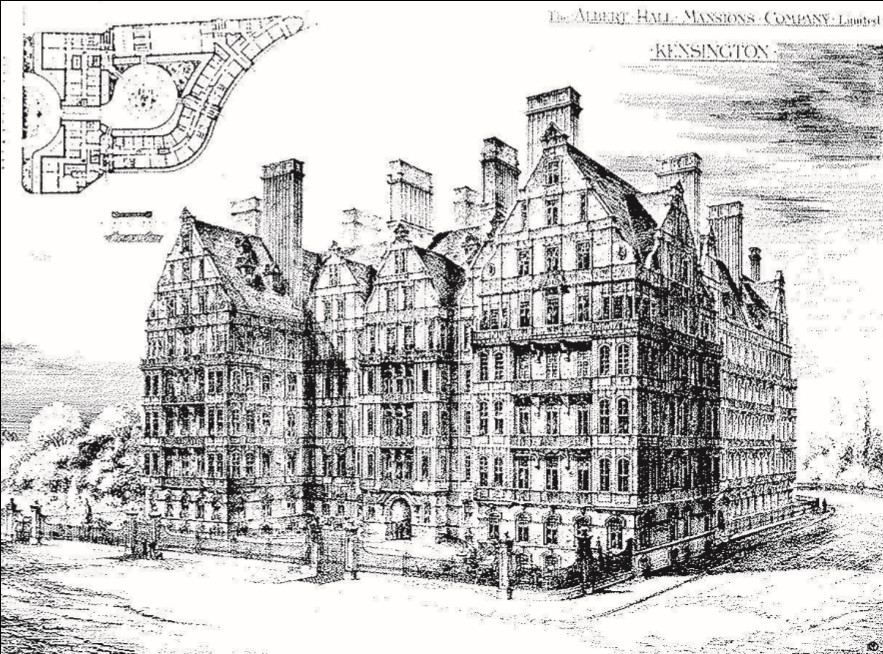

[Image: Albert Hall Mansions as planned by Driver and Rew on the Hankey system, elevated by Richard Norman Shaw, 1877

Before the 1870s, blocks of flats were almost exclusively built by the housing reform societies such as the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company and Peabody Trust, whose model Peabody Square was built in 1865. The first London apartments for the aspiring upper middle classes were built to Italianate designs of Henry Ashton in Victoria Street between 1852–4. There were only a handful of similar developments in the following 30 years due to a deep rooted English prejudice against apartment living which, according to the Builder in 1879, was considered to be ‘the Parisian mode of life’ – with the implicit alien, cosmopolitan overtones implied. This prejudice began to break down as developers realised there was demand for the convenience of a pied-à-terre in town from a wealthy, socially mobile section of society, where the cost of servants could be shared by the landlord’s provision of communal servicing.

