Sharing local authority conservation services

|

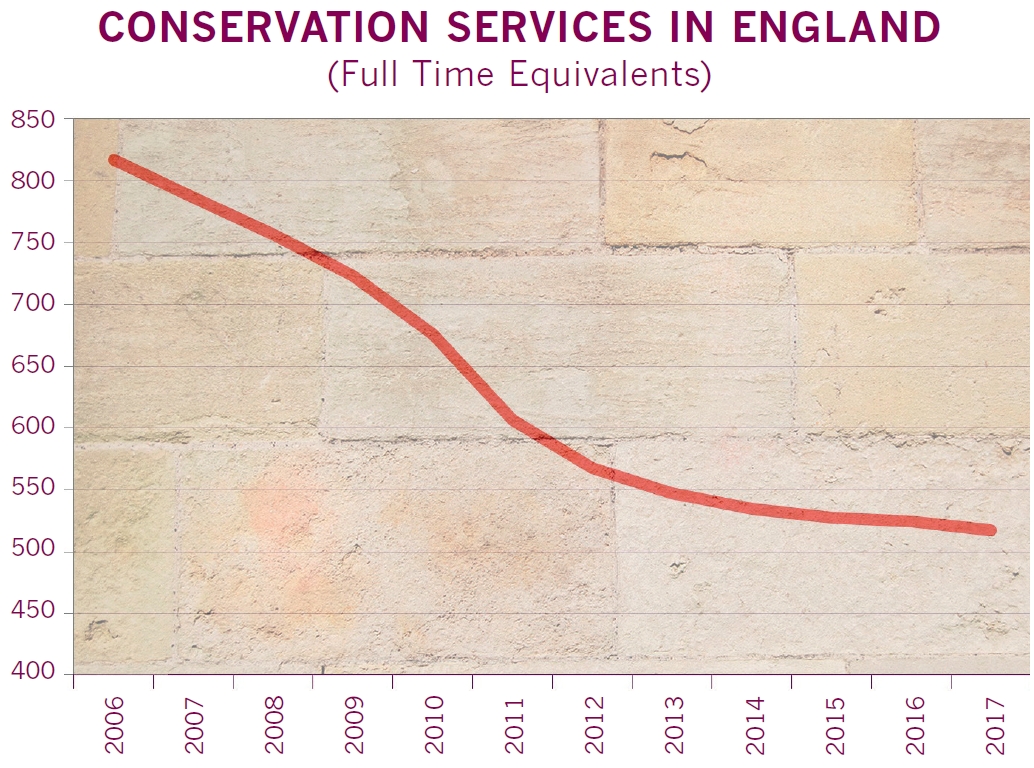

| Local authority conservation capacity in England, 2006–17 (see Further Information, HE/ALGAO/IHBC, 2017). |

The Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) longstanding work in collecting and analysing information on conservation provision across the UK is well recognised. The collection of data in Northern Ireland this year will complete at least initial baselines in the whole of the UK following the ongoing work in England since 2006 and one-off studies of Wales and Scotland.

The IHBC research in England, funded and published by Historic England, shows that local authority conservation services have experienced more than a decade of cuts. In 2017 conservation capacity was reduced by a further 0.5 per cent with a cumulative decline of 36 per cent since 2006.

Set against the backdrop of overall service reduction, the changes have been specifically in the loss of in-house specialist staff. The provision of staffing bought from other local authorities has remained fairly static from 2006, when it made up 1.2 per cent of all local authority capacity, to a current level of 1.3 per cent. Likewise there has been a slight increase in the use of consultants carrying out the equivalent work of an in-house officer. Today around 2.3 per cent of total conservation capacity is provided by a consultant in this role, while in 2006 it was 1.2 per cent.

The decline of local authority conservation capacity has led not only to a cutback in services in general but also in the specifics of their work. A narrow focus on development management has replaced previously more widespread and proactive roles in policy making, regeneration through conservation, strategic work in historic areas and positively tackling heritage at risk. Similarly, training, knowledge transfer and outreach aimed at property owners and other members of the public, and as part of succession planning for service staff, have also been curtailed.

