Bastles

In these fortified farmhouses of the unruly 16th-and 17th-century borders, the ground floor housed the animals while the family lived on the first floor, protected against raiders.

|

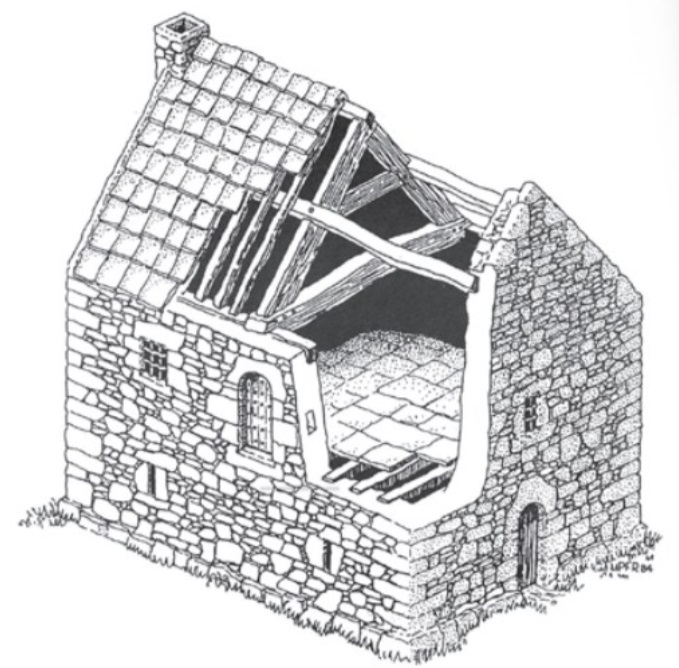

| Nine Dargue: a cutaway drawing of an Allendale bastle, showing the byre doorway as usual in a gable end, the upper door before an external stair was added, slit vents to the basement and small grilled windows to the first floor, and floor of stone slabs on transverse beams. |

A Northumberland farmer told me how he had been on the receiving end of the wrath of a transatlantic tourist. The tourist had driven miles on narrow winding roads following English Heritage signs, in this case in the remote valley of the Tarset Burn, directing him to ‘Black Middens Bastle House’. He had apparently had expectations of an edifice along the lines of Alnwick or Bamburgh Castle and was seriously underwhelmed when he eventually found something looking like a roofless barn. He did not know about bastle houses and the insight they give us into the troubled lives of ordinary border farmers. In the aftermath of the long Anglo-Scottish wars, these farmers were left far from those with either the desire or the capability of instilling any degree of law and order.

Bastles, or bastle houses, really only became public knowledge after the publication of the 1970 Royal Commission on Historical Monuments report Shielings and Bastles. This report lumped them together with the remains of the temporary summer dwellings of folk who followed their flocks to remote upland pastures. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the volume was the product of a brief, working far-from-home holiday by a small group of academics. They identified about 70 bastles, and described and illustrated them well. Then in the mid-1980s came the National Resurvey of all buildings of historic or architectural interest. This is where I got involved as a fieldworker. We rapidly realised that the Royal Commission had missed rather a lot. In Allendale, one of the first parishes surveyed, they found half a dozen bastles and we identified 40; and so it went on. Today’s bastle count must be towards 300. Although the great majority remain in Northumberland, they spread into Cumbria and also into Scotland (where they are termed pele houses).

Essentially a bastle is a small, very solidly-built house, built – and this is important – by tenant farmers, not the land-owning classes. It had metre-thick walls and the living rooms were on the first floor, above a byre in which animals could be secured behind stout oak doors. These were protected by drawbars and usually turned forts. A similar door on the first floor provided human access; originally it might have been gained by a ladder, which could be pulled up after use, but as times quietened down external stone stairs became the norm.

A handful of more superior bastles had a stone barrel vault over their byres, but the majority settled for close-set oak beams carrying a floor of stone flags, which was almost as fireproof. Bastles were designed to withstand a midnight raid, not a military siege, and one of the raiders’ prime weapons was fire. To counter this, the byre doorways of some bastles had a small opening above, a ‘quenching hole’, communicating with a first-floor recess. If the sound of crackling and smell of smoke revealed unwelcome visitors with incendiary plans, water could be poured from inside. On the upper floor might be one or two rooms, heated by end-wall fireplaces and perhaps provided with a mural recess with a slop stone, the bastle equivalent of a kitchen sink. There would be a trapdoor in the floor, so that whoever had the duty of locking the beasts in the byre – the drawbar could only be drawn from the inside – could squeeze up to join the family above. There might be a sleeping loft in the attic.