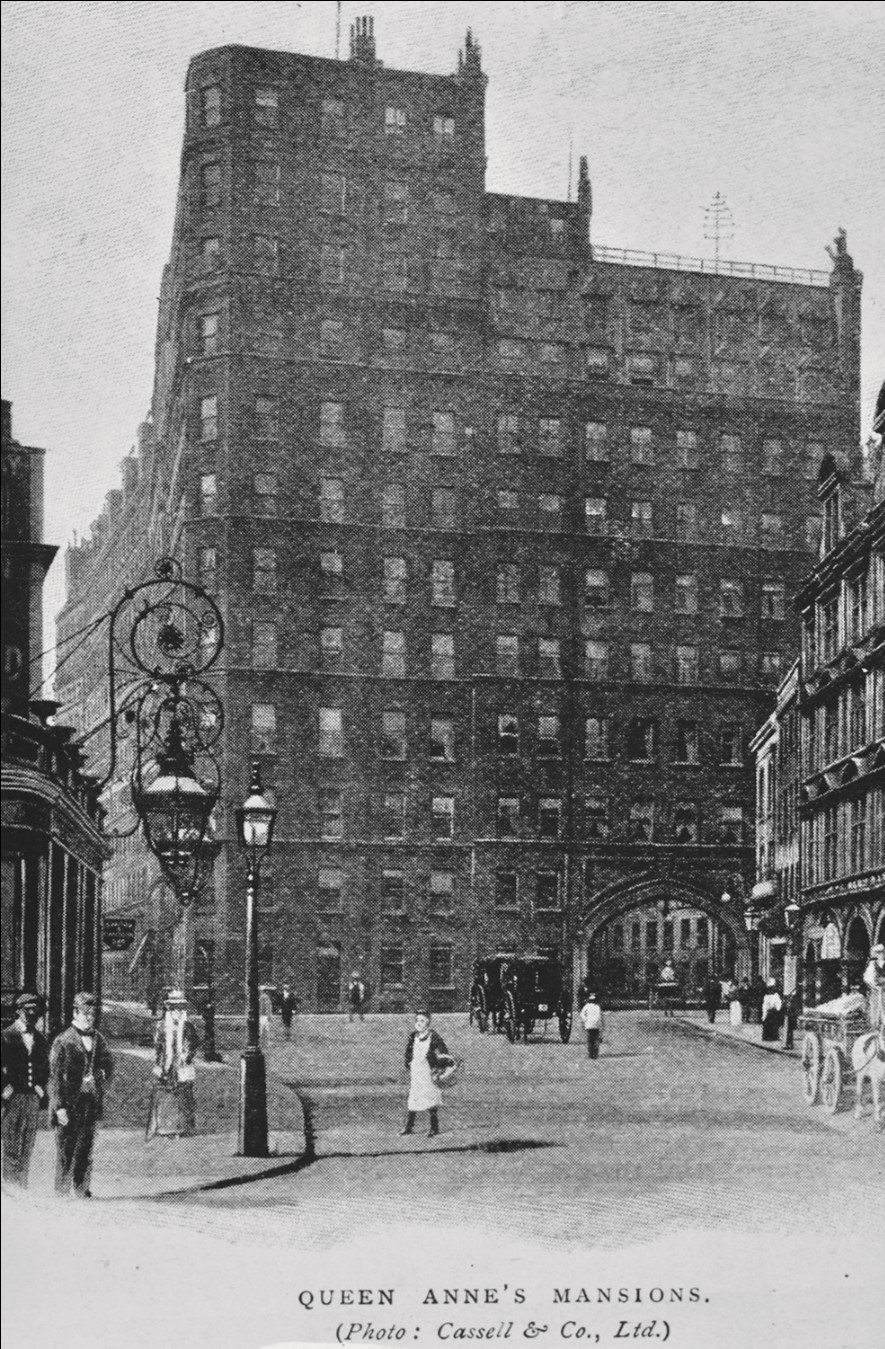

London’s first major speculation to meet this demand was Queen Anne’s Mansions (1873–90), built between Victoria Street and St James Park by the wealthy merchant banker and speculator Henry Hankey. The ‘Hankey system’, as it became known, was based upon the idea of cooperative living, the absence of private kitchens and landlord’s provision of servants, communal dining and recreation facilities. Queen Anne’s Mansions was marketed more like an apartment hotel, ‘not 10 minutes from all the clubs, combining the advantages of a private house, the freedom of a hotel, and the luxury of a club’.

[Image: Queen Anne’s Mansions, c1898 (LCC Photographic Library, LMA Record 167794)]

This scheme was initially an undoubted commercial success, but Hankey’s mansions were openly regarded as an architectural abhorrence, reinforcing the established middle-class prejudice against flat living. James Knowles, architect of the Grosvenor Hotel in Victoria Street, complained the Mansions constituted ‘an eyesore so offensive as would disgrace the whole neighbourhood of Westminster, overshadowing all its splendid and historic buildings, and turn this quarter of London into a laughing stock’. The Times described the mansion block as ‘the most elevated thing in bricks and mortar since the Tower of Babel.’ Hankey was also in bitter dispute with the Metropolitan Board of Works over fire safety due to the height of an extension proposed to his building. It took the architectural skills of Richard Norman Shaw, the patronage of the Commissioners of the Great Exhibition and the construction of Albert Hall Mansions to alter the negative perception of flat-living created by Hankey.

While the 1851 exhibition was an international success, both in promoting the arts and technology, and commercially, subsequent international exhibitions organised in 1862, 1869, 1871, 1873 and 1874 ran into increasing financial difficulty. By 1874, the commissioners were embarrassed to hold mortgage debt of £208,500 with an annual income of only £8,744.

