Regularly and diligently

Most construction contracts set a date by which the works must be completed. This is either by means of a defined completion date, or a commencement date and a specified period for the works. If no date or period is defined, a term will be implied that the contractor must complete the works in a reasonable time (that is the time it would ordinarily take, plus an allowance for any extraordinary circumstances).

The completion date is not the date by which all obligations under the contract have to be discharged, but the date by which 'practical completion' must be certified. That is, the date by which the works have been completed and the employer can take possession of the site, albeit there may be very minor items outstanding that do not affect beneficial occupancy by the employer. If practical completion is not certified by the most recently agreed completion date, then the contractor may be liable to pay liquidated and ascertained damages to the employer.

However, unless the contract includes other express provisions requiring that the works are carried out in a particular way, the contractor can achieve the completion date, by, for example, starting slowly and then speeding up, or by working sporadically. There is no implied term requiring that the works are carried out to a specific timetable (see Leander Construction v Mulalley 2012). This can cause problems for the employer, both in terms of being reassured during the course of the works that the completion date will be achieved, and in programming their cash flow so that payments can be made.

Some contracts may provide for sectional completion, setting different completion dates for different sections of the works. This is common on large projects, allowing the client to take possession of completed parts whilst construction continues on others. Other contracts (such as NEC3) define key dates that the contractor must achieve during the progress of the works.

However, many contracts, such as the JCT standard form of contract require that the contractor proceeds ‘regularly and diligently’ with the works, irrespective of whether they are likely to achieve the completion date. They cannot for example work sporadically, or slow down if it becomes apparent that they will beat the completion date. If they fail to proceed ‘regularly and diligently’ with the works, the contract administrator may issue a written warning notice, and if they continue to default, the contract administrator may give notice determining the employment of the contractor. The employer may also be able to claim damages if they can demonstrate that they have suffered a loss.

In the case of West Faulkner Associates v London Borough of Newham, the Court of Appeal held that the term ‘regularly and diligently’ meant that:

“…the obligation upon the contractor is essentially to proceed continuously, industriously and efficiently with appropriate physical resources so as to progress the works steadily towards completion substantially in accordance with the contract requirements as to time, sequence and quality of work.”

The contractor's master programme is not part of the contract documents, and is not enforceable under all forms of contract, however, failure by the contractor to meet the dates on the contractor’s master programme might be evidence that they are not proceeding regularly and diligently.

Sub-contracts may include similar obligations, and for example, JCT subcontracts require sub-contractor progress to be reasonably in accordance with the progress of the main contract.

Clearly, care must be taken when exercising rights under these clauses. Construction contracts do include provisions for dealing with delays, and not all delays will be due to the fault of the contractor:

- Extensions of time allow the completion date to be moved due to causes that are not the contractor’s fault, although the contractor is required to prevent or mitigate the delay and any resulting loss, even where the fault is not their own.

- If the completion date is missed, the employer can claim liquidated damages.

- There may be situations in which it is in the employers’ interests to suspend the works temporarily.

Notes.

- The term ‘Time is of the essence’ refers to a contractual position in which if one of the parties to the contract fails to complete their obligations by a specified date, then the other party can treat the contract as terminated. This is not generally applicable to construction contracts unless there is an express term.

- The phrase ‘time at large’ describes the situation where there is no date for completion, or where the date for completion has become invalid. The contractor is then no longer bound by the obligation to complete the works by a certain date. They may however still be bound by an obligation to proceed regularly and diligently or to complete the works within a reasonable time.

- On NEC contracts both parties must give early warning of anything that may delay the works, or increase costs. They should then hold an early warning meeting to discuss how to avoid or mitigate impacts on the project.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

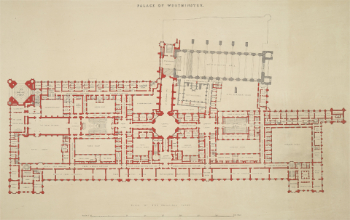

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this.

Comments

Could you expand on what 'regularly and diligently' can practically mean, with examples? Where have cases been decided where it's borderline.

For example, I have a home extension project that has gone from the initial 3 months of consistent 20-30 person-days of labour per week, to the current series of weeks of 5, 1, 7, 0.5, 0, 10 and then 2 person-days per week. Not regular in my book, but I suspect the builder is trying to do the absolute minimum they can do to not be in breach of contract.