Kenneth Browne and townscape in Leicester

Analytical sketches and sketch proposals by the architect and illustrator Kenneth Browne were at the heart of Leicester’s planning and urban design in the 1960s.

|

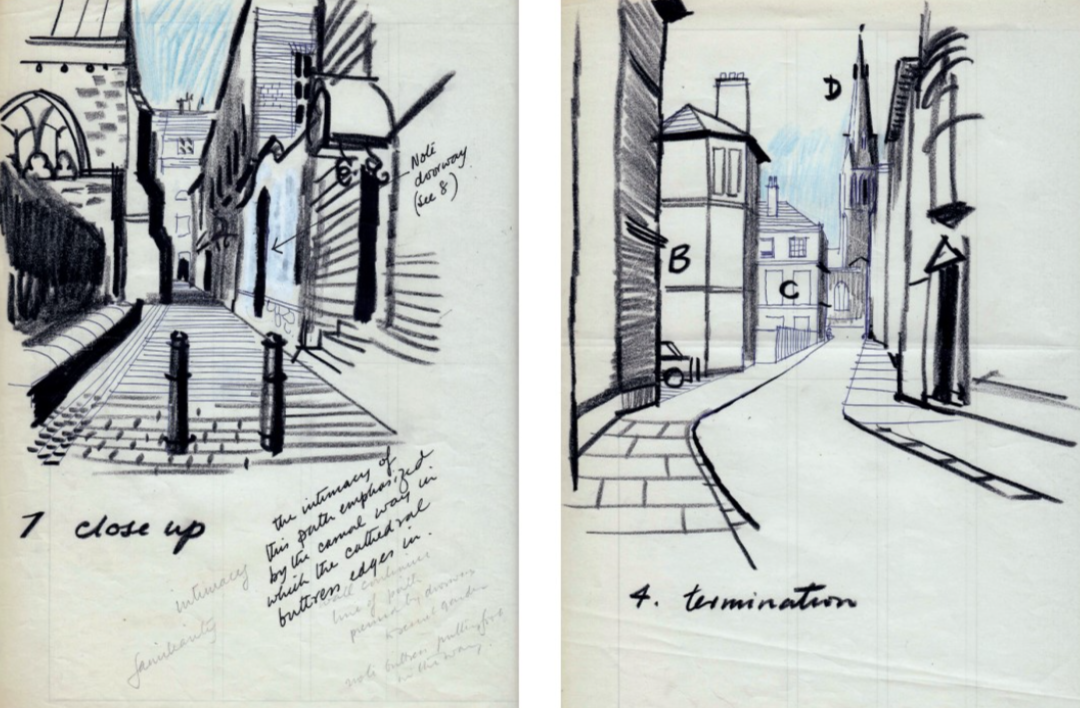

| St Martin’s East and the cathedral’s east end New Street and the cathedral tower. Reproduced by courtesy of the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland and Leicester City Council. Scans by Colin Hyde. |

Writing in the mid-1950s, WG Hoskins set out a cosy and agreeable image of Leicester, the city that had recently been his home and workplace: ‘It has a small-town homeliness… a comfortable feeling of life still revolving around ‘the old Clock Tower’ as it did in grandfather’s time… a delightful Betjeman town that one would not willingly see too much changed’ [1].

These pleasant qualities are still recognisable, but this was at best a partial picture of what was a large and thriving manufacturing city with a diverse industrial base. Even as Hoskins was writing, radical change was coming. Between 1958 and 1962 the inner ring road crashed through the western part of the Roman and medieval town, severing and partly destroying a complex historic centre that had survived the second world war largely intact.

Then in 1962 the corporation appointed the charismatic and controversial Pole Konrad Smigielski as city planning officer, only the second such appointment in the country. In the popular imagination, Smigielski is blamed for all of the real or perceived evils of the ’60s. Research by Simon Gunn of the University of Leicester [2], however, has revealed a much more complex legacy. Smigielski certainly had a modern agenda, exemplified by his plans for a high-density urban extension to the north-west of Leicester, linked to and through the city by a monorail, by redevelopment plans for parts of the city centre, and by a scientific approach to transport planning set out in the Leicester Traffic Plan [3].

But the other side of Smigielski’s vision was conservation: he designated Leicester’s first three conservation areas in 1969 and the city’s first housing general improvement area. His eventual resignation in 1972 was triggered by disagreement with councillors over a conservation issue.

Smigielski recruited talented staff, among them architects and designers. He also commissioned Kenneth Browne to provide illustrative drawings and what amounts to a townscape study, one of many carried out at the time by Browne himself and by Gordon Cullen. Kenneth Browne [4] was both an architect and an accomplished illustrator. At the time he worked in Leicester he would have been townscape editor of Architectural Review, following in Cullen’s footsteps.

Browne produced both illustrative and analytical drawings of Leicester. Some of the former were included in the Leicester Traffic Plan and blown-up prints of selected drawings were displayed in the foyer of the planning department. The Traffic Plan included a photomontage by Browne showing a monorail car gliding through the city centre. The Traffic Plan also includes a fully realised drawing of a traffic-free Gallowtree Gate, Leicester’s first experiment with pedestrian preference, pictured on a sunny spring day with more than a hint of homage to Rotterdam’s Lijnbaan.