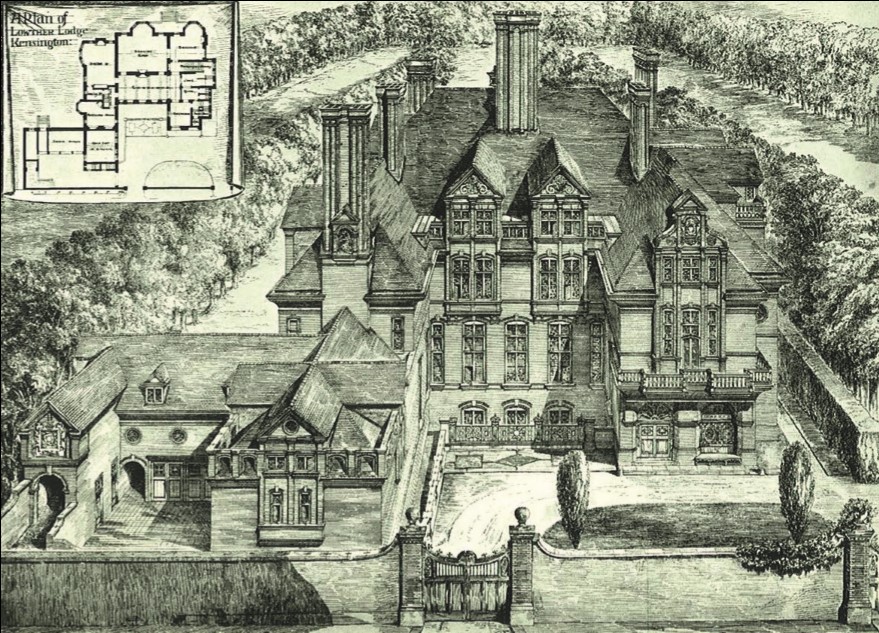

In March 1875, at the time of the completion of the first 10-storey stage of Queen Anne’s Mansions, Sir Henry Hunt, the commissioners’ surveyor, invited tenders for the lease of a valuable site fronting Kensington Road and Hyde Park to the north, and the new Albert Hall to the east. By December, a tender had been accepted from Thomas Hussey, builder, of Kensington High Street, for a 99-year building lease. In April 1876 Hussey’s architects presented plans for a row of large houses on the site. The commissioners, sensitive to the need to maintain the high quality of development established by Shaw in the recently completed Lowther Lodge (1873) and 196 Queens Gate (1875), were unhappy with the architecture and rejected the designs. Hussey was persuaded to appoint Shaw to redesign Hussey’s elevations at the commissioners’ expense.

[Image: Lowther Lodge, 1873. The site of Albert Hall Mansions is in the background.]

Shaw’s reworked houses were never to see the light of day. In large part this was because of the initial success of Queen Anne’s Mansions. Henry Hunt had from the beginning been in favour of ‘a large pile of buildings to be used for Residential Chambers’. Hussey went back to his original architects Driver and Rew to design a mansion block of flats exceeding 100 feet in height.

