Mid-rise urban living

Mid-Rise Urban Living, Chris Johnson, Lund Humphries, 2021, 128 pages, 41 black-and-white illustrations and 32 colour plates.

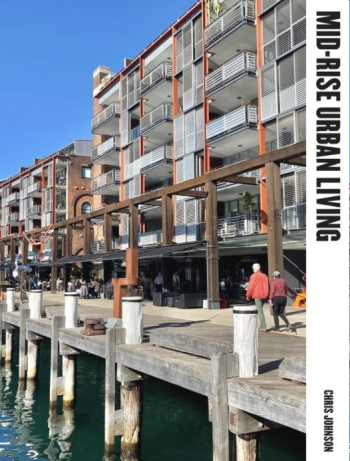

Chris Johnson is a former government architect for New South Wales and CEO of Urban Taskforce Australia. He lives the mid-rise dream in an apartment ‘on the edge of Sydney’s wonderful harbour’. The author ranges widely in search of examples but his conclusions appear to be strongly influenced by his Australian experience.

Johnson defines ‘mid-rise’ as housing of five to six storeys, although some of his examples are higher. This he says is ‘the missing middle’. Observers of British cities, on the other hand, may see midrise as the mushrooming middle. In terms of historical precedents, Johnson starts at Kowloon and follows a fairly well-travelled route through Haussmann’s Paris, the Barcelona of Cerdà and Gaudí, Georgian-to-20th-century London and on, via Berlage’s Amsterdam, to Jane Jacobs’ New York.

Johnson does not discount other urban forms, from tower blocks to low-density suburbs, but he favours mid-rise for inner cities and city centres. Historical precedents are again cited from Siena and Rome, and Johnson draws on the ideas of urbanists from Camillo Sitte to Jan Gehl. Mid-rise can give clear definition to street edges and can provide the density of population necessary to provide active thoroughfares and public spaces. It can fulfil environmental requirements, and can incorporate mixed uses and active frontages.

The author draws on contemporary case studies to demonstrate his ideas of good practice from Singapore, the Netherlands, Boston (USA), London and Australia. Examples from India show that mid-rise can provide low-cost housing. Johnson illustrates examples of handsome affordable housing in Sydney.

In the last chapter, the author examines the political and economic barriers to mid-rise, and the perceived rigidity of planning systems and design codes. Curiously ‘third-party appeals’ are listed (by the Prince’s Foundation) among the obstacles to mid-rise in London. Johnson quotes London architect Peter Barber’s call for planning to favour ‘a socially and ecologically sustainable urbanism structured by idealism rather than net-twitch neurosis’. The author argues for mid-rise along transport corridors and advocates diversity in design (planning is again seen as the problem here). The book illustrates a range of contemporary built examples from around the world, ranging from urbane, through showy to bizarre.

Much of Johnson’s agenda is good urbanism. Mid-rise can provide a population to support the economy of city centres and inner cities. This is happening around the UK, and is historically well-established in cities such as Edinburgh, Glasgow and London. From our conservation point of view mid-rise can, as Johnson shows, provide new uses of historic buildings and suitably scaled contextual development for historic areas.

But the book is not without flaws. Cars are seen in some of the pictures in the book, but there is little discussion of the impact of parking or traffic generation. An example of a ‘mid-rise villa’ in Germany has blank ground and first floors, presumably used for parking, hardly providing the active frontages and neighbourly qualities that Johnson advocates.

More seriously, the book is too reliant on architectural determinism. The success of housing depends on tenure, management, cost to the occupier, energy costs, social and cultural factors and many other considerations. Johnson offers a beguiling picture of his own neighbourhood beside Sydney harbour with its friendly ground-floor coffee shops and restaurants, and shared gym and swimming pool. But those benefits are not an automatic consequence of built form. They accrue to people who have choice and who can afford to live at a prime location in an expensive city.

This article originally appeared as ‘The mushrooming middle’ in Context 170, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in December 2021. It was written by Michael Taylor, editorial co-ordinator for Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?