The second set of drawings, in some ways more interesting, is the main subject of this article. It consists of 39 sketches in ball-point pen and wax crayon on quarto sheets of Architectural Review notepaper. For many years they were stored in the planning department and since 2014 they have been deposited in the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland. The set contains both analytical sketches and sketch proposals using a visual methodology and language familiar to readers of Cullen’s Townscape.

The analytical sketches focus mainly on the areas later designated as the first three conservation areas: the Castle and Jewry Wall, New Walk, and the surviving eastern part of the medieval town, including the cathedral and Guildhall, with the Georgian precinct developed on the site of the Greyfriars. The drawings are a delight, precisely observed and recorded, and annotated using familiar Cullen terminology: close up, termination, exit, secret garden and even ‘straight is the way’.

Other drawings focused on Browne’s ideas for the development of three parts of the city centre. One of these was the Market Place, where his drawings show many more tower blocks than actually appeared, looming over the 700-year old space. Browne also focused on the northern end of the 18th-century promenade of New Walk, where it meets the city centre. Browne suggested a dramatic pair of curved buildings embracing a ‘sky slit’ oriented north-south to link into the ‘big city’. The buildings would embrace a piazza with trees, a water feature and cafe tables. Smigielski’s Central Area Redevelopment Plan 1995 [5] showed a much more conventional set of tall buildings on a rectilinear plan.

Lutz Luithlen [6], who worked with Smigielski at the time, recalls that design staff were invited to prepare sketch ideas and that Luithlen’s submission, incorporating two curved buildings inspired by Toronto City Hall, was preferred. The idea was adopted by commercial developers in 1972–73 as a 13-storey and eight-storey pair of buildings, but omitting both Browne’s colourful piazza and the glazed linking building proposed by Lutz Luithlen. The space between the buildings, oriented north-east – south-west, provided no convincing visual links with the surrounding streets.

Bought off the peg by the city council in 1975, the two buildings served as the council offices for nearly 40 years before developing structural problems, leading to demolition in a spectacular controlled explosion in 2015. The subsequent redevelopment still provides an echo of Browne’s curved buildings, but this time much lower and embracing a space opening off New Walk. The gap between the buildings carries the eye westward towards the now brilliantly reimagined campus of De Montfort University.

A trace of Browne’s ideas can still be discerned in New Walk. But his ideas for the Clock Tower were even more radical and had no evident practical outcome. The Clock Tower is an architectural curiosity of 1868 built on the site of the Roman and medieval East Gate. It has survived years of critical condescension to remain the geographical and emotional centre of the city.

Browne’s play with ideas set the tower in the middle of a traffic roundabout with pedestrians circulating on a raised walkway around it. Buildings display illuminated signs in the manner of Piccadilly Circus. The tower would have a visual function but its role as the focus of a social space would be lost. Browne, of course, was working at a time when through traffic was a fact of life in all city centres. Leicester’s present pedestrian zone came together only piecemeal and over several decades up to 2007: the positive benefit from the inner ring road and its extensions.

This idea did not appear to influence Smigielski. In the Redevelopment Plan the Clock Tower, retained for sentimental reasons only, is set in a rectangular space surrounded by new buildings, including a tower block. The ensemble resembles the civic square of a new town or a borrowing from nearby Coventry.

The Kenneth Browne drawings are a treasure. Acutely observed and beautifully drawn, they are the product of a lively visual imagination. But they do illustrate the limitations and well as the possibilities of townscape as a predominantly visual concept. Since the 1960s a different idea of urban space has emerged. We now see urban spaces through the eyes of urban designers like Jan Gehl: as the stage for the countless interactions that make a city more than a collection of buildings and streets.

The context of the Clock Tower changed less radically than either Browne or Smigielski foresaw, although one side of the modern square was built in 1972 as the bulky western elevation of the Haymarket Centre. The Clock Tower now stands within the central pedestrian zone. On a December Saturday morning a band plays carols around the city’s Christmas tree, bible-wielding preachers share space with climate protestors, and teenagers wait to meet their friends as generations have done before them. It is an easy-going, engaging picture of city life. After 70 years of physical change and social transformation there is a still distant echo of WG Hoskins’ congenial vision of Leicester.

References

- WG Hoskins (1957) Leicestershire: an illustrated essay on the history of the landscape, Hodder and Stoughton, London

- Simon Gunn (2016) ‘Between Modernism and Conservation: Konrad Smigielski and the planning of post-war Leicester’ in Richard Rodger and Rebecca Madgin, Leicester: a modern history, Carnegie Publishing, Lancaster

- WK Smigielski (1964) Leicester Traffic Plan: report on traffic and urban policy, Leicester Corporation

- Sherban Cantacuzino (2009) Obituary of Kenneth Browne 1917–2009, The Guardian, 9 April

- Leicester Traffic Plan op cit

- Thanks go to Lutz Luithlen and George Wilson for sharing their recollections of working with Konrad Smigielski.

This article originally appeared in Context 167, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in March 2021. It was written by Michael Taylor, editorial coordinator for Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Conservation.

- Engineering Building, Leicester University.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- IHBC-SAHGB announce 2021 annual research award winner.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Local listing in Leicester.

- Masterplanning.

- Placemaking.

- Saffron Acres, Leicester, the UK’S largest Passivhaus residential development.

- The redevelopment of Leicester's sewerage system by Joseph Gordon.

- Town planning.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.