Bastle roofs rarely survive. Occasionally there might have been a stone top-vault (one survives at Snabdaugh, high on the North Tyne) but more usually either simple principal rafter trusses or upper crucks carried either stone slates or heather thatch. The latter might seem unlikely due to its perceived flammable nature, but it has been argued that historic heather roofs, unlike their modern counterparts, were kept damp and were very much ‘a peat bog on a slope’, thus posing less of a risk.

Bastles appear quite suddenly in history at about the time of the Union of the Crowns (1603), just when one might expect more peaceful conditions to become the norm. Before bastles, we know that stout timber houses were popular, as well as the traditional medieval long houses. There are a few later medieval buildings that one can see as ‘proto-bastles’, simple upper-floor houses with vaulted basements. Two good examples, both in County Durham, are Pockerley (now aggrandised to ‘Pockerley Manor’ and forming part of the North of England Open Air Museum at Beamish, although unlike the other exhibits it was always there) and Baal Hill House at Wolsingham. A few bastles are dated, usually on their door heads. Denton Foot (1594), not far south of the Wall in Cumbria, may be the earliest. Others are in the early 1600s. They seem to have been distinguished as ‘stone houses’ at the time; they were also known as ‘strong houses’ and ‘peels’. The present name, linked to the French ‘bastile’, was occasionally used as well, but only recently became generic. Most stood alone, but some formed clusters, as at Chesterwood and Wall in Tynedale, the latter which had a large green partly at least surrounded by terraces of bastles. Perhaps animals were brought onto the green at night, unless real danger threatened, when they could be secreted in the bastles. Evistones, a now-abandoned village high in Redesdale, had a mixture of bastles and long houses and Housty in Allendale, where a couple of ruined bastles survive, may have been similar.

In contrast to their appearance, bastles seem to fade out gradually. In most areas by around 1650, people were thinking it safe enough to come down and live at ground level once more, although around Alston, in the South Tyne valley on the boundary of Northumberland and Cumbria, folk lived upstairs until the later 1700s. Old maps show the town once had dozens of houses with external stairs. Many were not really defensible but the basement byres and stone slab floors persisted. Perhaps the primitive central heating provided by a byre full of warm animals underfoot remained attractive during Pennine winters.

If one wants to see a bastle, one can do no better than make the pilgrimage to Black Middens, with which this article began. A mile or two before one passes through the hamlet of Gatehouse which has several examples, and beyond the signposted Tarset Bastle Trail, the road will take you to the ruins of Shilla Hill and Boghead, which has a good quenching hole. In the Upper Coquet valley is Woodhouses dated 1602, a rather superior example (it has a basement vault and, unusually, an internal stair). The big, mullioned windows on the first floor are of 1904 and the stone flag roof of the early 1990s. Victorian drawings show it with heather thatch.

Many other examples are now houses, and of necessity have been heavily altered, sometimes only the thick walls giving them away. Others serve as farm buildings, and are more recognisable, with others simply ruins. They were usually built on a course of boulders, rather than any proper sunk foundations, and can be removed without leaving any real archaeological evidence. I remember visiting one near Bellingham, recorded as a fairly minimal ruin, in Shielings and Bastles. The last stones were in the process of being removed from the site by the farmer, a quite natural and pragmatic re-use of material. Sad but not sad, part of the continuing evolution of the northern landscape.

I will end with a tale featuring the redoubtable Frank Stoke of Chesterwood, as recounted by the guidebook writer William Weaver Tomlinson. It took place one night in the early 18th century and demonstrates something of the world in which bastle dwellers lived.

‘One winter night he was awakened by a noise, and found that someone was trying to draw back the bolt of his door with a knife. He instructed his daughter to stand quietly behind the door as the knife was withdrawn, to push the bolt quickly back again, but without alarming the party. He then took his musket, and loading it with slugs, descended through the trap-door into the cow-house below, and cautiously unbarred the door. At the top of the heavy flight of stone stairs leading to the dwelling apartment he saw four or five men with a dark lantern. After carefully surveying them for a few minutes to satisfy himself as to who they were, he broke silence in a thundering voice “You d-d treacherous rascals, I’ll make the starlight shine through some of you!” and discharged his weapon at the same moment. The holder of the lantern staggered across the stairhead, and fell headlong down the steps, shot through the heart. His terrified companions jumped over the wall and fled in all directions. Stokoe hastily entered the house, closed the door, and retired to his bed as if nothing particular had happened.’

This article originally appeared as ‘Discovering bastles’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 179, published in March 2024. It was written by Peter Ryder, a buildings archaeologist, who spent most of his life in the north east of England. In retirement in Fife, he is writing about medieval buildings and more recent nonconformist architecture.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

- Conservation.

- Cumbria's vernacular architecture and Hadrian's Wall

- Hadrian's Wall from end to end.

- Hadrian's Wall Path and the national trails.

- Heliocaminus.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Library of Celsus.

- National trails.

- Pantheon.

- What happened to Hadrian's Wall.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.