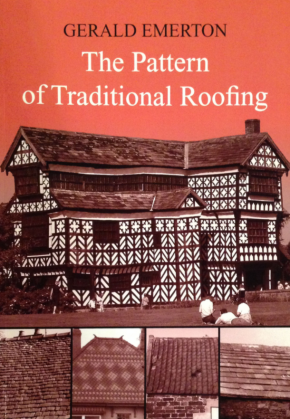

The Pattern of Traditional Roofing

The Pattern of Traditional Roofing, Gerald Emerton, privately printed, 2018, 352 pages, 379 colour and black and white illustrations and line drawings, softback, from Glebe House, Acton, Nantwich CW5 8LE

Gerald Emerton is a fourth-generation slater and tiler based in the north west of England, whose sons and grandsons continue the business today. The author of ‘The Pattern of Scottish Roofing’, published by Historic Scotland, he has brought his wealth of experience and knowledge to the subject of vernacular roofing across England and Wales. The book is structured around the materials used and their regional particularities, with historical accounts gained from documentary sources, company records and historic manuals.

The first section describes the various gritstone and sandstone slates which are found almost exclusively in the localities where they were quarried, including the Pennines, West Yorkshire, East Cheshire, the Lancashire Moors, the Cumbrian Fells and the Welsh Marches. A section follows on the limestone beds suitable for roofing. These are found mostly in a belt stretching from Sherbourne at the southern end to Cirencester to the north. The roofs made of small, thick stone slates found in Cotswold villages are among the most beautiful in Britain, but require exceptional skill to lay.

The chapter on natural slates covers Westmorland green slates, the Welsh quarries and a small outcrop in the Charnwood Forest area known as Swithland slates. Plentiful slate quarries were widely spread across Wales and served their local communities, but the huge quarries of Bangor, Caernarvon and Blaenau Ffestiniog led to the opposite result in the 19th century, being delivered by rail and sea to all parts of the country. Emerton focuses on the small quarries, almost all of which have now been closed down, regretting the fact that the big industrial quarries are incapable of producing consignments of random slates and thus have limited relevance for heritage slating work.

While the author claims it was not his intention to produce a training manual, each chapter contains passages on roofing techniques. One describes the creation of slated valleys, which have always been a complex issue for both carpenter and slater, and of which there are many different methods (all naturally without the use of cement mortar). Another covers the means by which quarrymen calculate the quantity of slates required to cover a random slate roof, and the subsequent sorting and setting out of the material by the slater to ensure a successful result.

The final section deals with clay roof tiles. As with slates, these can be distinguished by their geological characteristics. The different clays used determine their colour and texture, and their sizes and forms differed across the country. The author’s photographs are a major feature of the book. They show the diversity of roofing slates and tiles, the methods of setting out, the design traditions and the detailed treatment of eaves, valleys and hips across the country. Looking at these, it is clear how present-day barn conversions and re-roofing of vernacular buildings with machine-made tiles, each an exact image of its neighbour, bland in colour, with sawn-cut verges and half-round ridges have harmed the rural scene. These, he ironically observes, display the desire of many of our decisionmakers, including those conscious of our built heritage, to ‘admire a neatly-laid, hand-made pantile roof with detailed finishes which do not offend the appearance of the limitations of the past’.

In comparison with brick and stone, the art of roofing has received limited attention, and this makes Emerton’s book an invaluable tool for all conservation professionals. It is also a salutary reminder of the distinctive traditions that continue to be eroded by the loss of craftsmanship and understanding.

This article originally appeared as ‘Laddertop view’ in Context 165, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in August 2020. It was written by Peter de Figueiredo, reviews editor of Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?