Johannes Kip

Three houses illustrate some typical and differing fortunes over the 300 years since they appeared in Johannes Kip’s series of engravings of Gloucestershire houses.

|

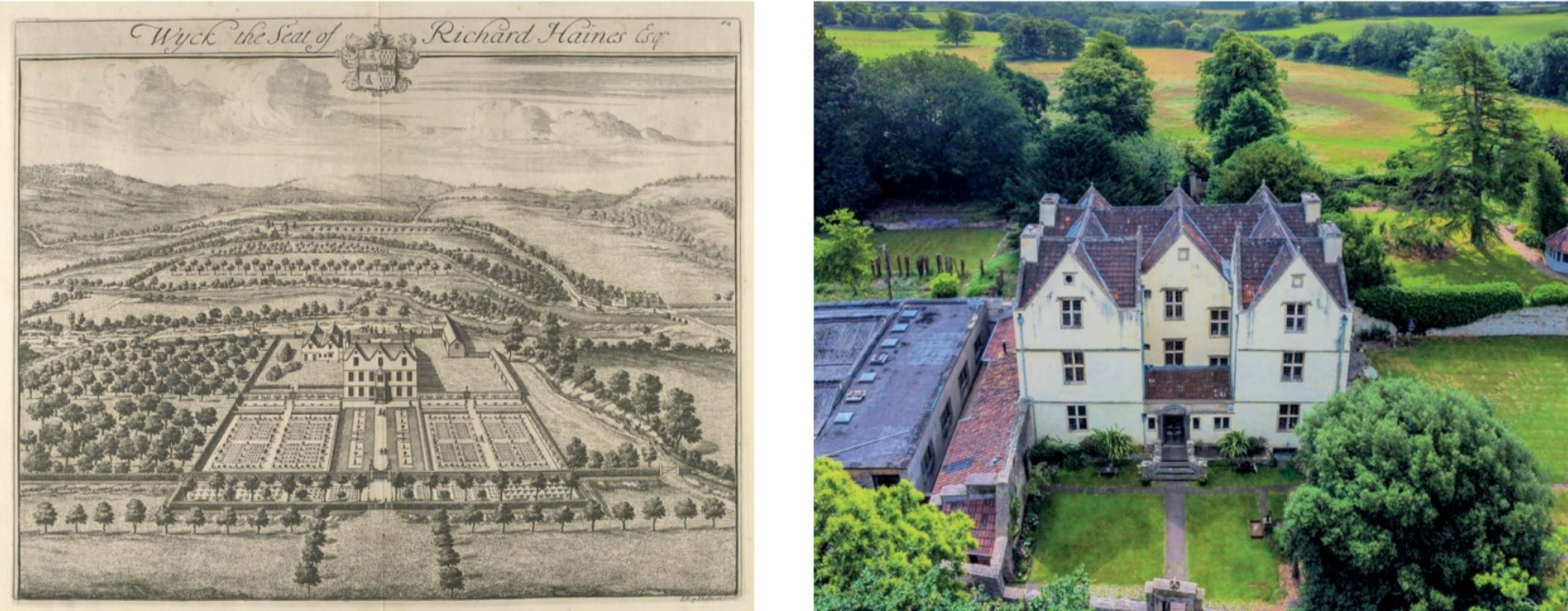

| The front of Wick Court showing the arrangement of windows to light the staircase. At the back some large trees may mark the avenue beyond the gates. (Photo: Mike Calnan) |

Johannes Kip’s engravings of 60 Gloucestershire gentry’s houses were published in 1712 in Sir Robert Atkyns’ ‘The Ancient and Present State of Glostershire’. They have been used to demonstrate the survival of all or part of a house and its garden and grounds, and to identify the likely period or periods of building, as in Nicholas Kingsley’s ‘The Country Houses of Gloucestershire’.[1] Kip’s name is known as the engraver of drawings of great country houses by his Dutch compatriot Leendert Knijff (or Leonard Kniff) in editions of Britannia Illustrata from 1707; their Badminton was included in Atkyns’ book. But Kip made the drawings of the other 59 Gloucestershire houses, as well as engraving them. The plates are placed between pages of text relating to the relevant parish (with two exceptions due to errors). It is becoming clear that Kip was an accurate draughtsman.

It possibly took five years, between 1706 and 1711, for Kip to travel around Gloucestershire in the months of better weather to visit and draw the houses for Atkyns’ book. The Berkeley Castle and Dyrham archives record owners paying for copies of Kip’s work, but Atkyns’ executors paid for the printing.[2] It is fortunate that so much was prepared before Atkyns unexpectedly died in 1711. Three houses described here illustrate some typical and differing fortunes over the 300 years since Kip visited: one hardly altered externally, one retaining part of the fabric and one with substantial additions to an important surviving building. In all cases the overall site layout remains.

Wick Court in Wick and Abson is the first house in Atkyns’ book, as the parish was then known as Abson and Wick. Externally there have been only small changes; a substantial addition since 1712 is to one side. Historic England lists the house Grade I. As with other houses of similar design, the entrance on the north front was between projecting wings; an entrance hall has since been added between the wings. Kip showed the road on this side, as it is today, with men and horses at the front gate. However, his viewpoint was the garden or south front. Here, the roof and fenestration of the porch over the garden door have also been altered since 1712. Otherwise, the six-gabled house with its elaborate roofs is immediately recognisable. It is probably early 17th century; yellow ochre plastering externally suggests that it was built by a Wynter who owned the ochre mines nearby. Sir Edward Wynter was lord of the manor in 1608, and there is an elaborate Jacobean staircase supporting an early date, with the windows on the north-west side arranged to light the stairs. In 1665 Wynter’s son sold the house to Thomas Haines, a wealthy Westbury-on-Trym grocer, alternatively suggested as the builder, by which time architectural fashions were changing; his son was the owner when Kip visited.

