Thermal comfort and wellbeing

The thermal comfort of an occupant can affect his or her wellbeing in a number of ways. This article will go through some of these, following on from a description of thermal comfort and how it can be quantified.

The thermal comfort of a person is described as 'that condition of mind that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment and is assessed by subjective evaluation'. CIBSE comfort guide states the main aim is 'to keep most of the people happy most of the time' (Race G.)

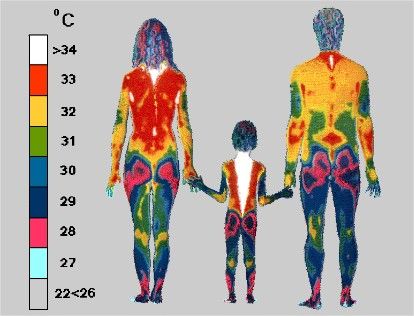

The thermal comfort of an individual is personal and varies greatly from person to person and gender.

The subjective evaluation usually suggests a survey is needed to get the personal input from each of the occupants of a building. The large range of conditions and number of people required to give proper averages make this impractical in the majority of cases and cannot be done pre-occupation.

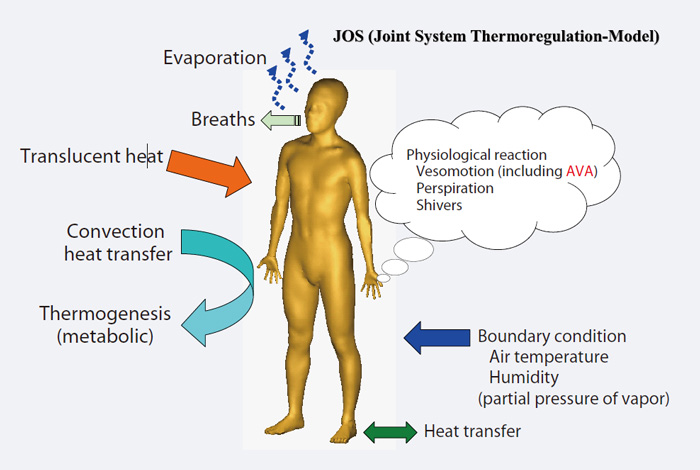

A different approach consists of measuring environmental conditions and then calculating the thermal comfort indices, which relate to the measured values and calculated indices as if a range of people were surveyed.

The standards BS EN ISO 7730 and ASHRAE 55 give methods for taking the environmental measurements and subsequent calculations to give quantified numbers to compare thermal comfort between buildings and different conditions within the same building. The measured values required by the standard are; air speed, turbulence intensity (using the standard deviation of air speed), air temperature, black globe temperature/operative temperature and relative humidity.

The thermal comfort calculations provide values for the Draught risk, Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) and the Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied (PPD):

- The Draught risk is an indication of the percentage of people that would perceive a draught given the measured conditions and uses air temperature, air speed and turbulence intensity.

- The PMV is a prediction of the average vote of a large group of people occupying the space as if a survey was conducted on a scale of -3 to +3; where '-3' indicates feeling cold, '+3' indicates feeling hot and '0' is comfortable.

- The PPD is an estimate of the percentage of people who would find the space uncomfortable, based on the PMV results.

The calculations of PMV and PPD take into consideration the insulation provided by clothing (CLO) and the activity of the people working/living in the space (MET).

The CLO is a measure of the average clothing insulation and the MET is a measure of the heat output from an average person doing a stated task in the space. The standards give methods to calculate the CLO and MET for a space, however, the actual individual values can change drastically depending on the occupiers of the space, e.g. an office space versus a supermarket or factory floor where the activity level is significantly different, therefore the specific CLO and MET must be chosen carefully to give true indicative values of PMV and PPD.

One thing to note is that the PPD has a calculated minimum of 5%, as for the CLO and MET there will always be some people who will feel either hot or cold, however, this is normally compensated by changing an individual’s CLO, i.e. if a person is in an office and wearing a jacket, and the dress code allows, they will remove it when feeling hot, etc.

The effect on wellbeing of thermal comfort is becoming a focus of study and is coming to the attention of building owners and occupiers. The reason for the focus is that detrimental thermal comfort can have a significant effect on the morale and in some cases even the mental and physical health of the occupants of any building.

Problems with morale or health can affect productivity. A measurement of the thermal comfort, either pre-occupation by heat-load testing or of the occupied building, can identify problems or show that the building conforms with the expected comfort levels required, e.g. the BS EN ISO 7730 standard has classifications of the space depending on the PMV, PPD and other factors.

The distraction caused by adverse thermal comfort can be significant and can lead to occupants feeling the space is uncomfortable even if the conditions in the space improve, e.g. either through changes to the ventilation system, or by moving an individual to a more suitable thermal environment. If a space is felt to be too hot or too cold for too long and no actions are taken, the perception of the occupants can become biased. Perceived long term thermal discomfort can be hard to dispel and productivity can be negatively affected.

This article was originally published here by BSRIA in Jan 2017. It was written by Calum Maclean, Senior Research Engineer, BSRIA Sustainable Construction Group, but has subsequently been edited by others. See the article history for more information.

--BSRIA

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- A Practical Guide to Building Thermal Modelling.

- BREEAM Thermal comfort.

- BSRIA articles on Designing Buildings Wiki.

- Building related illness.

- Heat stress.

- Human comfort in buildings.

- Indoor air quality.

- Maximum and minimum workplace temperatures.

- Measuring the wellbeing benefits of interior materials.

- Overheating in homes – BSRIA residential network event.

- Sick building syndrome.

- Temperature in buildings.

- The Flourish Model to enhance wellbeing.

- Thermal comfort in buildings.

- Thermal environment.

- Wellbeing.

- Wellbeing considerations for property managers.

- What we know about wellbeing.

Featured articles and news

The Architectural Technology podcast: Where it's AT

Catch up for free, subscribe and share with your network.

The Association of Consultant Architects recap

A reintroduction and recap of ACA President; Patrick Inglis' Autumn update.

The Home Energy Model and its wrappers

From SAP to HEM, EPC for MEES and FHS assessment wrappers.

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.

Demonstrating that apprenticeships work for business, people and Scotland’s economy.

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.