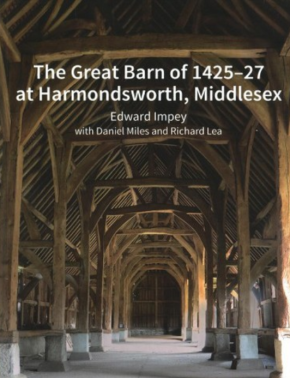

The Great Barn of 1425-27 at Harmondsworth, Middlesex

|

| The Great Barn of 1425-27 at Harmondsworth, Middlesex, by Edward Impey with Daniel Miles and Richard Lea, Historic England, 2017, 89 pages, 31 colour and black and white illustrations, paperback. |

It is sadly ironic that half a century ago the late Ian Nairn contrasted the architectural majesty of the great barn at Harmondsworth with the mediocrity of the neighbouring aircraft hangers a short distance away at Heathrow (Nairn’s London, Penguin Books, 1966). Soon, if the proposed northern runway at the airport goes ahead, the setting of this medieval masterpiece will be irrevocably destroyed, together with the total removal of one conservation area and the decimation of another.

It is perhaps too much to hope that wiser counsels will prevail following the publication of this meticulously researched book. In the language of the National Planning Policy Framework, the barn is a building of the highest national significance, and in accordance with Conservation Principles the book is a major contribution to our understanding not only of this fine example but also of the purpose and function of large medieval barns in general.

Firmly dated to 1425–27 both by dendrochronology and documentary evidence, it was built for William of Wykeham’s Winchester College, which had purchased the estate in 1392. The assembly of former monastic estates to provide an endowment for Wykeham’s complementary foundations of Winchester and New College, Oxford, is described in the opening sections, followed by a detailed discussion of the motivation and possible cost of building the Harmondsworth barn. A minute structural analysis of every element of the fabric is concluded with an instructive exposition on how the details of the carpentry can be used to speculate on the sequence of erection of the timber frame. The argument is clearly illuminated by a staged series of 24 three-dimensional diagrams in full colour.

A lengthy exploration of the function of the barn is based on extensive documentation, embracing changes in agricultural practice on the manor, the yields and harvesting of the various crops and their processing, and the officials and labour involved throughout the farming year. The context for the barn and its enormous size is provided by comparison with other medieval barns, with tables listing basic details of the 19 largest barns in England, and the 12 largest barns in France and Flanders. Although this section ranges across much of southern and midlands England and across the channel in northern Europe, it would have been helpful to have looked at some other surviving examples built for pre-Reformation institutions closer to Harmondsworth in the Greater London area.

These might have included the great barn on another Winchester manor of Ruislip, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s barn close by at Headstone, which provides clear evidence in its fabric for the farming of the demesne, and the Hall barn at Upminster, Essex, owned by Waltham Abbey and with similar vertical boarding to the cladding at Harmondsworth.

The manor of Harmondsworth passed out of monastic tenure in 1543. The subsequent ownership is traced until the barn ceased to be used for agricultural purposes in 1986 and was bought by a building company. Some repairs were carried out before the company fell into receivership and after a lengthy period of uncertainty English Heritage took the brave decision to purchase it ‘for the nation’ in 2011. Under its responsible stewardship the barn was fully restored in 2014 and is now open for public access for the first time in 500 years.

It was a remarkable initiative and I would urge everyone to support it by making a pilgrimage to enjoy what John Betjeman described as one of the ‘noblest medieval barns in the whole of England’ before the tranquillity of its setting is shattered by the noise of jet engines. There they will be able to see the quality of the craftsmanship of the original fabric and the sensitive restoration. Armed with the scholarship in this definitive book they will be able to appreciate why it was built and how it has functioned throughout its long history. It is an exemplary study of the design and architectural significance of a great medieval building and is highly recommended.

This article originally appeared as ‘The noblest in England’ in IHBC’s Context 154, published in May 2018. It was written by Malcolm Airs, Kellogg College, Oxford.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?