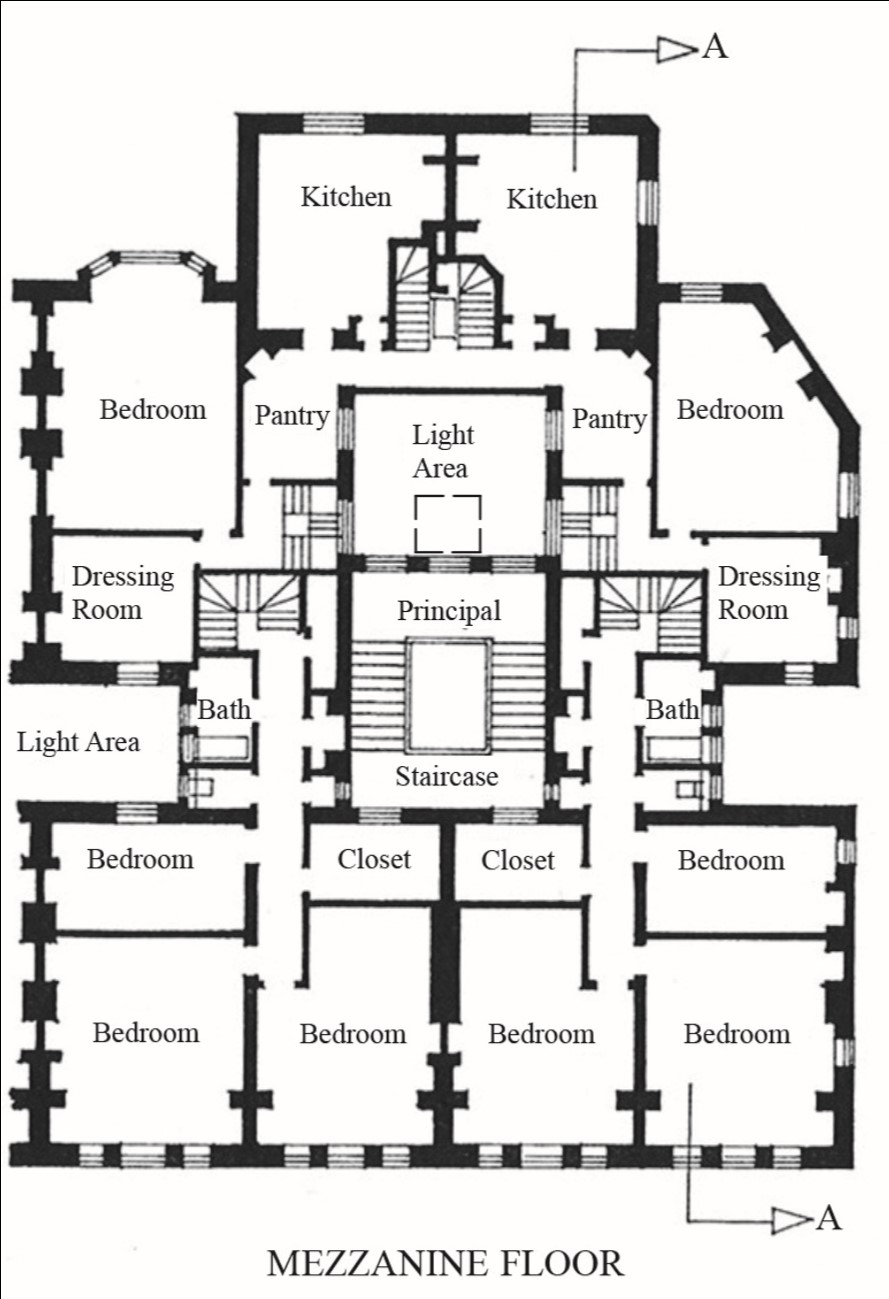

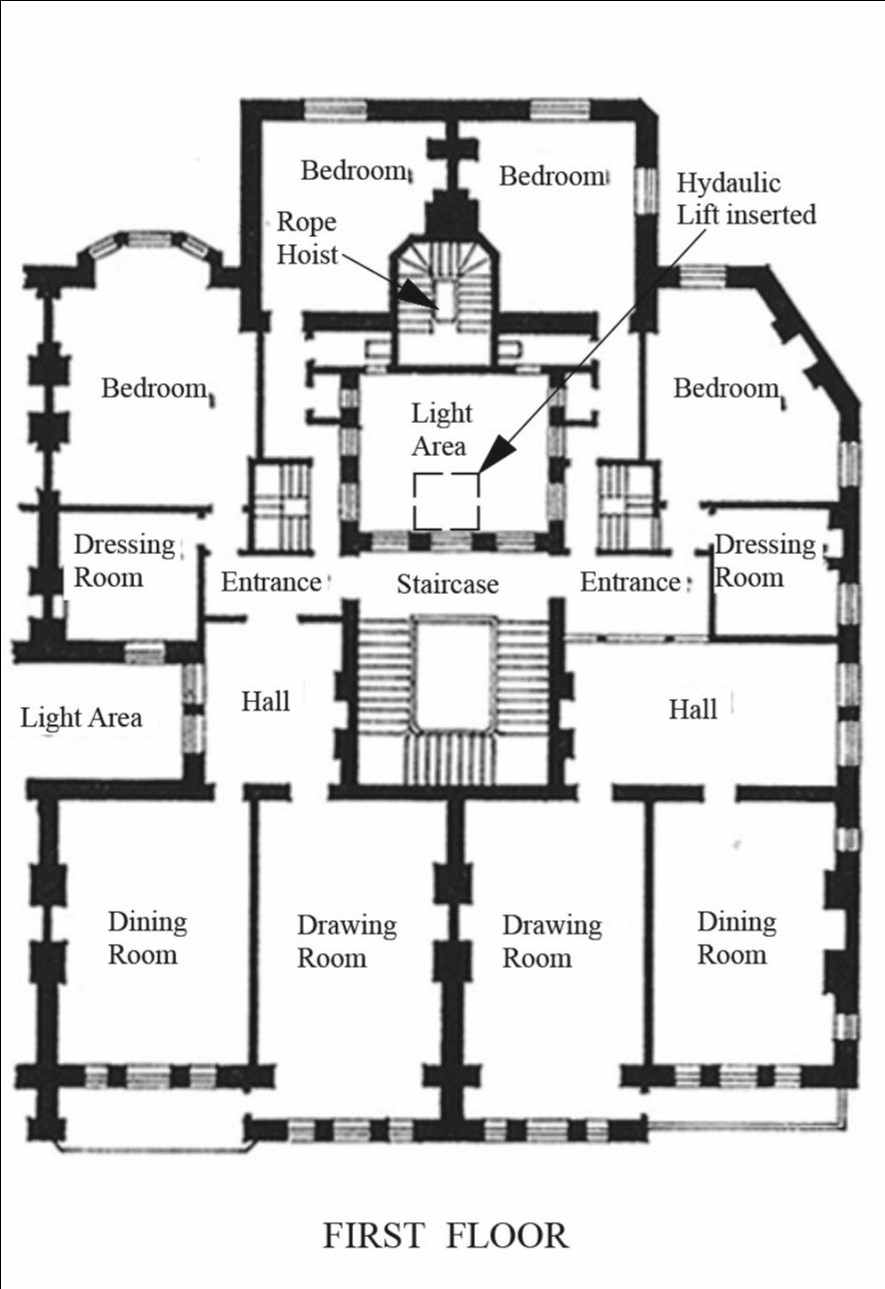

With a weakening in the market for Hankey’s flats due in large part to the public controversy over their height and appearance, the commissioners objected to Driver and Rew’s flats proposal on the Hankey system, purportedly on grounds of fire safety due to its height. They employed Shaw to collaborate with Driver and Rew, Shaw essentially elevating their proposals. The result was described by a clearly unconvinced Shaw in 1877 as a design he was ‘quite prepared to father’. The commissioners, equally unconvinced by the resulting design, decided to present a fait accompli to Hussey, appointing Shaw to design a row of houses from scratch. The proposition was rejected by Hussey, who bowed to the inevitable by appointing Shaw to take over the entire flats project as architect.

