The Lost House Revisited

|

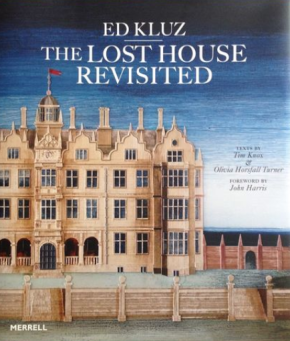

| The Lost House Revisited: Ed Kluz. Texts by Tim Knox and Olivia Horsfall Turner, foreword by John Harris, Merrell Publishers, 192 pages, 200 illustrations. |

When I worked in York many years ago, an occasional lunchtime treat was to visit the bookshop of Janette Ray, which specialised in all things architectural. It was (and is) a haven of pattern books, architectural treatises, drawings, builders’ manuals, architectural history books and prints; heaven to visit, then purgatory to leave so many fascinating items behind (they were simply outside my budget): hence the infrequent trips.

It was here that Ed Kluz was shown the catalogue of the seminal Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition ‘The Destruction of the Country House’ (1974), from which he was set on a path of representing some of these lost houses. Kluz is an artist who finds ruined and decaying buildings a source of inspiration for his work. ‘The allure of the long-gone is a powerful attraction for me, and the unseen sparks my imagination far more than the seen,’ he writes.

This book shows an impressive series of scraperboard and collaged images of nine lost country houses, including some of the most mourned – Holdenby House, Coleshill, Fonthill Abbey and Eaton Hall among others. Some were deliberately slighted or demolished when the ambition of the original buildings became too much for the families to sustain. Others were lost to fire. The houses are presented in stark landscapes, stripped of the visual clutter of real life, held in a magical moment. The effect is akin to a Tudor portrait, dramatic lighting illuminating one great character who demands our attention. They command the stage while they deliver their soliloquy, holding us entranced as we enter their dream-like state. Kluz recognises his theatrical inspirations, having had a passage from The Tempest pinned to his studio wall while creating these works.

An additional and unexpected pleasure of the book is Kluz’s eloquent essay about historic buildings, explaining his fascination with them. He writes of preferring a building in decline or decay as more dynamic and romantic than an inhabited and well-maintained one. On visiting Clandon Park, the day after the fire, he explains: ‘The scorched ruin of Clandon was one of the most horrifying and yet thrilling sights that I have witnessed. To see a house rapidly slip out of existence as it is destroyed by fire, blown up by dynamite or smashed by a wrecking ball is to observe perhaps the most perfect end to an extraordinary life – almost as if the curtain falls on a centuries-long performance.’

In his scraperboard images of the houses on fire, it is not just the historic fabric going up in flames, one can feel the emotions and experiences, the laughter and music, the hopes and fears that the buildings housed, that had become embedded in the fabric, perishing too. It reminds us that it is not just the architecture that is unique to every building but something more fragile still that defines each: its atmosphere.

The book has an informative introduction by Tim Knox, who places Kluz in the tradition of country house illustrators from Kip and Knyff engravings, through 18th and 19th century artists to John Piper and Julian Barrow in the 20th century. Each of the illustrated houses is given a short and incisive biography by Olivia Horsfall Turner that puts flesh on the bones of the buildings. It’s a minor point, but I would have preferred Kluz’s pictures to be in one section, with the biographies in a second, so as not to distract. At either end of the book is a small selection of Kluz’s other work, which left me hoping for another much more comprehensive tome on his art (please).

As an artist, Kluz offers a different perspective on the decay and demolition of historic buildings. ‘The unexpected cutting short of the life of a building is a stark reminder that death and slow decay come to things both living and inanimate,’ he writes. One of the shortest and quietest sentences in the book is perhaps the most thought-provoking: ‘Maybe it’s fine to let things go.’

This article originally appeared in IHBC’s Context 154, published in May 2018. It was written by Kate Judge, a freelance architectural historian.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.