Brazilian Modernism

|

| Brazilian National Congress, Brasilia, architect Oscar Niemeyer, completed 1958. |

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Modernism in Brazil is not considered a ‘style’ by the country’s cognoscenti, more a reworking of European themes that were modified, even transformed, by incorporating the multi-racial and multi-cultural roots of the country. But having been treated to an erudite presentation by Alan Higgott at Docomomo, it is difficult to consider Brazilian modernism as anything but a style.

[edit] Not a style?

Impressive though it is, whether in the slick,1960s Corbusian manifestations of Oscar Niemeyer or the later, sometimes crude Brutalism of Bo Bardi, Brazilian modern architecture slots very easily into the stylistic precepts of ‘Modernism’.

But that does not detract from the architecture one bit. Much of it can hold its own against Europe’s very best – which is not surprising: Le Corbusier, Bo Bardi (an Italian) and others from Europe had a huge influence on post-war Brazilian architecture.

Where do you start with Brazilian modernism but with Brasilia itself – the capital city. Planned by Lucio Costa, the area resembled a desert (like Las Vegas in that respect) and was conceived as a practical utopia (unlike Las Vegas) with Oscar Niemeyer designing hundreds of buildings for the city. Even today, many appear impressive and one can only imagine the effect they must have had on people in the 1960s.

Even with Brasilia’s windswept plazas, Niemeyer’s juxtapositions of straight and curvilinear forms provide endless vistas of stunning formal contrasts. But he could also be frivolous and irrational, as seen in the parabolic concrete shells of his expressionistic church of San Francisco at Pampulha (1943) with its inverted square tower. He described it as “functional, beautiful and shocking” and was a departure from the ‘reason’ that so dominated the Modern Movement in Europe and America.

Slides of Niemeyer’s casino at Pampulha reveal the same mannerisms and playfulness in a building that is a celebration of Corbusian forms, particularly the pilotis and ramps rising through space. But it also demonstrates Niemeyer’s maxim that “pure functionalism is not enough”.

Niemeyer formed part of the team (with Le Corbusier as consultant) that designed the stunning Ministry of Health and Education (1943) in Rio, a building that would not look out of place in Marseilles.

Elsewhere, the Water tower at Olinda (architect Luis Nunes, 1937) – more a Miesian flat-slab skyscraper than a water container – is notable for its complete domination of the colonial surroundings. Monumental in appearance, it is the sort of building that would have turned many in Europe against modern architecture. But according to Higgott, Brazil did not experience – for whatever reason – an equivalent anti-modernist reaction.

[edit] Artigas and Bo Baldi

Other architects on Higgott’s whistle-stop tour included JV Artigas and his brutalist and monumental Faculty of Architecture and Planning, University of Sao Paulo (1961-1969); and numerous Lina Bo Bardi works – most notably, her Museum of Art in Sao Paulo (1957-68) with its 70m-long pre-stressed concrete beams and expansive internal spaces.

But it was her most brutal work, SESC Pompeia (1982) with its bold, rectilinear, raw concrete towers linked by multi-level walkways that drew gasps from the audience – whether it was the monumentality, the raw concrete brutalism or the free-form Fred Flintstone-style windows that made more of an impact, it is hard to say.

Higgott proved himself a fluent, relaxed authority on the subject and it was not long into the lecture that it became apparent that his detailed knowledge was not only of the buildings presented, but of Brazil’s modern art and architecture generally. This is not surprising as he has visited the country and many of the buildings presented on several occasions over the years. Given the architecture and the locations, can anyone blame him?

The lecture ‘Brazilian Modernism’ was given by Andrew Higgott, architectural writer and historian, at Docomomo, London, on February 26, 2019. Further details about Docomomo can be found here.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki.

Featured articles and news

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.

The 2025 draft NPPF in brief with indicative responses

Local verses National and suitable verses sustainable: Consultation open for just over one week.

Increased vigilance on VAT Domestic Reverse Charge

HMRC bearing down with increasing force on construction consultant says.

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

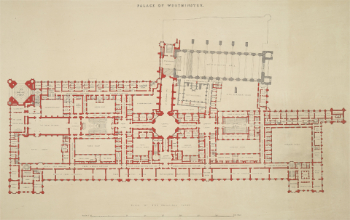

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

Comments

Looks like an apartment block ...