But even the resources available for the mainstream management of development have been hit. Illustrating the picture of continued rising workload and decreasing resources, the number of application decisions continues to increase (planning decisions by 3.6% and listed building consent decisions by 0.62% in the last year). Demands on existing capacity are already stretched and will only increase with time.

Effecting a major reversal in local authority practice is outside the institute’s influence but the IHBC still works in partnership with other like-minded professional and sector bodies to advocate for conservation services, while also offering training and guidance.

Mapping the long decline of conservation services is not the IHBC’s only contribution to maintaining local authority conservation services. With the baseline data in place to help it understand the capacity and types of conservation service at work today, the institute is well placed to work on projects and initiatives to support and recognise local authority services.

Conservation services remain diverse in their structures but radical changes to these structures have often accompanied the staffing decline. Cuts, reorganisations and redundancies have led to many conservation teams being reduced to a single post, often not full time, and with a growing risk that staff will lack formal training in conservation. The loss of senior and experienced staff before any replacement, or indeed without replacement, reduces continuity of knowledge and practice. Increasingly non-specialist staff are being seconded to conservation posts, at least six per cent of current services include staff without formal training or longstanding experience. These changes may all lead to impacts on the breadth of work the service is able to handle and the quality of advice given.

The majority of conservation services still operate from and within the planning service. But conservation officers are now increasingly based in development management with its more direct links to casework, either through direct advice or as actual case officers. When monitoring of conservation services first began in 2006 there were more standalone conservation or environment teams, but those smaller one- or two-person services were frequently based in planning policy where they were often one step removed from the decision process as consultees. Some reorganisations placed the conservation service away from its traditional home within the planning function and into a central corporate department. However, this trend now appears to be diminishing as it becomes apparent that while it may offer advantages for corporate working it can weaken the working links within the planning process.

In recent years shared services have been seen by some as a way forward for maintaining local authority working in the new world of reduced budgets and reduced capacity. Examples of shared service include the provision of specialist advice by one authority with specialist conservation staff selling its services to another. There are also a number of examples of joint posts where two or more separate councils work together to develop shared staffing and jointly recruit to a post or posts. Some shared services are created when local authorities are merged or create a formal alliance. These joint structures may simply merge back-office functions but where they create a fully merged staff structure, that may then include conservation. A final model for sharing involves establishing a separate company or charitable body to provide specialist conservation advice, usually by existing staff from the member authorities being transferred into the new organisation.

Shared services are not a panacea for loss of capacity and the early closure of some relatively new shared services may be a sign that the tide is turning on this way of working. In some cases sharing can protect existing conservation services for the future or offer conservation services to authorities that would not otherwise have them, but such arrangements can also be vehicles for reducing capacity, losing skilled staff and decreasing the scope of work carried out. While some shared conservation services carry out duties that represent the full spectrum of conservation specialist advice, most do not take on work outside the most mainstream development management advice. The exclusion of crucial activities from the service may meet the basic statutory needs of dealing with applications but it may not provide the level of conservation service that is truly necessary.

If a local authority does not have access to appropriate specialist advice then decisions cannot be properly informed and the authority’s statutory and corporate responsibilities addressed. The IHBC continues to collect information and consider where local authorities are currently maintaining an appropriate level of informed conservation specialist advice and how this advice is being obtained.

Further Information:

- Analysis of the Impact of Sharing Local Conservation Services, IHBC, 2015 http://bc-url.com/sharing-services

- The Ninth Report on Local Authority Staff Resources, HE/ ALGAO/IHBC, 2017 http://bc-url.com/LA-staff-resources

This article originally appeared as ‘Sharing capacity, Local authority conservation services’ in IHBC's 2018 Yearbook (Page 35), published by Cathedral Communications. It was written by Fiona Newton, operations@ihbc.org.uk.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Charging for Listed Building Consent pre-application advice.

- Conservation officer.

- Conservation officers in historic towns.

- Conservation practice survey 2016.

- Conservation.

- Heritage asset.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Impact of heritage sector local authority funding cuts in south west England.

- Local authority conservation specialists jobs market 2014.

- Loss of senior conservation staff and posts in England March 2010 to April 2011.

- Planning authority duty to provide specialist conservation advice.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?