Flatiron Building

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

With its distinctive wedge shape, the Flatiron Building is one of the most famous historic landmarks in New York, and was one of the city’s first high-rise buildings. It was constructed between 1901 and 1903 at the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue, one of the most prominent locations in the city at the time.

The building’s name stems from the triangular plot of land known as the ‘Flat Iron’, which had been left undeveloped. Brothers Samuel and Mott Newhouse bought the property in 1899. Two years later they joined a syndicate to develop plans for building on the plot, intending it to serve as offices for major contracting firm George A. Fuller Company.

Chicago-based architect Daniel Burnham designed the building to soar directly up from street level, as opposed to the city’s new high-rise buildings that were mostly towers emerging from heavy, block-like bases. A change to New York City’s building codes in 1892 meant that steel-skeleton construction could be used, where previously masonry had been required for fireproofing.

At a height of 93m and 22 storeys, the Flatiron was not the tallest building in the city, even when it was completed in 1903, but it made a significant impression, revealing what high-rise construction was capable of achieving. Two famously dramatic photographs from Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen helped to enshrine the Flatiron as a New York icon, and it remains one of the most popular tourist attractions in the city and one of the most photographed buildings in the world.

[edit] Design and construction

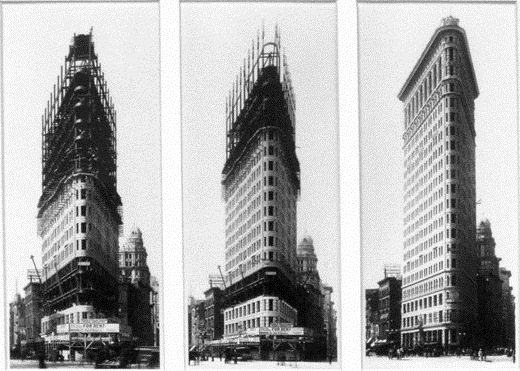

(Credited to the Library of Congress - From The Times online store, located here., Public Domain.)

Burnham’s initial design aroused a degree of scepticism regarding whether the building’s shape combined with its height would be able to withstand wind loading, and the term ‘Burnham’s folly’ entered common parlance.

Burnham used the footprint of the site to generate the base of the building, and drew from classical architecture by making it resemble a column of antiquity, becoming more slender as it moves from the base up the shaft to the capital. The building is built around a skeleton of steel, fronted with limestone and terra cotta - inspired by the French and Italian Renaissance with a Beaux Arts styling that was popular at the time as a result of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

At its narrow ‘prow’ end the building measures only 1.8m across. Viewed from above, it describes an acute angle of roughly 25-degrees.

The building was notable for its rapid rate of construction. Once the foundations were set, the floors were built at a rate of one per week. On completion of the steel frame, the rest of the building was finished in just four months. Originally 20-storeys, the penthouse on the 21st was added three years later. To access this floor, a separate elevator must be taken from the 20th floor which sits above the elevators on the 19th floor.

The building's original elevators were made by Otis and were water-powered. But they were extremely slow - it could take 10 minutes to rise from the lobby to the 20th floor. The system was also liable to flood. Today's elevator cabs feature the original interiors - a testament to their design and manufacture.

[edit] Post-completion

Although the Flatiron received a positive response from the public, architectural critics were scathing. The New York Times called it ‘a monstrosity’, and the Municipal Art Society claimed that it was ‘unfit to be in the centre of the city’.

Despite this, it was designated a New York City landmark in 1966, included on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989.

After completion, the Fuller Company moved out of the building, which was subject to much wrangling over ownership in the years that followed, not helped by the fact that the surrounding area remained quite barren. Throughout its life, the building has housed mainly publishing businesses, along with a few ground-floor shops.

In 2006, the Italian-based Michelangelo Real Estate Corporation acquired 17%, and became the majority shareholder in 2009. Their intention at the time was to convert it into a luxury hotel, although whether this happens remains to be seen. The building still houses mostly offices, including several book publishers.

The Flatiron has featured in countless postcard images and renderings, in TV shows, and in films such as ‘Bell, Book and Candle’, ‘Spider-Man’, ‘Reds’, and ‘Godzilla’ in which it is shown being destroyed by the US Army.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki:

- 7 Engineering Wonders of the world.

- Building of the week series.

- Chrysler Building.

- Citigroup Center.

- Empire State Building.

- Fox Plaza, LA.

- New York Horizon.

- One World Trade Center.

- Rockefeller Center.

- Seagram Building

- Skyscraper.

- Tallest buildings in the world.

- The history of fabric structures.

- The Oculus.

- The White House.

- Trump Tower New York.

- Unusual building design of the week.

[edit] External references

Featured articles and news

UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard V1 published

Free-to-access technical standard to enable robust proof of a decarbonising built environment.

Prostate Cancer Awareness Month

Why talking about prostate cancer matters in construction.

The Architectural Technology podcast: Where it's AT

Catch up for free, subscribe and share with your network.

The Association of Consultant Architects recap

A reintroduction and recap of ACA President; Patrick Inglis' Autumn update.

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.