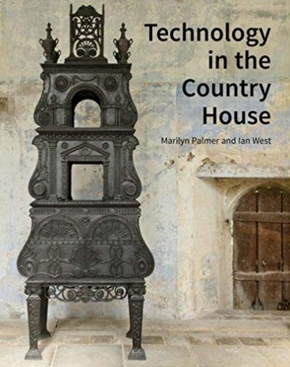

Technology in the Country House

|

| Technology in the Country House, Marilyn Palmer and Ian West, Historic England and National Trust, 2016, 205 pages, 250 illustrations. |

The technology referred to in the title includes the supply of water and sanitation, the production of energy, the preparation and storage of food, transportation systems such as lifts and railways, and the lighting, heating and ventilation of country houses. Remnants of earlier forms of technology can be found in all types of historic buildings, from cottages to mills, but the systems are rarely sufficiently intact for conservators and heritage professionals to make sense of what they have found or to evaluate their significance. However, large country estates often retain relatively intact examples because by the early 20th century most owners were struggling to maintain and update their vast rambling mansions.

Relevant technological developments are considered in the wider context of the period. For example, the chapter on lighting starts by explaining that it was not until the late 19th century that most people saw any benefit from the improvement in technology. Even then, most ordinary people went to bed at dusk and rose at dawn because artificial lighting was too expensive. The chapter goes on to consider each key development chronologically. Country house collections provide the authors with examples of sconces, candelabra and the first significant lighting improvement, the Argand oil lamp in the 1780s.

Architectural fixtures and fittings which survive are also used to illustrate the development of successive technologies, such as those of the lamp room at Castle Coole, a National Trust property near Enniskillen, where a plunge bath was used for filling the oil lamps, with a drain board above. The introduction of gas is outlined, from its first significant use in 1805 for the lighting of cotton mills, to the development of gasworks in towns and country estates. Here the legacy includes not only a variety of light fittings and related services, but also small buildings to house the retorts and purifiers for making coal gas, and the gas holders themselves.

As well as domestic technologies, the book encompasses the gardens and estates where horse power, water power and then steam engines were used to power everything from sawmills and threshing machines to water pumps. These developments are considered in terms of both the technological advances of the period and the interests and requirements of the country house owners and their advisors. Although the focus is on the technological developments rather than the sociological changes of the period, the broader perspective means that the book will fit as comfortably on the shelves of conservators as in the libraries of historians.

‘Technology in the Country House’ brings together the findings of extensive investigation and research started almost 20 years ago by the late Nigel Seeley to record all early mechanical, electrical, gas and water systems on the National Trust’s estate. Following his death in 2004, this data formed the basis for a new project with a broader scope led by Marilyn Palmer, professor of archaeology at Leicester University. With the support of English Heritage, the project expanded to include the country houses of other organisations and private estates. The result is a book which will be invaluable to everyone involved in conserving historic buildings.

This article originally appeared as ‘Systems for living’ in IHBC's Context 159 (Page 60), published in May 2019. It was written by Jonathan Taylor, editor of the Building Conservation Directory.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Architecture of the industrial revolution.

- Building services.

- Conservation.

- Energy efficiency for the National Trust.

- English Heritage.

- JW Evans silverware factory.

- IHBC articles.

- National Trust.

- Nineteenth century building types.

- Noble Ambitions: the fall and rise of the post-war country house.

- Replacing lanterns and overthrows in Great Pulteney Street.

- Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings.

- The Angel Awards.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- The redevelopment of Leicester's sewerage system by Joseph Gordon.

- The Victorian Society's top 10 endangered buildings 2019.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?