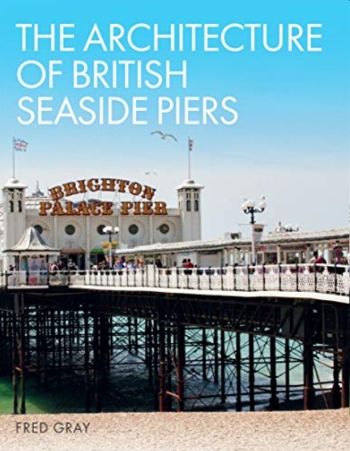

The Architecture of British Seaside Piers

|

| The Architecture of British Seaside Piers, Fred Gray, Crowood Press, 2020, 197 colour and 123 black and white illustrations, hardback. |

Piers are structures that define the British seaside. Derived from stone breakwaters and jetties, the first piers gave early 19th-century visitors, who came to seaside towns to enjoy the purity of the sea air and drink seawater for its medicinal qualities, another way to consume nature: it allowed them to walk on water. Ryde, Brighton and Herne Bay were among the earliest piers built on timber piles with timber decks.

In the second half of the century, with the growth of railways, the seaside became accessible to the masses. Between 1860 and 1901, 77 new piers were built in these newly popular towns. Timber was largely replaced by a mixture of cast and wrought iron, as structures became increasingly daring and long, accommodating a range of buildings offering entertainment. They proved hugely popular: when Blackpool pier was completed in 1863, 20,000 people attended the opening, whereas the population of the town was only four thousand.

But there is an inherent problem with piers: with their feet in salt water and being buffeted by waves, they are high maintenance and expensive to keep. Timber decays, iron rusts and the sea itself can destroy in a single storm. The 20th century saw the decline of many piers. Some suffered during the second world war: Southend, Plymouth Hoe and Margate were bombed, and Brighton West, Clacton and Eastbourne were damaged in explosions of drifting mines.

After the war, piers suffered economically as commercial flights took visitors away from British seaside towns. While the towns quietly stagnated, piers actively decayed. The inevitable started to happen. Cowes pier was dismantled in 1961. When Morecombe pier was wrecked by a storm in 1977, it was demolished, as were Hunstanton and Herne Bay. Many succumbed to fire, most famously, Eugenius Birch’s masterpiece, West Brighton Pier, in 2003.

One great success story, though, is Clevedon Pier, which John Betjeman thought was ‘the most beautiful pier in England’. Following the partial collapse of its wrought-iron structure in 1970, a building preservation trust was formed and, drawing on funding from English Heritage and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the pier was fully repaired. Revived in the original form of a walkway over water, the pier is exquisitely elegant.

An unexpected new audience has been brought to the pier too: with One Direction filming their video You and I there, it has become the Abbey Road to a new generation. I am guessing, though, that the author of this book, Fred Gray, does not have a teenage daughter, because in this fact-filled book, full of interesting old photos and drawings and displaying a clear understanding of the technology of piers, the One Direction effect on the popularity of Clevedon is not mentioned.

This article originally appeared as ‘In a seaward direction’ in Context 168, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in June 2021. It was written by Kate Judge, architectural historian.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Coastal defences.

- Conservation.

- Conserving Cornish harbours.

- England's seaside heritage from the air.

- Future of seaside towns.

- Heritage coast.

- IHBC articles.

- Jetty.

- Lighthouse.

- Pier.

- Seashaken Houses: A lighthouse history from Eddystone to Fastnet.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Waterfronts Revisited: European ports in a historic and global perspective.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?