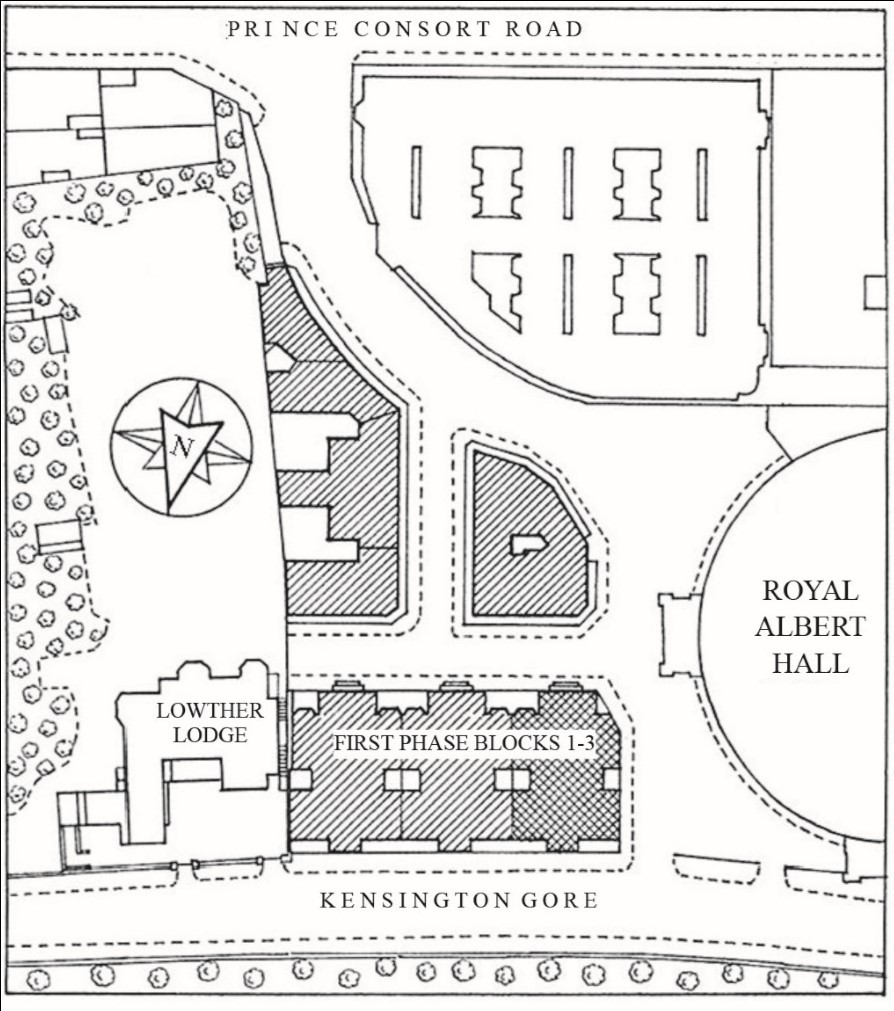

Shaw promptly visited Paris with his assistant Ernest Newton to research the planning of continental flats. The development was to be started on the Kensington Gore frontage only and would be divided into three identical blocks, each with its own staircase and entrance. This would enable phased construction as the demand from purchasers was established. All communal facilities incorporated under Hankey’s system were abolished, except provision of a porter’s and servants’ rooms in the basement. Seen from the park, the scale, completely overwhelming the adjoining Lowther Lodge, is articulated by three giant Dutch gables atop projecting bays linked by horizontal balconies, emphasised by a two-storey mansarded attic.

[Image: Site plan, Albert Hall Mansions]

|

|

|

[Image: Plans and a section of Albert Hall Mansions, 1879]

To focus on wealthy families, Shaw planned 15-feet-tall reception and dining rooms overlooking the park, with a split-level arrangement at the rear accommodating three bedrooms, a kitchen and pantry. Bachelors were accommodated in a two-storey attic accessed by a top-lit central stairway discharging at ground level into a grand public lobby in the Parisian tradition.

The first phase three blocks of Albert Hall Mansions facing Hyde Park was planned without passenger lifts, necessitating a climb by staircase for the bachelors of up to seven storeys. However, by 1884 the London Hydraulic Power Company had completed the first public high-pressure water-power distribution system, extending to Kensington in the west. The American Elevator Company retrospectively installed hydraulic passenger lifts in the completed blocks and subsequent phases the same year.

Shaw’s design incorporated a back staircase accessed from a separate service entrance to the apartments architecturally paired with the main entrance. A rope-and-pulley lift to transport coals to the upper floors from basement under-pavement cellars was located within the service stairwell. The basement was dedicated entirely to service accommodation, housing a porter’s living room towards the front, 11 ‘spare rooms’ and a kitchen, presumably housing the small army of servants required to transport coals to set the numerous fires. Six trunk cellars, one allocated to each of the split-level apartments, were housed in the basement. Trap doors within the service entrance lobby enabled trunks to be moved between the cellars and waiting carriages.

Flats were a novelty in London at the time Albert Hall Mansions was completed. Charles Dickens (junior) writes in his 1897 Dictionary of London: ‘As for the foreign fashion of living in flats, the progress of the idea has been slow. At present almost the only separate étages to be found in London are those in the much-talked-of Queen Anne’s Mansions, a good number of sets in Victoria-street, a few in Cromwell-road, just between the railway bridges, and a single set in George-street, Edgware-road.’

By the 1870s Shaw had made the so-called Queen Anne revival style his own. It appealed to English artistic sensibilities and was adopted by Shaw when he succeeded Edward William Godwin as architect of the first garden suburb at Bedford Park, an estate occupied almost exclusively by artists (1877–9).

Ultimately, Richard Norman Shaw must be given full credit for defining the architecture for blocks of flats in a neo-Flemish style, combining picturesque romance with orderliness. It was his skill that opened the door to social acceptance of ‘the Parisian mode of life’ by an aspiring middle class in Victorian London and which was much emulated well into the Edwardian period.

[Albert Hall Mansions by Richard Norman Shaw, 1972]

Paul Latham is a director of the Regeneration Practice.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Architect.

- Architectural styles.

- British post-war mass housing.

- Classical Revival style.

- Conservation.

- Housing contribution to regeneration.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- John Cathles Hill.

- Masterplanning.

- Placemaking.

- Public space.

- Terraced houses and the public realm.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?