The boundaries and layout of the site match Kip’s engraving, and can be seen in recent aerial photographs. North of the house Kip drew a barn with typical cart entrance. The barn projects into a close possibly containing stables; an old roof is visible in the aerial photograph beyond the new building. Across the road is the River Boyd, today hardly visible through the trees. In the distance Kip portrayed the curve of the main road, and in the distance fields and low hills of what is now north-east Bristol. To the left (west) of the main house there was a hedged enclosure containing stacks of wood, and an older, smaller house, perhaps the earlier farmhouse, of which there are traces in the grass and in the wall to its rear. Beyond was an orchard, now mainly field. At the back of the house, the garden layout was formal. A central path was lined with beds containing topiary and two large yew trees still stand on each side. The path led to gates and to the vegetable garden, no longer in use, and thence to an avenue, although some large trees are possible survivors. Either side of the path were symmetrical parterres. Espalier trees lined walls, some seemingly reduced in height.

Didmarton Manor is a complete contrast, with only a small portion of the Kip house remaining, but much of the garden layout. Kip drew the east front of another early-17th-century gabled house, of two projecting wings and a central range in which the entrance was located. There was a small extension to the right (north) side. The house was probably built by Simon Codrington, who had acquired the manor in 1571 and who presented to the living in 1607; near the entrance Kip drew the small Norman church, which survives, with a wooden bellcote on the single later transept. Didmarton was added to the Badminton estate in mid-18th century and much of the house was demolished by the Duke of Beaufort in the early 19th century. Part of the front survives, with a gable, and there is a trace of the entrance doorway in the masonry. Part of the south wing also survives, but cut back to be slightly recessed behind the unaltered centre front. The south facade drawn by Kip survives as far as the garden door. There are modern additions on the north side.

Although the house has undergone drastic changes, the layout of the fairly extensive grounds to south and west are still very close to Kip’s portrayal, while simpler in detail. The owner finds traces of the path across the south lawn, which was lined with topiary in pots interspersed with taller clipped bushes. Another north/south path with fastigiate yews to one side separates the south lawn from a grand double parterre furnished with statues to the west. Today there is an enormously thick yew hedge, almost certainly survivor of the 1712 row; it can be clearly seen on the aerial photograph. Beyond the double parterre Kip drew a mature orchard where a late-Victorian church was built; happily the Norman church next to the manor house was not demolished. One ancient medlar tree possibly marks the edge of the old orchard. The line of the county boundary with Wiltshire a short distance to the south is marked with hedges and trees. Recent designs and planting echo the older layouts. Many more houses today line the village street, which remains an important highway leading from Tetbury to Bath, shown in Ogilby’s 1675 road atlas.

The third example is Leckhampton Court, listed Grade II*. Significant parts of the house are older than the other two considered here, notably the great hall on the north side of the front range, which faces west, and the battlemented two-storey porch, both considered to be 14th century. The house has the U-shape of later 16th houses. On the right (south) side of the entrance court Kip drew a close-studded, half-timbered wing, dated to the 16th century, and this also still exists, although the dove holes have gone. On the left (north) side of the courtyard, most of the range was designed by the architect RA Prothero in the late 19th century; the facade seen from the approach road appears romantic and in character with the battlemented porch. Edward VII as Prince of Wales frequently stayed here. The building at the west end of this range is 16th century, as is an extension at the rear of the central block with a doorway dated 1582. Many smaller alterations have taken place over the centuries. Sue Ryder rescued the house with very extensive restoration in 1979-81 to convert to a hospice.

The site is an interesting one. It is built into the hillside, partly on a terrace, and with Leckhampton hill rising from it to nearly 1,000 feet (274 metres); on the north the land falls away sharply. Kip drew several garden enclosures of which the layout survives but not the detail. The front courtyard appears to be grass, and had trees lining the way to the gate, but further in front there were farm buildings and a large pond, now an attractive lake; an avenue led to the church. Behind part of the south wing there was a walled garden with a variety of plants, and walls and garden survive, suggesting that this was a domestic residence. At the rear of the house there was grass, a central path from the house and side paths crossing it, and several narrow beds near a gate which still exists, but no indications of planting. To the right there are traces of the pavilion. The rising ground to the south led to a raised terrace, and beyond it an orchard; the kitchen garden has become a car park. Traces of a canal on the north side suggest that Kip was accurate in his portrayal. He obviously admired the view, as indeed did Atkyns, who mentioned the ‘large prospect’, and as do all who visit the site today.

References:

- [1] Kingsley, Nicholas (1989 and 2001) The Country Houses of Gloucestershire Volumes 1 and 2, Phillimore, Chichester

- [2] See Jones, Anthea, ed (2021) Johannes Kip: the Gloucestershire engravings (Hobnob Press) for more details

This article originally appeared as ‘Historic buildings in Johannes Kip’s engravings’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 173, published in September 2022. It was written by Anthea Jones, who was head of history and director of studies at Cheltenham Ladies’ College. Now retired, she is the author of several books on Gloucestershire history.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.