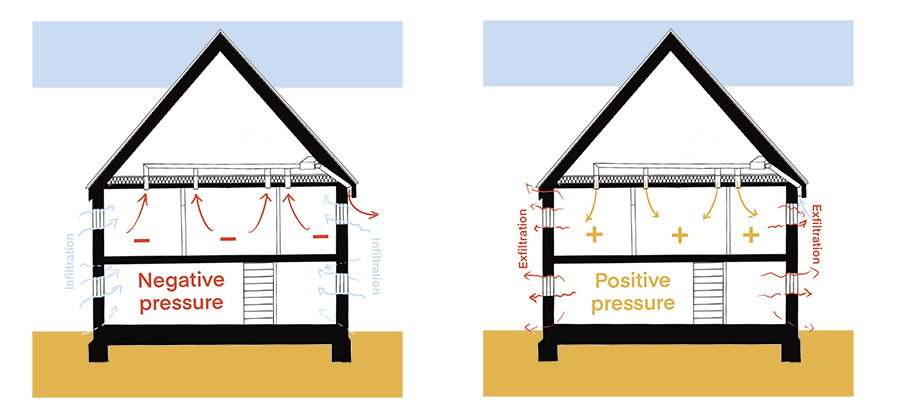

Pressurisation in buildings

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Pressurisation in buildings relates to the balance between the amount of air supplied to the building and the amount of air extracted from a building, both of which can have knock on effects on the performance of the building and its fabric.

[edit] Negative pressure

When air is mechanically extracted from a building without being mechanically replaced with supply air, the building will be under negative pressure, this will cause air to infiltrate into the building wherever it can to replace the extracted air. In certain specific cases this may be seen as beneficial in general because it causes air flow, where there might otherwise be none, which is preferable to stale air not moving. Negative pressure can pull fresh outside air into a building through the fabric, which can to a certain extent pre-heat the air. In terms of energy performance as well as general comfort however, this is not always ideal because the air is unconditioned and may be humid, and it can create drafts and cause loss of heat.

[edit] Positive pressure

When air is mechanically supplied to a building without being mechanically extracted it will cause the space to have a positive pressure, this will cause air to exfiltrate through the building fabric wherever it can, to balance the internal pressure. So a slight positive pressure can help keep hot outside air from penetrating the building during the summer, and drive stale air out through the building fabric during colder months, whilst a negative pressure during the winter will allow outside air into the building which can cause humidity.

[edit] Balanced pressure

In a low energy or passivhaus building, the building envelope should have high levels of insulation and air tightness, reducing the possibility for uncontrolled exfiltration or infiltration of air. Positive and negative pressure are not favoured as they place the high performing fabric under stress. The aim in such a building is to balance the building air pressure using Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery (MVHR) which extracts stale warm air from certain areas, and exchanges the heat with cool fresh incoming air in other parts of the building.

[edit] Mould risk

In a building that has low levels of insulation and air tightness as well as poor ventilation and in some cases heating, stale air within the building, cold spots in the fabric and drafts can cause higher levels of moisture and dampness which can lead to mould and air quality issues. Mould can form when excess moisture in the air comes into contact with cold surfaces, such as windows or poorly insulated walls. Growth of mould is likely to be worse in winter and worsened by poor ventilation and heating.

In such a scenario some arguments can be made in favour positive pressurisation to ensure fresh air is constantly supplied to a space, thus helping to drive moist air out through the poorly performing fabric. However as an approach this might be seen as a way of dealing with the symptoms of a poorly performing space rather than dealing with the root cause which is the poorly performing fabric.

In 2020 the issue of poor indoor air quality (as a result of poor ventilation and fabric performance) lead to the tragic death of a young boy in Rochdale, UK. In December 2020 a coroner ruled that a young boy died from a respiratory condition which was caused by mould in a one-bedroom flat managed organised by a housing association, the issue was discussed in Parliament and Michael Gove followed up the incident in 2022.

[edit] Air permeability testing

Approved document F, Ventilation, defines airtightness as ‘…a general descriptive term for the resistance of the building envelope to infiltration with ventilators closed. The greater the airtightness at a given pressure difference across the envelope, the lower the infiltration.’

In April 2002 the UK government introduced legislation to enforce standards of building air tightness. This was intended to lower running costs; verify the standards of materials, components and workmanship; prevent uncomfortable drafts and avoid condensation problems.

This is achieved by air permeability testing (air tightness, air infiltration or blower door testing), which measures the air leakage rate per hour per square metre of building envelope area at a test reference pressure differential across the building envelope of 50 Pascal (50 N/m2).

For more information see: Air permeability testing.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

The UK's Modern Industrial Strategy: A 10 year plan

Previous consultation criticism, current key elements and general support with some persisting reservations.

Building Safety Regulator reforms

New roles, new staff and a new fast track service pave the way for a single construction regulator.

Architectural Technologist CPDs and Communications

CIAT CPD… and how you can do it!

Cooling centres and cool spaces

Managing extreme heat in cities by directing the public to places for heat stress relief and water sources.

Winter gardens: A brief history and warm variations

Extending the season with glass in different forms and terms.

Restoring Great Yarmouth's Winter Gardens

Transforming one of the least sustainable constructions imaginable.

Construction Skills Mission Board launch sector drive

Newly formed government and industry collaboration set strategy for recruiting an additional 100,000 construction workers a year.

New Architects Code comes into effect in September 2025

ARB Architects Code of Conduct and Practice available with ongoing consultation regarding guidance.

Welsh Skills Body (Medr) launches ambitious plan

The new skills body brings together funding and regulation of tertiary education and research for the devolved nation.

Paul Gandy FCIOB announced as next CIOB President

Former Tilbury Douglas CEO takes helm.

UK Infrastructure: A 10 Year Strategy. In brief with reactions

With the National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority (NISTA).

Ebenezer Howard: inventor of the garden city. Book review.

The Grenfell Tower fire, eight years on

A time to pause and reflect as Dubai tower block fire reported just before anniversary.

Airtightness Topic Guide BSRIA TG 27/2025

Explaining the basics of airtightness, what it is, why it's important, when it's required and how it's carried out.

Construction contract awards hit lowest point of 2025

Plummeting for second consecutive month, intensifying concerns for housing and infrastructure goals.

Understanding Mental Health in the Built Environment 2025

Examining the state of mental health in construction, shedding light on levels of stress, anxiety and depression.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.